Issue #117: The Year Leon County Florida Shed its Dixiecrat Heritage

George Wallace was the canary in the coal mine

In Florida today, Leon County is known as one of two blue islands in Florida’s north panhandle. Along with majority-black Gadsden, Leon, home to Tallahassee, is the only other guaranteed blue county. This is clear when looking at the 2022 Gubernatorial landslide.

What drives Leon County’s Democratic makeup is several factors.

28% of its voters are black

It hosts the FSU and FAMU universities, as well as Tallahassee Community College, with students being a big voting block downtown

It is home to many democratic-leaning state and local government employees, creating a base of white liberals.

It’s Republican-leaning suburbs have overtaken the more conservative rural voters.

46% of the population over 25 have a Bachelors Degree or higher, the highest in the state.

In 2020, even as Florida swung to the right, the county actually moved a bit more to the left, with its shrinking rural population being the biggest source of right-wing shifts.

While Leon is a urban-suburban-democratic island in the panhandle today, it was not always the case. Like the rest of the panhandle, Leon was part of the Jim Crow south for many years. So when did that change? Well, according to a Tallahassee Democrat article, it may have been in 1976.

But lets look back to investigate.

Early Leon History

In the 1940s, Leon was a rural and low-populated county. In an era of Tallahassee being a sleepy capital city town, where life only really picked up when lawmakers came into session, the area was not much different from the rest of the panhandle. This rural nature (the county didn’t have many paved roads till the 1900s and was a radio dead zone for many years) led to many pushing from lawmakers to move the capital. I covered this saga in my 2019 article on the topic.

It was a firmly one-party county, giving near-universal support to Democrats. In 1940, FDR did not fall behind 80% in a single precinct.

At this time, Leon was still part of Jim Crow, and black voting rights were brutally suppressed in the region. In neighboring Liberty County, efforts by black voters to register in 1954 were met with cross burnings and threats of violence - eventually leaving no black voters registered there. Several panhandle counties did not see registration increases until the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Majority-black Gadsden was one of these; having less than 100 black residents registered until the VRA. I covered Gadsden’s history here.

In Leon, black voter registration did not need the VRA to get started. Efforts to register black voters in the early 1950s began. The city was rocked by bus boycotts in 1956, but with a more racially-moderate Governor in Leroy Collins, black political life began to emerge in select counties. Tallahassee had a base of civil rights advocates, with Reverend C. K. Steele being a major figure in the civil rights push. To this day in Leon County, the Democratic Party hosts a “Collins-Steele” dinner to honor both. With an NAACP base in the city, despite plenty of white opposition, black residents began to engage electorally.

By 1956, 135,000 black people had managed to register in Florida, with many in urban centers. 25,000 came from Duval, 16,000 from Dade, 8,000 from Hillsborough. Leon County had 3,800. Registration rates varied by county, with some panhandle counties having decent numbers of black people registered (like Jackson) while others refused to allow registration - like Gadsden or Liberty.

In 1956, black voting power was flexed in the Presidential contest. That year saw Ike Eisenhower defeat Adlai Stevenson in a rematch of 1952. Stevenson, while on paper more progressive, struck a more moderate tone on race relations compared to four years earlier. This earned him more support of Jim Crow politicians who sat 1952 out. As a result, black voters defected from Stevenson and toward Ike. In Leon, this switch led to Stevenson almost losing the county, a first in that era.

I don’t have exact racial data by precinct, but the local paper pointed out that Precincts 9 and 11, the sources of the biggest swings, had the largest black populations. The 25% swing against Stevenson in Precinct 11, which was heavily dominated by southside black voters, stands out. Stevenson, meanwhile, still held the rural white “dixie” precincts.

As the Civil Rights fights of the 1960s expanded, the white residents of Leon County broke from Democrats. While JFK held the county in 1960, Goldwater became the first Republican to win the county in 1964.

In 1968, Leon voted for independent George Wallace, who ran on a populist segregationist ticket. He dominated in the rural white precincts and he and Nixon split suburbs. However, the black population of downtown and the north did show their strength in giving those precincts to Humphrey.

At this point, Leon was growing in population, and as such the city borders were expanding. The original city only made up one square mile and only modestly expanded through the next century. By this point, however, more annexations and development began. By my estimates, Humphrey did take the city, and the difference between the downtown and rural communities is clear.

Tallahassee itself would continuously be more progressive than the County as a whole, but it was still a southern democratic town. In 1971, it did break a major barrier when James Ford became the first black man elected to the City Council since reconstruction. He won along with a progressive white candidate in Loring Lovell.

