Last month, Florida took its latest step in its long redistricting saga. On September 12th, oral arguments were held before the Florida Supreme Court over the state’s Congressional map; specifically the elimination of the black-performing 5th Congressional district. The arguments, held before a 6-1 conservative court, gave way to not only worries that precedent would not be adhered to, such precedent supports bringing back the old 5th, but that the court may strike down the state’s anti-gerrymandering rules all together.

For this 200th issue of my substack, a newsletter that has covered redistricting extensively, I want to bring things up to speed on Florida’s sordid redistricting drama.

Have you done the readings?

There is absolutely no way I can go over every detail of Florida’s 2022 Congressional redistricting drama in this post. The “lore” here is deep: from 1990s redistricting fights, to redistricting reform passed at the ballot box, to Florida Supreme Court precedents. I am going to hit some key points, but below I am providing links to the many articles I have written on the topic of Florida redistricting.

My Florida Redistricting History Series - This is a ten article series I wrote in 2021 that covered the history of gerrymandering and apportionment in Florida from statehood to present day. I detailed the history of the Pork Chop Gang, the cracking of Black voters under Democratic rule, and the packing of Black voters under Republican rule. I covered the 2010 passage of Fair Districts and critical Florida Supreme Court precedent that DeSantis now hopes the modern court will overturn.

My Florida Redistricting Tour - This series of articles looked at potential redistricting maps in the fall of 2021. It began before the first draft maps came out and reaction to the initial drafts. These articles largely focused on State Legislative lines, rather than Congressional.

My substack redistricting issues - I have written several issues covering the 2021-2022 redistricting process in Florida. These articles track my reactions to initial legislative drafts, the original DeSantis proposals, the fight within the legislature, and DeSantis eventually getting his way. It also tracks the map challenges in the courts.

Through this article, I will reference different issue numbers from the above you can go to for more information. Think of them like citations.

In total, including this article you are reading right now, I have written right around ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND words on Florida redistricting since 2021. I will now try to take all that and cram into a succinct summary. God help me.

Background Heading into 2021 Redistricting

I believe the best way to make summarize this long saga is to explain where redistricting precedent stood heading into 2021. Republicans controlled the legislature and hence the redistricting process. However, the passage of Fair Districts Amendments in 2010, along with Supreme Court cases in 2012 and 2015, left many right-wing lawmakers eager to avoid a major fight.

The 2010 Fair Districts Amendments set up expanded protections for minority voters AND set up official bans of partisan gerrymandering. It laid out two tiers for redistricting; with Tier 1 taking precedent. I cover all the details on these measures and the campaign to pass them in Issue 6 of my Redistricting History series.

Tier 1 – Lines cannot be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or party. Districts also cannot be drawn to diminish the ability of racial or language minorities to elect candidates of their choosing. Districts must be made up of contiguous territory.

Tier 2 – Districts must be compact, as equal in population as possible, and honor administrative boundaries when possible.

These measures passed with 63% of the vote. They were a response to the 2002 gerrymanders by Florida republicans, who drew non-compact districts designed to pack Black voters as much as possible while also splitting up other Democratic communities. The Fair Districts measures aimed to end the partisan gerrymandering and over-packing of Black voters while also ensuring minority districts were protected. Districts were expected to follow geographic and political boundaries where possible to create compact seats; but said compactness could be sacrificed for ensuring racial representation.

Lawmakers passed a Congressional plan in 2012 that was less gerrymandered than the 2002 plan. However, it still had several issues and a challenge to the districts went through the courts. After the discovery process revealed GOP efforts to get around Fair Districts, the Florida Supreme Court struck down the state’s 2012 Congressional map (Issue 8 of the history series). Many precedents were set there, but the big issue here concerns North Florida. The map on the right show the 2012 map from the GOP legislature; with the map on the left being what came out of the 2015 ruling and subsequent debate. In terms of racial representation, the most critical change was the court striking down the 5th district, the dark blue snake going from Jacksonville to Orlando, and instead ordered lawmakers to consider a Jacksonville to Tallahassee proposal, as that would be more compact.

In the 2012 redistricting process, GOP lawmakers argued the packing of Black voters all the way down to Orlando was needed to ensure Black voters controlled the seat. As such they had a district 49% Black Voting-Age Population (and majority-black overall).

