Issue #190: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 9: James Ford Re-Elected and the Klan march in Tallahassee

A quiet election and very intense march

Today is Part 9 of my series on Black political power in Tallahassee; a series looking at the rise of Black voting power and Black candidates in Florida’s capital city. Just a few days ago, I released Part 8, which looked at the 1976 candidacy of Harold Knowles; a 28 year old Black attorney. That issue delved into the horrible racially-coded attacks on Knowles from the major city paper; the Tallahassee Democrat. The race ended with Knowles losing by just 57 votes. The result was the commission remaining with just one Black commissioner; James Ford.

You can check out each previous issue here!

Today’s issue will look at Ford’s 1977 re-election. As I’ve discussed in previous issues, Ford always had a tight balancing act in a city that was majority-white and while racially moderate, was still prone to some racial anxieties. This was felt when Knowles had to answer for concerns he and Ford would always vote as “a block” because both were black; even though Knowles was likely more liberal than Ford. While Tallahassee was far from the racially-polarized southern town it was in the 1950s, there was still plenty of hurdles to overcome. In this vein, I will also be discussing an event that took place shortly after Ford’s re-election; when the Ku Klux Klan came to town.

Post-Script to the 1976 Races

In my last issue, I devoted the entire 1976 piece to the race for Commission Group 2, as it was the lone race with a Black candidate running. I did not have the space to discuss the other race; but I want to briefly touch on it here, as Black voters were an important voting block for the eventually winner.

The race for this city council seat featured six candidates, but I’m only gonna talk about the top two that advanced to the runoff. In the first round of voting, held February 10th, Neal Sapp, a businessman heavily involved in real estate, easily secured first place with 45% of the vote. Back in second was Jim Crews, a 30 year graduate student who worked with the America Lung Association as a Clean Air specialist.

In that first round, Crews won precincts overlapped with the FSU campus and broadly did better in student-heavy or faculty-heavy precincts. Sapp, meanwhile, won modestly across the rest of the city. However, Sapp’s strongest precincts were in the 90%+ Black. A race map of the city can be seen here. The three heavily black precincts (19, 17, and 21) all saw Sapp do around 35% to 40% points higher than Crews.

The dynamic continued into February 24th runoff. Crews backers, however, complained that Sapp was “riding the coattails” of Harold Knowles from the other race. This charge came from the fact that “Look Out” - a newsletter for the Black community run by community leader Steve Beasley endorsed both Knowles and Sapp for their respective races; and Beasley paid for radio ads promoting this fact. Knowles only made it clear all campaigns were independent of each-other and otherwise stayed out of the matter. Sapp pointed out his strong support in the Black community was due to many events in the area and his endorsement from prominent civil rights leaders like Reverend C.K. Steele.

When the runoff results came in, Crews dramatically closed the gap with Sapp, but not enough to pull off a victory. Sapp won by 5%.

In the runoff, the Black community remained Sapp’s strongest share. His 40% margins from the first round continued into the runoff, with both he and Crews consolidating the other candidate votes fairly evenly in the Black community. These were the only precincts were Sapp made a net gain vs Crews from the first round; while Crews closed the gap in “white Tallahassee.” In post-election interviews, Sapp said the focus on the “coattails claim” may have hurt him with some white voters. Crews conceded his weak support in the Black community cost him the race.

Black voters would not always be decisive in races between two white candidates, but in this race, they made a noticeable impact. With that, lets move on to 1977.