Both candidates did better in the more racially diverse west end of the city. The city still had plenty of racial voting, but the data shows that still plenty of white voters on the east end did vote for Ford.

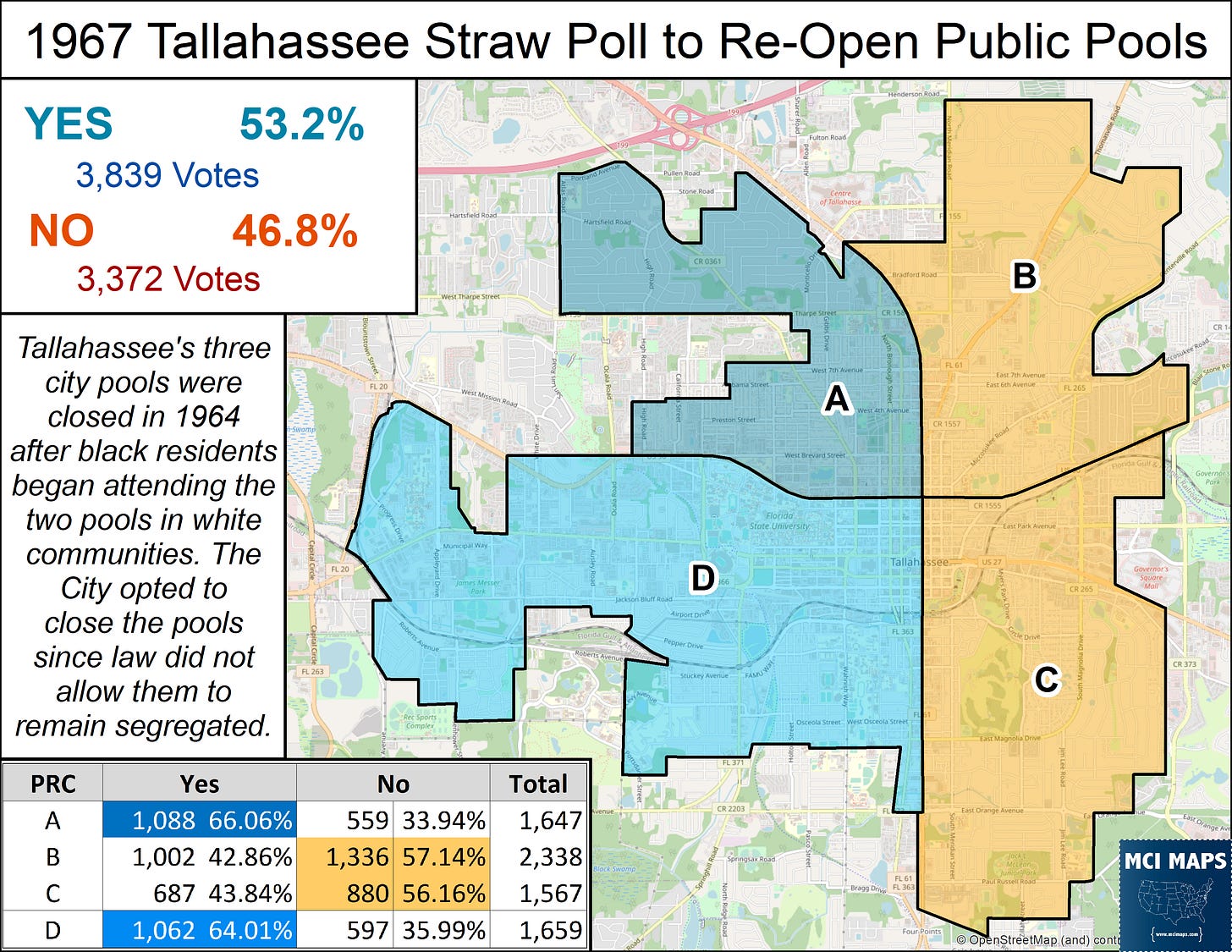

Just four years earlier, the city held a straw poll over its public pools. Until 1964, the city had 3 city-run pools, one for black residents and two for white. The Civil Rights Act meant this segregation must end, and when black residents showed up at the white pools, it led to tension and the city shutting them down. After years of debate, commissioners agreed to put the issue as a straw ballot to the voters.

The re-opening of the pools passed with a similar east-west split. Newspaper coverage from the time largely sided with re-opening, with columnists urging a move away from the racial tensions of the past. This was coming at the very same time Leon was facing pressure on the moving of the state capital; with Orlando and Miami lawmakers arguing the city was too southern and backwards. This referendum came at the same time the county voted to become WET, which I cover in my 2017 article.