The Fair Districts Amendments, as interpreted by the Florida Supreme Court in 2012 (read History series Issue 7), lay out that there is no magic census number needed for a district to be a “Black performing seat.” The court relied on the precedent of “Functional Analysis” - which means to take the political implications of a district into account. This has been a longstanding practice in Florida. To sum up how it might work

A district is 40% Black via census data. However, because it is historically a very Democratic district and the Democratic primary is 65% Black, it is a functionally-Black seat.

A district is 55% Hispanic. However, due to registration rates being lower as well as voter turnout, only 30% of the general election voters are Hispanic. On top of this, neither party primary is over 25% Hispanic. This is not a functionally Hispanic seat.

In the 2015 redistricting process, the Florida Supreme Court directly sited that a district could be drawn from Jacksonville to Tallahassee that was more geographically compact than the snake-like 5th while also performing for Black voters. That new 5th was less Black via the census but still majority-black in the Democratic primary; which was the key fight for a 60%+ Democratic seat. Al Lawson would go on to win that district and hold it through the rest of the decade.

As a result of this change in North Florida, the new 10th in Orlando was a Black-access seat thanks to being solidly democratic and right around 50% Black in a Democratic primary. Val Demings would win this seat, leaving Florida with four Black-performing districts for the first time. Per the Fair Districts Amendments, these districts were protected from “retrogression” - meaning their elimination. Baring demographic changes, the legislature was bound to not reduce the number of Black-performing seats. Therefore, it was believed the 5th, certainty, would be safe in the 2021 and 2022 redistricting process.

The 2021-2022 Redistricting Drama

Heading into the 2021 redistricting season, Florida had a tremendous amount of precedent and laws that would limit how much gerrymandering could be gotten away with. While the Florida Supreme Court has since become more conservative, it was still believed GOP lawmakers would be eager to avoid court fights and stick with precedent. Conservatives activists were eager for the legislature to strike down the 5th and maximize Republican gains via redistricting. However, while it was possible the legislature would try and gerrymander the Congressional lines around Tampa or Orlando, they’d be unlikely to risk court anger by touching North Florida.

The initial redistricting drafts confirmed this to be the case. My initial coverage of the State Senate’s Congressional plan (Issue 18) and the State House’s Congressional plan (Issue 22) showed both intendent to keep the 5th district intact. I railed against the House plan for its clear gerrymandering efforts in Orlando - but as I figured - North Florida remained largely the same. The district, all all version, was not majority-Black, but it retained its Black-performance because it would be over 70% Black in the all-important Democratic Primary.

Through 2021, the legislature made changes and amendments to plans, but the basics remained the same. It seemed to the big debate in the legislature was over Orlando. Senators felt that the Black-performing 10th had protections, while the House did not. As I documented then, the 10th had undergone demographic changes that had diluted Black shares of the vote; though a primary would still likely be plurality Black. No one debated the 5th, however. Everyone agreed it was protected. The State Senate would eventually pass this plan. There plan also retained the 10th as a Black-access seat as much as possible.