James Ford in 1977

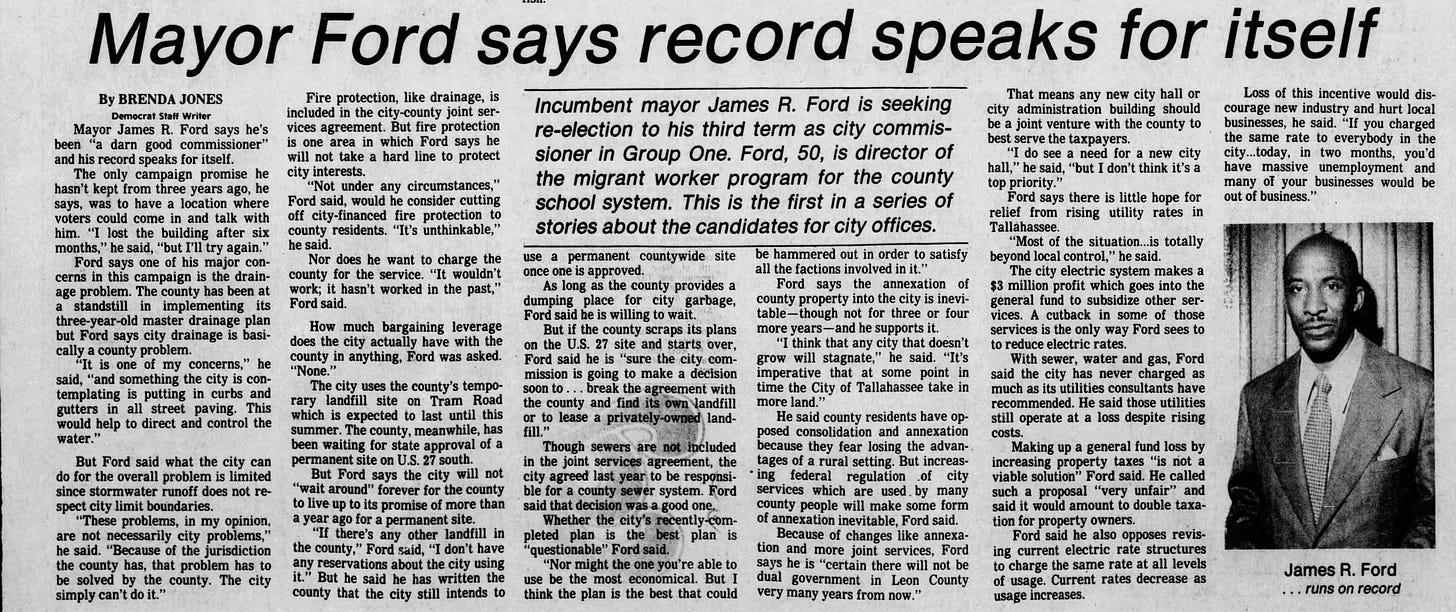

The 1977 city contests would feature two commissioners running for re-election. One was Johnny Jones, who won the infamous 1974 contest I covered in Issue Six. The other seat up was that held by James Ford, the city’s lone Black commissioner, who was then serving as Mayor - a position commissioners rotated at that time.

Ford was initially elected in 1971 and unopposed in 1974. He threaded the balance of being an advocate for Black voters while still being part of the white-dominated “good ol boy” club of Tallahassee. Thanks to his balancing act, Ford generated no major opponents for his re-election campaign. Ford wound up with just two opponents: Jim Shutes, a police officer with the city, and Rose Moore, a retired masseuse and perennial candidate. Neither were seen as real threats.

No major scandals emerged in the contest. Shutes or Moore had little tangible critique of Ford, giving voters little reason to abandon him. The election for Ford’s seat remained quit as the attention focused on the Jones race. Likely the biggest issue of the campaign was utility costs. Tallahassee runs its own utility company, so debates around pricing and infrastructure expansion often were a campaign issue.

