Issue #13: The Shifting Politics of FL's Supreme Court Elections

As the court moves to the right, retention elections change

This week I want to talk about Florida’s Supreme Court. This seven-member body has long been a thorn in the side of the Republicans who’ve run the state for the last twenty years. Until recently, the top court in Florida was ruled by a liberal majority; thanks to a coalition of Lawton Chiles and Charlie Crist appointees. This court was responsible for striking down GOP laws, removing conservative measures from the ballot, and forcing redistricting special sessions for Congress and State Senate. The court was such a bogyman for the right that 2010-2012 House Speaker Dean Cannon tried to push measures to weaken the court. These “reforms” pushed by Conservatives never went anywhere. Instead, focus moved to the retention election of justices.

Lets talk about these

Judicial Retention Elections in FL

In Florida, Supreme Court judges go before the voters in retention elections. Voters can vote to retain or reject the justice. At no point in Florida has the retention of a justice failed.

These retention elections are almost always quiet affairs. Justices don’t normally campaign or even acknowledge the vote. They can’t ask for money, though they can open campaign accounts to take donations. Often no money is needed or raised. Retention happens, we move on.

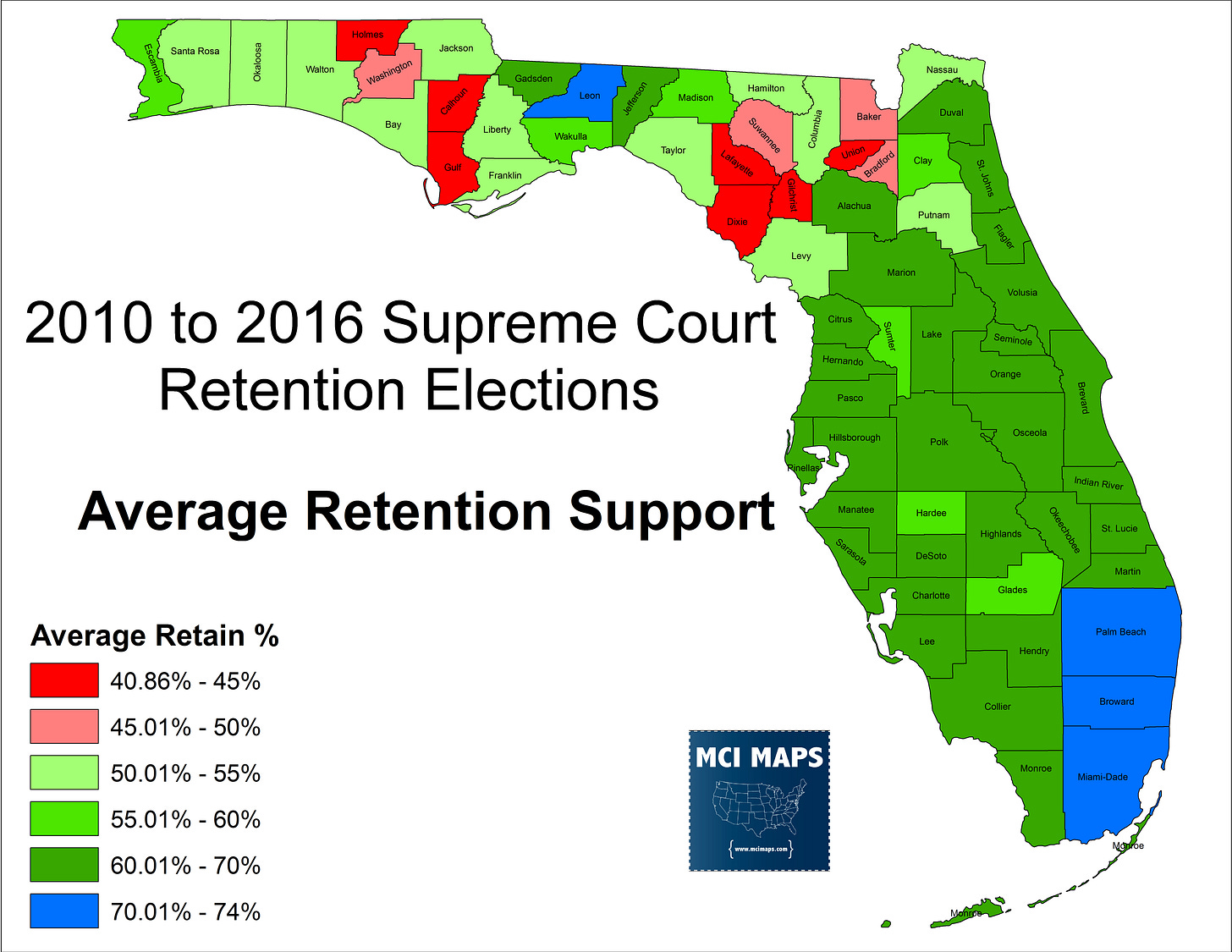

In 2017, I decided to write an article on retention elections in Florida. I found that there was a notable geographic divide in Florida when it came to retention elections. Regardless of a justice’s ideology, the retention of justices was much lower in rural/conservative counties. Meanwhile, retention was sky-high in blue pockets, but also in GOP suburbs and exurbs.