The Decline of George Wallace in Leon

The saga of George Wallace is strong indicator for the county and city changing electorally. First, in 1972, George Wallace opted to run as a Democrat and sought the nomination. He ran on a conservative platform, and while he moderating a bit on race, it was clear he was the candidate of Jim Crow (to whatever extent segregation could be pushed informally). Racial issues moved to items like busing, reoperations, and federal aid in civil rights.

In 1972, Wallace won every Florida county, including Leon.

Wallace’s panhandle support was weakest in Gadsden and Leon, but he still comfortably took the county. Of note, George McGovern did take FSU, which was continuing to expand. In addition, Shirley Chisholm, the first major black candidate for the democratic nomination, won majority-black southside and Frenchtown.

Of course, while Wallace took the county, he did not take a majority. A map of Wallace vs every other candidate showed his weaknesses. He was unpopular in the black community and student areas.

Wallace also failed to secure a majority in the expanding suburbs that moved out of downtown. The black population of North Leon (which sit largely in Miccosukee in the east and the NW corner of the county on the west) also flexed its muscle to deny Wallace majorities there.

Wallace would never get the nomination, subject to an assassination attempt that left him paralyzed. However, he made one more play for President in 1976.

Heading into the 1976 primaries, Wallace was betting big on Florida. Jimmy Carter, who was part of the new wave of more racially-moderate/progressive Democratic Governors, had several key victories already under his belt. Wallace believed he could win Florida, and his campaign team predicted they would hold Leon County.

Instead, Wallace was badly beaten, losing to Carter by 12 points while losing by 4% statewide.

Leon was the only county in the panhandle to defect from Wallace. Gadsden was still majority-white in registration. In Leon, the black population was firmly in Carter’s camp, while the suburbs largely rejected Wallace and went with Carter. Students also backed Carter over more liberal options as part of a “stop Wallace” effort.

The Wallace v Everyone map shows his strongest appeal was limited to the rural fringes of the county that remained heavily white.

This was a massive failure for the Wallace campaign, and he would never recover in the contest.

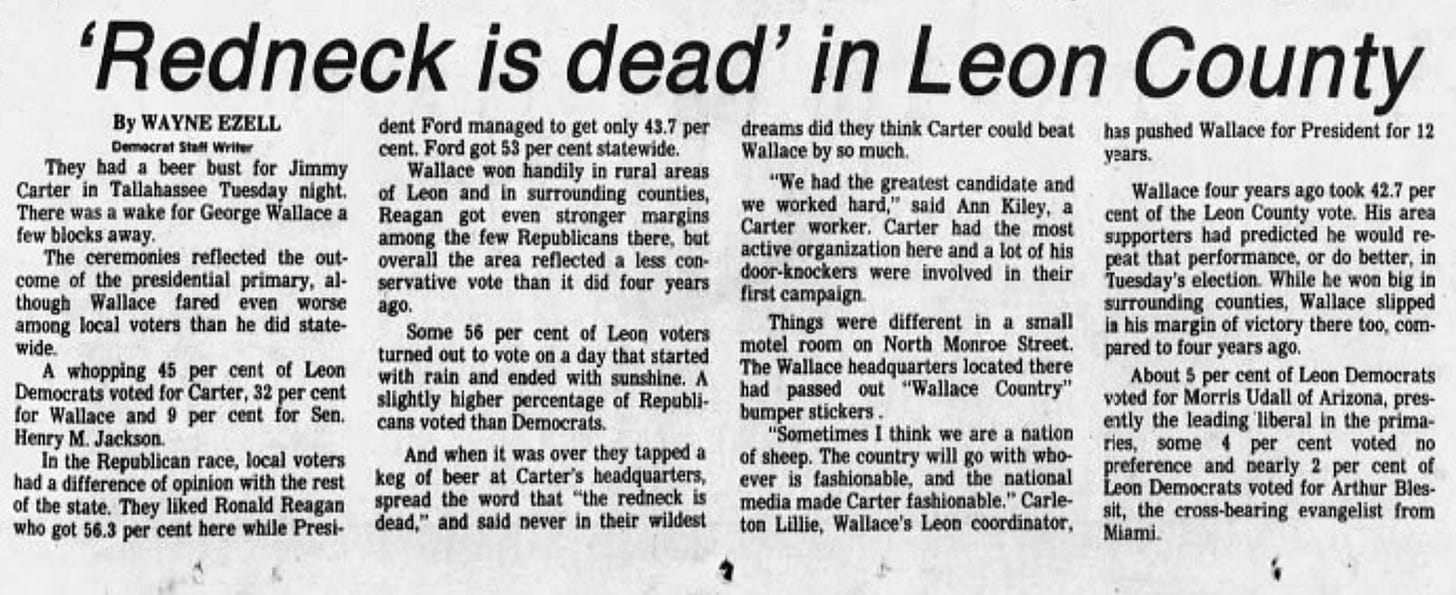

The next day, the Tallahassee Democrat made this proclamation.