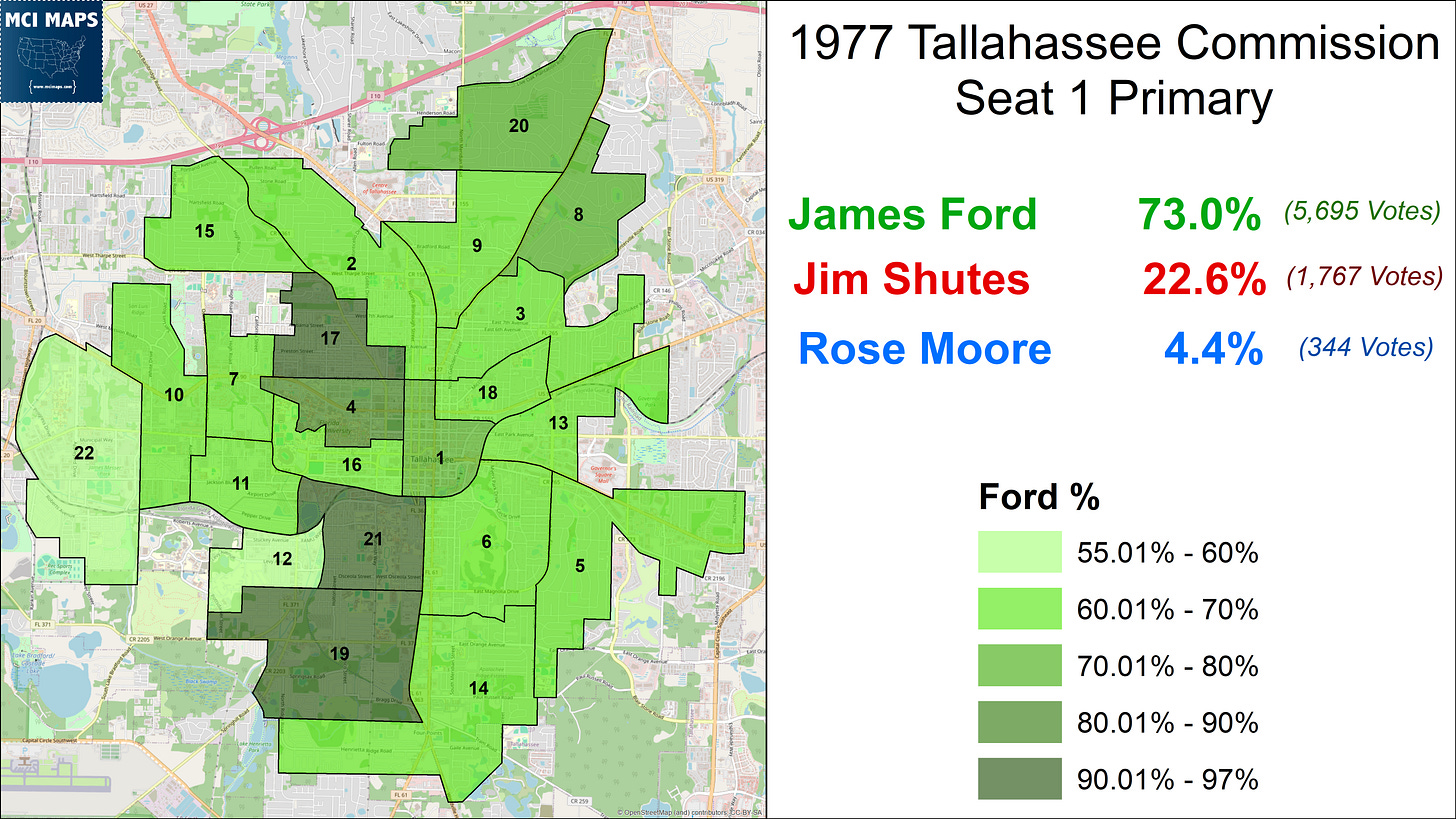

When primary day arrived on February 8th, James Ford was re-elected with 73% of the vote. Ford’s win was overwhelming, taking over 55% in every precinct in the city. Like previous Black candidates, he was of course strongest in the heavily Black precincts; topping 90% them.

Ford's win margin is even more impressive considering there was plenty of serious debate around city issues. Voters were hardly content with everything the commission was doing. This was seen most clearly in the race for Commissioner Johnny Jones’ seat.