Multiple rural counties had voted against retention for every justice from 2010 to 2016 - even solidly conservative judges. In addition, in retention votes for the court of appeals, the rural counties again demonstrated a greater opposition to retention.

By and large, retentions were quiet affairs. However, two notable exceptions exist

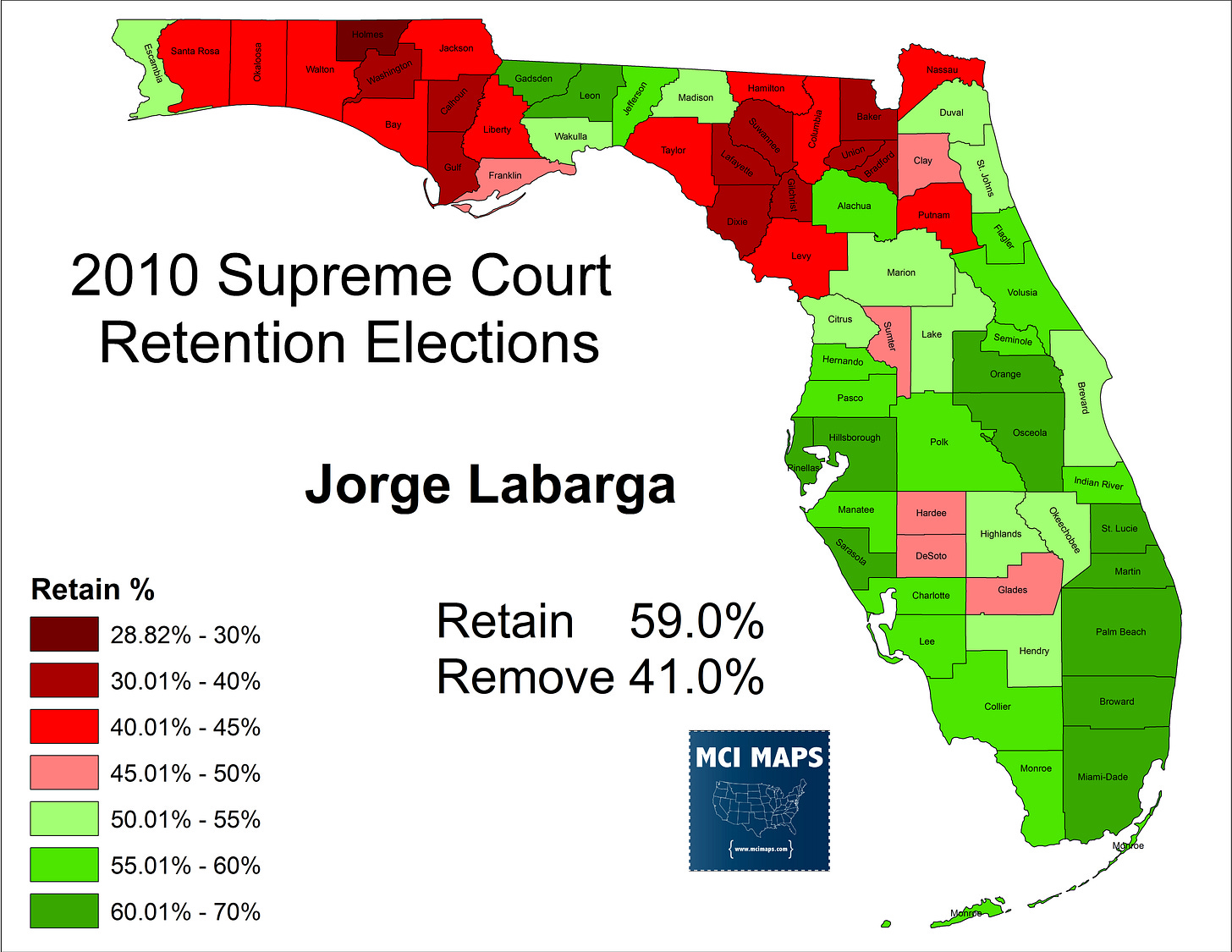

In 2010 - Liberal Justices Jorge Labarga and James Perry are targeted by Tea Party groups. The main sin is votes to remove an anti-Obamacare amendment from the 2010 ballot.

In 2012 - Liberal Justices Peggy Quince, Barbara Pariente, and Fred Lewis are targeted by out-of-state conservative groups. The effort is so serious that money is actually raised to defend the three.

Both of these efforts to oust liberal justices failed. I delve more into those votes here. The 2012 retention votes all secured over 65%. The closest any judge came to defeat was Labarga in 2010.

While these efforts may have failed, it helped solidify the image of the court as a liberal institution in Florida. This would effect future retention votes.