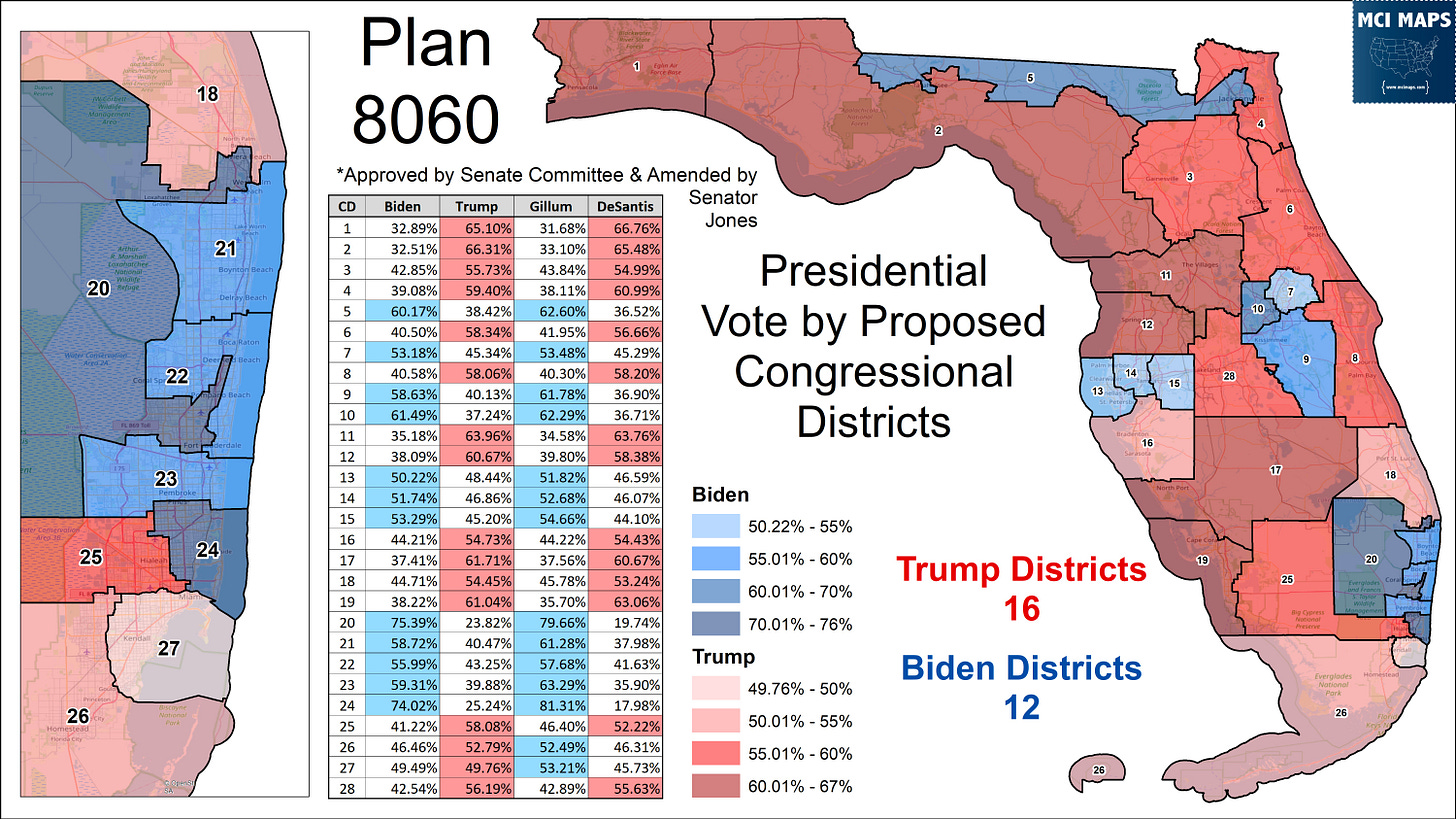

Then, on Martin Luther King Day weekend, DeSantis released his first proposal for a map; one that was an extreme GOP gerrymander (Issue 29). It removed the 5th district and carved up the North Florida Black population across several districts. Three different plans were presented by the DeSantis team, with the final map that passed being seen here.

I must sum up a great deal of political back and forth that took place in the Spring of 2022. Lawmakers initially balked at any plan to carve up the North Florida 5th (Issue 34). DeSantis argued the east-west 5th violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. Applied to redistricting, this prevents districts from being drawn to only take race into account. A Florida example can be seen from 1992. The original court-drawn North Florida black seat, then numbered the 3rd, was eventually struck down for violating equal protection.

That district was designed to give Black voters a voice, but it also took nothing but race into account; ignoring all other redistricting principles. It was struck down in 1996 BUT the mandate for a Black seat did not go away. That is how we ended up with the still-snake-like but more compact 5th and then the even more compact Tallahassee-Jacksonville 5th. I actually did an entire special issue on the saga of redistricting in North Florida. You can see that below.

DeSantis argued the Tallahassee-Jacksonville 5th the legislature drew was akin the the 1992 district; an insane claim. The draft 5th, per lawmaker defenses, kept several counties whole while also using major roads and communities in how it divided Tallahassee and Jacksonville. The district united the two cities, but it also linked up rural Black voters that traced their ancestry to slavery and sharecropping.