While Ford was winning 73% of the vote, Commissioner Johnny Jones was securing just 27% and being forced into a runoff with newcomer Dick Wilson; who worked in state government. In a runoff two weeks later, Jones would lose re-election to Wilson.

Jones, if you go back and read Issue 6, was elected in 1974 when he narrowly made the runoff with Rosa Houston; a young Black female candidate who’s outspoken issues scared off white voters. As I discussed in that issue, Jones was not seen as a frontrunner then among the many white candidates running. When Jones made the runoff with Houston with just 22% of the vote, the white suburbs flocked to him to stop Houston. While he’d managed to build a base of support in the last three years, he ultimately was unable to hold onto his seat.

The Klan Comes to Tallahassee

Just a few days before James Ford was re-elected in Tallahassee, a much bigger news story began to dominate the city. On February 4th, a few days before voting, it was announced that the Ku Klux Klan had received a permit for a planned march in downtown Tallahassee. The permit was given to Bill Sturdivant, a Klan leader based out of Perry, FL.

The announcement led to protest from many residents, with opponents upset at the allowance of the permit. Now by this point the Constitutional right of groups like the Klan was settled law, so a permit denial was unlikely to happen. However, what angered opponents more was a perceiving that the city administration was not forceful in their condemnation of the Klan. Ford took flack on this front as well.

It should be noted that for all the issues that still remained with increasing Black political power in Tallahassee, this was not a city the KKK would be popular in. Tallahassee and Leon County broadly were still much more liberal than the North Florida region as a whole. I covered this in several articles, the two most important can be seen below.

Leon County Politics in the 1970s - A look at local and national races

When Leon County shed its Dixiecrat Heritage - A look at the 1976 Primaries

Tallahassee and Leon County were continuing to see monumental growth thanks to expanded college campuses and expanded state agencies. With each year it moved further away from its “Dixiecrat heritage.” This was culminated in the 1976 primary, which saw Jimmy Carter trounce George Wallace in Tallahassee.