No retention votes took place in 2014. In 2016, however, three justices were up. Liberal Jorge Labarga was up along with Conservatives Ricky Polston and Charles Canady. Just one year earlier, Labarga was part of the 5-2 vote to order a special session on Congressional redistricting. Both Polston and Canady opposed that.

Despite the stark differences in the judges, all three had nearly the same state-wide share of the vote. Labarga got 66%, Polston got 67.8%, and Canady got 68%.

Labarga’s retention vote is below. The justice got overwhelming support in urban centers and suburbs. His only bad regions were more conservative/rural communities - especially in North Florida.

Justice Canady, meanwhile, was solidly conservative justice who was openly on Donald Trump’s short-list to replace Scalia on the US Supreme Court. Despite this, Canady’s worst areas were the same rural, conservative communities. While the losses were less than Labarga, they still show a rural rejection of the court. Meanwhile, Canady’s position on Trump’s short-list did not hurt him in any meaningful way with Democratic voters.

Comparing Canady’s retention % with Donald Trump’s % of the vote is worthwhile. The comparison shows how much Canady under-performed Trump in the panhandle. However, Canady was miles above Trump across the urban centers of the state.

After 2016, however, a shift in retention elections would begin.

The Shifting Court

After Democrats lost the 2014 Governor election, they were in bad shape with the courts. Multiple liberal justices were close to hitting the mandatory retirement age of 75 (with the state allowing justices to remain on till the end of the court term).

Rick Scott claimed he had to right to appoint the justices who would be termed out on January 8th, 2019 (the same day his term as Governor would come to an end). The court disagreed, and said the incoming Governor would make the selections. In principle, this made the 2018 Governor election a critical race for the court. However, it should be noted that even if Gillum had won that race for Democrats, the Judicial Nomination Commission (which is tasked with giving the Governor 3 to 6 names to chose from) was stacked with Scott appointees. This could have led to a showdown of Gillum rejecting all names. This didn’t matter though, as DeSantis beat Gillum. As a result, three liberals would be replaced with Conservatives. On top of a replacement from 2016. In total, four of the five liberals were replaced.

James Perry retired in December 2016

Barbara Pariente retired in January 2019

Fred Lewis retired in January 2019

Peggy Quince retired in January 2019

The court now sits at 6-1 Conservative v Liberal (with Labarga remaining).

As this shift in the court began, retention elections in the court also began to shift. It started in 2018 when Scott’s replacement for Perry, Alan Lawson, won every county in the state in his retention. This was the first time in a good while that retention succeeded in every county.

This continued into 2020, with DeSantis appointee Carlos Muniz winning every county as well. The precinct data reveals a stark deviation in past retention votes.

Compared to Canady’s retention, we see none of the rural opposition. Rural communities are on board with Muniz. Meanwhile, different Democratic pockets are the strongest in opposition. Retention fails or is notable weaker in multiple (but not all) African-American pockets of the state. A handful of white liberal communities also show opposition to retention. These are all areas that voted to retain Canady four years earlier.

How Muniz’s retention compares to Trump reveals a similar map to Canady v Trump. However, you will notice the extreme differences (the darker purples and darker greens) are not as present. While there is still a good degree of deviation, it is slowly moving toward parity (give it another 30 years).

In some cases, there is a clear slide from 2016 to 2020 with liberal white voters. One example I pulled was in a Tallahassee neighborhood called Indianhead Acres. This is a progressive white community that has a large number of government employees and activists. If there was ever an area were progressive insurgents do well, its here. Their retention vote shows a stark decline.

So, what is causing this? The general view is that as the court shifted conservative, the super-politically-aware voters (how many of you really pay attention to this stuff?) began to change their votes. On the other side, rural conservatives began to re-embrace the court.

Slate cards could also be a notable cause for opposition in specific geographic pockets. If you have every reported on or worked a campaign, you know slate cards well. In some areas, you can park at a polling site and have 5 slate cards handed to you before you reach the door. Slate cards arguing to vote NO could lead to statistically notable changes in voting.

The opposition to the Muniz retention also does show some similarities to the gaps that existed between Canady and Labarga vote totals in 2006.

2016’s votes show that while cities broadly voted to retain and rural region were more skeptical, there was a distinguishing factor, but in many areas the differences were small.

Below is a table breaking down the retention votes from 2010 to 2020. The shift is clear.

In my 2017 article, I broke down retention by the respective appeals districts in the state

The first district always demonstrated the weakest support for retention. In 2018, support went up to its highest share since 2008. It slid a bit in 2020 (thanks to Leon and Duval drops) - but what really stands out is the 4th’s titanic plunge.

That plunge was, of course, heavily fueled by Broward’s swing.

If I compare the Canady and Muniz retention votes (again, both conservatives) then we largely see the Democratic urban core swing against retention, while red Florida moves toward it.

The court is without a doubt a much more conservative institution at this point. It gives much more deference to the legislature.

How will this play out with redistricting? I know that’s what 90% of you are wondering. Well read my website this Friday for an article looking ahead to redistricting in Florida. I’ll talk more about the court, and other factors, then.