“He wanted to change it because he didn’t want an African American to represent this area where slave owners, sharecroppers lived, from Jackson County all the way down to Duval County. They stayed in those areas and were not represented until I got there.” (Al Lawson talking about why DeSantis aimed to get rid of the 5th)

DeSantis asked the Supreme Court to rule on the matter, but the court refused until a final map was passed. Lawmakers passed an alternative plan (Issue 39) that offered up two proposals - one keeping the Tallahassee-Jacksonville 5th, or a plan that would create a black-opportunity seat in just Jacksonville. That Jacksonville-only seat would have been Biden +13 and over 60% Black in a Democratic primary (Issue 36).

DeSantis VETOED that proposal (Issue 41) and eventually the legislature caved and passed his plan (Issue 44) in a special session that ended in a sit-in by several Black lawmakers (Issue 46). By all accounts, and I document this in my coverage, DeSantis threatened the lawmakers with budget vetoes and primary challenges if they did not go with his plan.

Initial Court Strike-Down

An instant lawsuit was filed to stop use of the map in 2022. In May, Leon County Circuit Court Judge Layne Smith struck down the Congressional plan! I delved into the full ruling in Issue 49. The initial suit was entirely revolving around the 5th, basically seeking an injunction on North Florida. It would not preclude an expanded lawsuit to come.

In the ruling, Judge Smith agreed with plaintiffs that eliminating the 5th, which had performed for Black voters before, the state had violated the Fair Districts rules against retrogression. This was based specifically on Fair Districts rules, NOT the Voting Rights Act. The VRA would come into play if a majority-Black district could be drawn. However, Fair Districts has an expanded version of this retrogression principle. If a district is performing for a minority group, as the 5th was, then it is protected. I delve into the legal precedent much more in past issues; with plenty of case citations.

As expected, the state appealed the decision. Most worried, including myself, that the timeline was too short; with primaries coming in August. Indeed an appeal led to a stay of the ruling; meaning 2022 would for sure go ahead under the DeSantis plan. That November, Congressman Al Lawson would run in the 2nd district, losing to Neal Dunn. For the first time since the 1980s, no Black congressperson represented North Florida (Issue 100). The lawsuit over the Congressional plan continued under the case Black Voters Matter vs Byrd.

In June of 2023, the plaintiffs suing had a big piece of good news in the Alabama redistricting case, Allen v Milligan. In that case, the US Supreme Court upheld Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and ordered the state to draw a 2nd black-performing Congressional district. I delved into the specifics in Issue 114, but relevance here was the US Supreme Court affirming that racial representation mandates are still alive and well. A major part of the DeSantis defense in the lawsuit was that Fair District’s rules against retrogression were federally unconstitutional. While this case did not affirm Fair District’s expanded standards, which are broader than Section 2 of the VRA - they key item for Alabama’s case, it was the court siding with racial group concerns in redistricting.

Stipulation Agreement & Trial Court Victory

Shortly after the Alabama ruling, a major development emerged in the Florida redistricting case. By the summer of 2023, everyone was ramping up for an August trial. The plaintiffs suing were arguing against lines in North Florida, Tampa, and Orlando. The suit broadly argued the plan was a political gerrymander ordered by Ron DeSantis. Then in early August, the plaintiffs and state agreed to a major stipulation agreement, which radically limited the scope of the case.

I delve into every detail in Issue 123, so I am going to sum up this briefly. The plaintiffs basically agreed to limit the entire case to North Florida. No longer would the trial be about DeSantis meddling or the gerrymandering issues in Tampa or Orlando. As I covered in my issue, the plaintiffs likely saw that North Florida was the best chance with a much more conservative Florida Supreme Court.

In the agreement, the state admitted that the elimination of the 5th was a violation of Fair Districts. The state admitted that racially polarized voting in North Florida means that Black voters have a protection under Fair Districts, and as such a Duval-only seat is not an acceptable alternative. The state’s defense would be entirely on the issue of if the 5th could withstand federal scrutiny of equal protection. The state agreed that if it lost the case, the Exhibit 2 map offered by plaintiffs would be an acceptable alternative (though it wouldn’t have to be used). The proposed remedy is below.

The agreement also stipulated that the loser of the case would agreed to appeal directly to the Florida Supreme Court to ensure a new map could be implemented for 2024.

On August 24th, both sides held oral arguments with Florida Second Judicial Circuit Judge J. Lee Marsh, a Rick Scott appointee. I documented the oral arguments extensively in Issue 125, but the long story short was the state struggled greatly at defending its positions. I will sum up some key points below but #125 delves into much more.