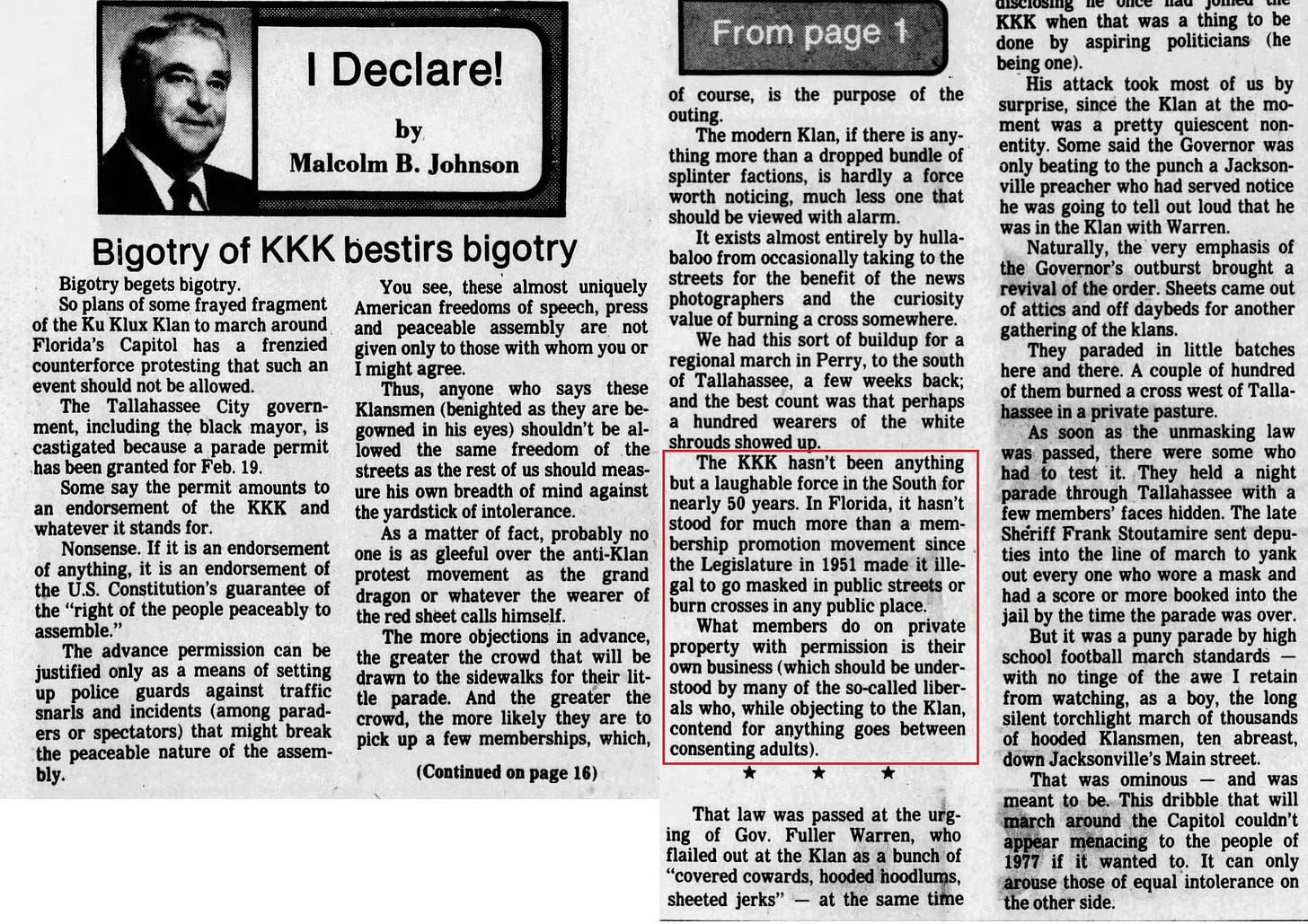

As such, it could be argued the best move with the KKK would be to ignore them. Let them march and give them no oxygen. However, considering the Klan to represented an ideology and viewpoint many 1970s Americans still held, showing firm opposition also is a valid course of action. What comes off especially revolting is lecturing people for taking that opposition stand. This was seen all too clear in the pearl clutching of the Tallahassee Democrat, which just HAD to write about the important rights of a group that stood for racial repression.

Malcolm Johnson, who I’ve cited here before, makes a point about ignoring them. However, he then equates protests with its own form of “bigotry” - an absurd statement. He also claims the Klan had not mattered for 50 years at that point, something completely insane considering the Klan terror that dotted the Deep South for decades before that point. The editorial is smug and self-righteous. The Klan does not need defenders.

The march was scheduled for Saturday the 19th. In the weeks leading up to this, the town was abuzz in debate on how to handle the unwanted intrusion. On the 14th, the Tallahassee Coalition Against Racism took the city government to task for their broad silence on the issue. The city was clearly in a hunker down, let them march, and move on, mentality. The opposition wanted the city to make it clear to the Klan “you can legally march, but we don’t want you here” - basically some shade thrown the Klan’s way.