Plaintiffs argued that the 5th district as proposed, while long, fit many redistricting principles. It kept many counties whole and only 2% of its lines did not follow major roads or county lines. Plaintiffs argued the district was race conscious; basically it aimed to be compact but did take race into consideration, something that is allowed. This is an except from my issue at the time.

A key point of the plaintiff case was that race CAN be part of a redistricting map. Race predominance, which we saw with many 1990s districts, is a problem because of how unclear district borders are. Those districts have no true identity beyond race. However, race consciousness has been legally acceptable for decades. This was even highlighted in the recent Alabama redistricting case, which saw the US Supreme Court order the state to draw a 2nd black-performing district. Race can be a factor, especially in regions where racist sentiment is historic and still remains.

For North Florida, this idea of racial consciousness clearly applies. The mutual agreement both sides laid out a few weeks ago even admits to the issues with racial polarization in North Florida. Granted, it seemed the state went back on that admittance, as their court briefs saw them claim North Florida did not have discriminatory sentiment.

Because of North Florida’s racially polarized voting, drawing districts to ensure Black representation is allowed. Currently several county commission and legislative districts take race into consideration. What is not allowed is race predominance, which that original 3rd district from 1992 is a good example of.

Despite the state agreeing about racially polarized voting in the stipulation agreement, the defense team tried to argue the opposite in its filings with the judge. I delve into this more in my writings from the time, but there were actually two defenses. One defense was the legislature, the other was the Secretary of State, who basically represented the DeSantis administration. Considering Secretary of State Cord Byrd is a far-right former state representative, it should be no shock that the filings from the SOS was filled with claims that Black voters in North Florida deserved no protections.

This argument did not hold up well with Judge Marsh. On September 2nd, Judge Marsh sided with the plaintiffs and struck down the state’s Congressional map for North Florida. Judge Marsh stood by Supreme Court precedent that had established the east-west 5th back in 2015. Marsh wrote that North Florida’s history of discrimination and continued racially-polarized voting warranted such a district and that its elimination in 2022 violated the Fair Districts rules against retrogression, or non-diminishment. I delve into the legal specifics in Issue 126, which covers the ruling.

With Marsh’s ruling, the stipulation agreement meant that the state, which pledged to appeal, would try got do so right to the Florida Supreme Court. Both sides submitted briefs acting the appeals court to pass the appeals right onto the top court. However, the appeals court refused! The appeals justices insisted on hearing the case, throwing the planned calendar of appeals and new maps into jeopardy.

Appeals Court Insanity

After Judge Marsh’s ruling, it looked very likely that the east-west 5th would eventually be restored. Even the conservative Florida Supreme Court could come in an simply affirm the ruling. It also could have relied on a portion of Marsh’s ruling that state the State itself has no authority to litigate if a district violated equal protections. Basically, if someone wanted to argue a district was a pure racial gerrymander (like the 1992 version of the 3rd), a voter would have to bring that case.

Everything got flipped upside down through when the appeals court demanded to hear the case. The appeals bench, stacked with hyper-conservative justices, held oral argument on October 31st, arguments that showed the justices were hostile to the issue of racial representation. Then at the beginning of December, the appeals court ruled in favor of the state of Florida, overruling Judge Marsh.

The ruling, which I covered extensively in Issue 141, is a completely batshit insane ruling. The court rejects much of the data in the stipulation agreement; questioning the common bonds of Black voters in North Florida. It also claims that previous Florida Supreme Court rulings on Fair Districts were not precedent setting; and hence not something the court needed to consider. The court also argued that the 2015 version of the 5th is not a valid benchmark and was an illegitimated district. The justices effectively agreed with the Byrd/DeSantis position that the 5th only connected Black voters with no real ties together and was hence a racial gerrymander. Now my writings and even some short points here talk about how the North Florida black community does share a common heritage and unity.

However, another aggravating thing was the hypocrisy of focusing on the 5th district as some sort of extreme racial gerrymander. If DeSantis and Byrd were consistent in their redistricting principles, then a district like the Florida 20th would never be in the current map. The 20th is a majority-Black seat that connects the Black voters of Palm Beach County and Broward County. As you can see below, its lines are heavily influence by race.

Voters here are connected through the empty Everglades. It is literally impossible to walk from the Broward to Palm portion of the district while always being in a populated census block. And to be clear, I am 100% good with this district. This seat units two Black communities to give them a unified chance at electing a candidate of their choice. I am A-ok with this!