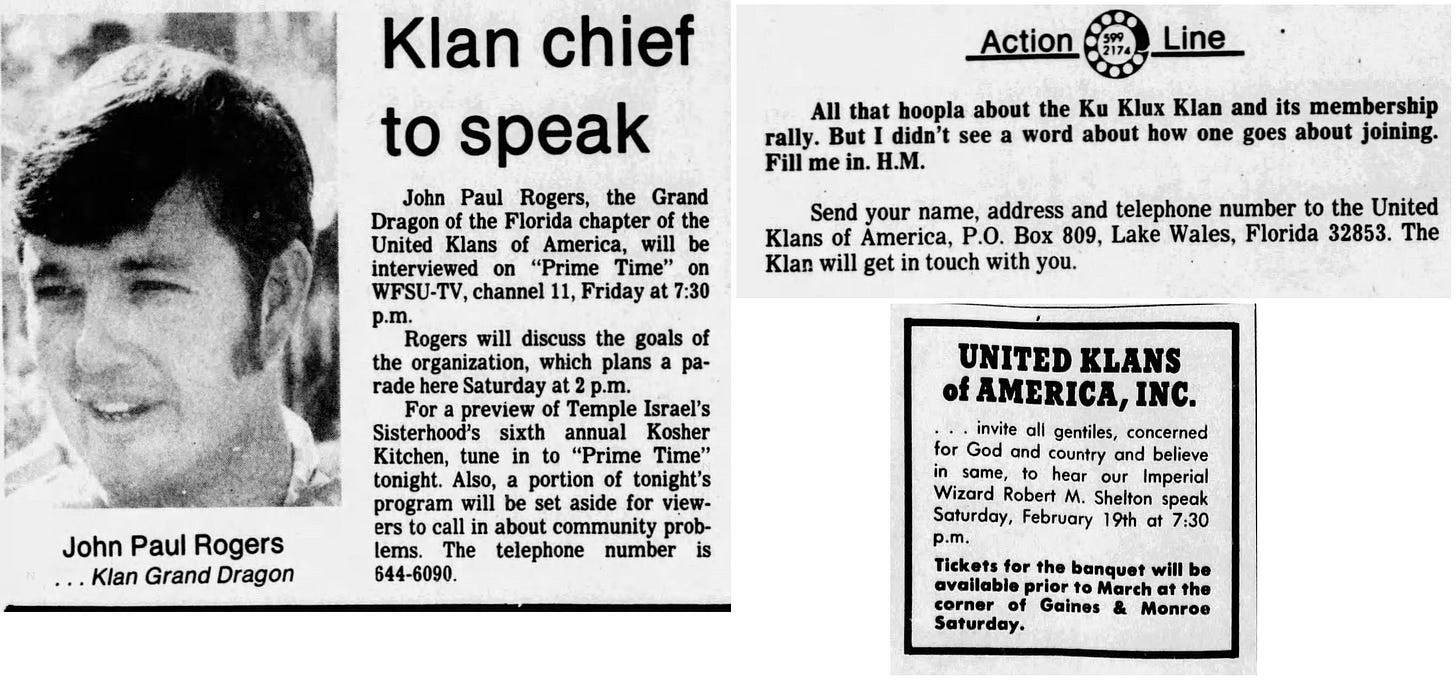

The argument to ignore the Klan and not give them oxygen would hold more sway if the Klan was not given ample opportunities to advertise FROM THE LOCAL MEDIA. As the march approached, the Grand Dragon, John Paul Rogers, was invited to talk at the local TV station, the Democrat ran paid advertisements, and reporters ANSWERED QUESTIONS ON HOW TO SIGN UP!!

You cannot say that protesting the Klan will only give them attention when they already have plenty of attention. Might as well see some opposition also covered.