This seat, because it can be majority-Black, is protected by the VRA as well as Fair Districts. Originally the DeSantis plans did not keep a district like this, instead aiming for a Broward-only seat. However, when the veto and the special session were agreed to, lawmakers convinced DeSantis to adopt their version of South Florida; likely realizing changing the 20th would be a slam dunk court loss.

If the 20th can be accepted as sacrificing compactness for racial representation, then there is no reason the old 5th cannot be as well. Both take race into consideration, but neither are like the old 3rd. THAT should be the difference between a legal racial consideration and illegal racial gerrymander. So when DeSantis and Byrd say they have a “race neutral map” - I am telling you they are full of shit.

The appeals court ruling was a hack opinion that you need to read issue 141 to truly appreciate. It not only rejected the 5th, but it also aimed to severely weaken the anti-retrogression standards of Fair Districts. Their logic is hard to summarize here so I implore you to read my issue on that topic. It is a ruling that if left intact would not overturn Fair Districts, but seriously gut its racial protections for a litany of seats.

The result was a major delay in the redistricting timeline. It allowed the Florida Supreme Court to take its sweet time agreeing to hear the case, meaning 2024 goes ahead under the old map. So how do things look with the Florida Supreme Court

Supreme Court Oral Arguments

Through my coverage of the redistricting saga, I have been fully aware and acknowledged that the current Florida Supreme Court is much more conservative than the 2012 and 2015 court that wrote so many of the current precedents. I’ve talked about the shifting nature of the court twice

Thanks to the mandatory retirement ages for Florida justices, a court that was once 5-2 liberal is now 6-1 conservative. The litany of Chiles and Crist appointments have been replaced with Scott and DeSantis picks. In my opinion, that is why the plaintiffs wanted the stipulation agreement so that the case could focus on the most egregious act, the elimination of a Black-performing seat in North Florida. As I stated at the time, if Fair Districts cannot protect North Florida Black voters, its not worth the paper its printed on.

Oral arguments for this case were heard in September. The proceedings were not as bad as the oral arguments before the appeals court were, but the justices did show their conservative leaning. They did reject some of the more extreme appeals court decisions, but notably questioned about the “constraint” anti-retrogression standards had on future map makers. An excellent documenting of different arguments made by the Justices and attorneys can be seen in reporter Jacob Ogles twitter thread. The oral arguments definitely do not make me optimistic about a positive ruling, as the Justices displayed a solid lack of care for the concern of Black voters in North Florida. That said, oral arguments are not always a predictor, and lots of research and lobbying takes place in the meantime. I am obviously nervous that the Supreme Court either rejects the argument to bring back the 5th, or outright disseminates Fair Districts altogether. There is also a possibility the court looks for an “out” and basically orders a bigger fact-finding trial renounces the stipulation agreement. There is no clear timeline on a ruling.

The worst case scenario at this point is the complete destruction of Fair Districts. In a true legal sense, there is no valid reason to do this. However, the Florida Court has demonstrated plenty of hackery in recent years. In previous election cycles the court did not allow Marijuana legalization to go on the ballot; arguing language was misleading on flimsy grounds. The court has also allowed the state to add language to the pro-choice ballot measure this year that says it might mean abortions will be paid for by the state (it won’t). This court, by and large, can make whatever precedent ruling it wants.

Looking Ahead

Regardless of the court outcome, whether its a destruction of Fair Districts or a miraculous ruling for the defendants, I am already looking ahead. This process has already revealed that an independent redistricting commission is sorely needed. I argued this point WAY back in 2016, amid the redraws happening at that time. The process is subject to political games and an increasingly conservative court system. The Congressional map is gerrymandered in multiple places, but here we are hoping for a positive ruling on just the most extreme example. Tampa and Orlando are left in the shadows.

I have screamed about this issue for years. Expressed my frustration that for all the cash thrown at different ballot measures, no major players have stepped up to fund such an effort. It will be expensive, no doubt about it. However, this saga must reveal how broken this process is.

Once we get past this election, and assuming the Orange fascist has not been elected, my focus is going to turn heavily towards this redistricting issue. Of course, all I can do is make the case. Without money or manpower, we are going to be subjected to gerrymandered maps from now on. Some folks need to step up.