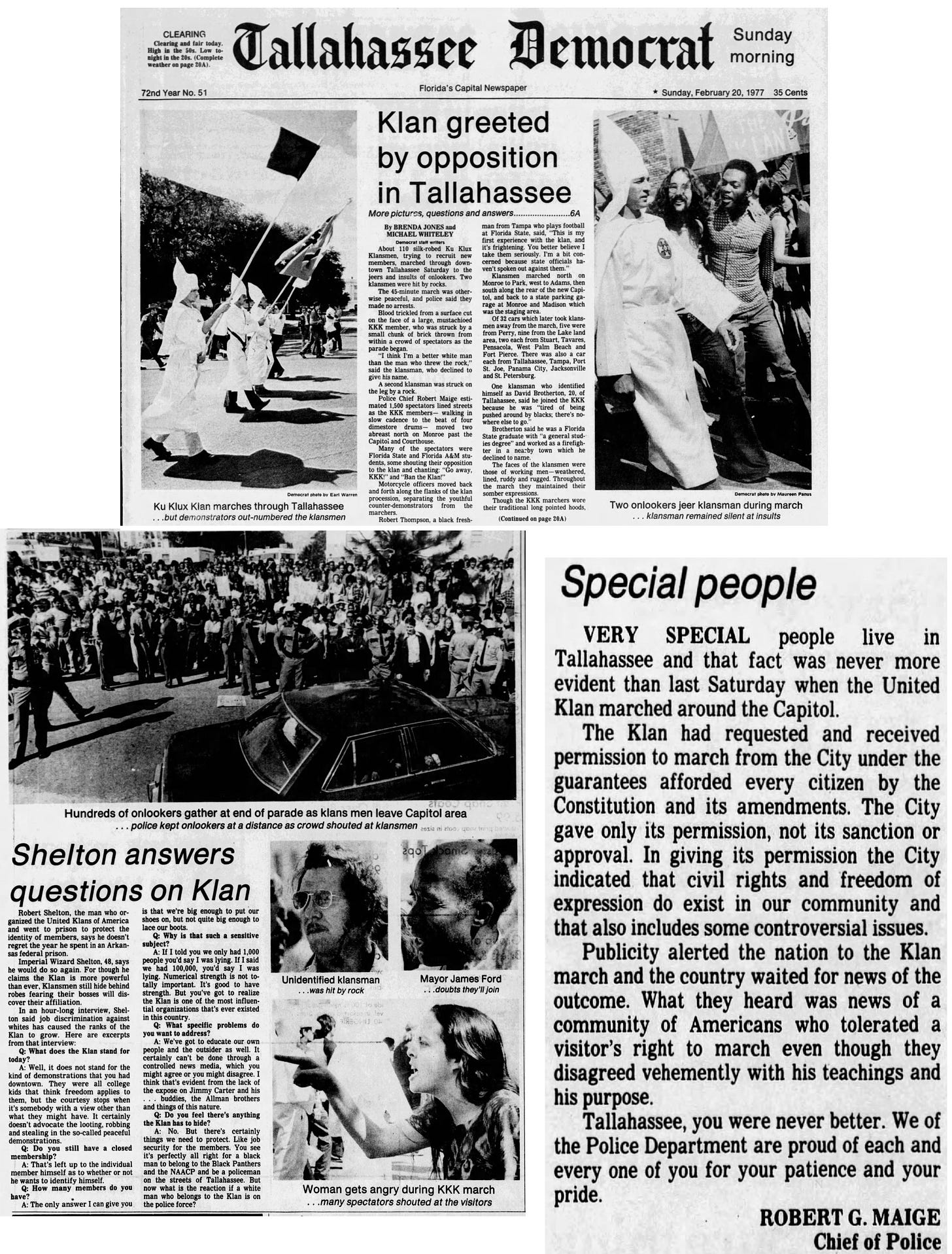

Tensions were high as the event approached. The city and county law enforcement were on high alert and the night before the march a bomb threat was called at the student union during a Black History Week celebration. Despite the tension leading up to the march, the rally itself did not see any major clashes. Over 1,000 counter-protestors easily outpaced the Klan, but no major fights broke out. A few projectiles were apparently chucked, but nothing of real note. The Chief of Police offered an editorial days later commending the city for keeping cool.

The Klan, by its own admission, was shocked by the opposition they received in the city. Apparently recent marches they’d held in other towns had not yielded such loud opposition.

In the weeks following the march, the letters to the editor were filled with people arguing about the protests to the Klan. Several editorials called the counter-protests “shameful” and acted like the Klan was brutally gang assaulted in the street. Again the fact the Democrat would run them speaks poorly of them for that time, especially one editorial from a Perry woman who blamed the protests on “foreign exchange students.” I won’t dignify the racist trash with coverage here. Instead I’ll highlight this editorial taking the paper to task for its framing of the counter-protest.

That any ink was given to defend the Klan is shameful. What is good to know at least is that when the day came, the Klan was far outnumbered by its critics. The reactions of the major paper, however, showed much work was still needed in the capital city.