The absolute bitterness of the Wallace campaign coordinator is delicious.

Carter would go on to win the county in the general and would narrowly hold it in 1980.

Did Redneck Die in 1976?

The newspaper headline is obviously dramatic to prove a point. There is no one year anyone can point to as “ah the moment it all changed.” Things were clearly heading in a direction away from Jim Crow, however. Leon had backed Wallace in past races, but the county was expanding in population rapidly, changing its complexion. Back in 1944, only 30,000 people lived in Leon County. By 1980, it would be 160,000. The expanding state bureaucracy and university presence created a much more left-leaning population.

The last times Leon voted GOP for President was 1984 and 1988. From that point on its been heavily Democratic and more progressive than the rest of the state. It is not a left-wing mecca, as its moderate suburbs combat with young progressives, but these groups reject the old Dixiecrat heritage.

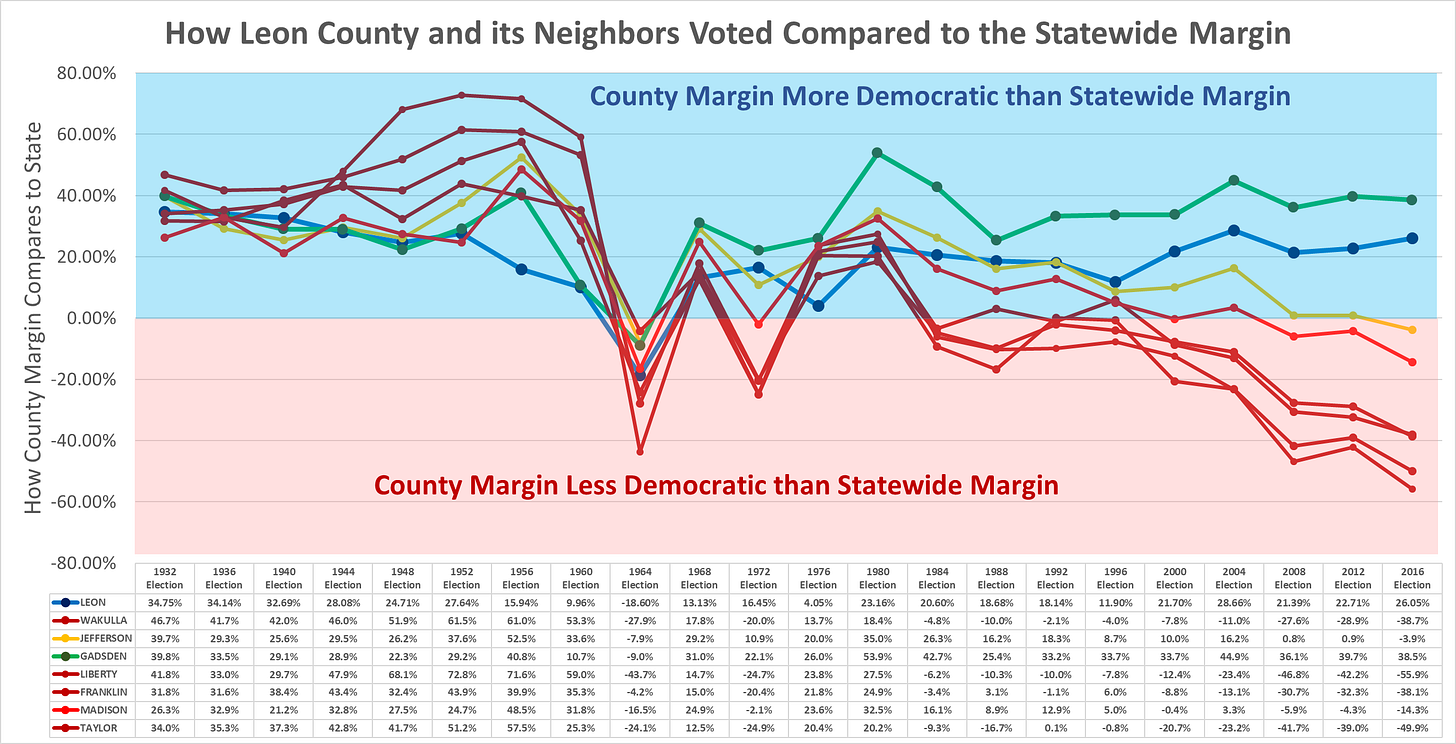

I graphed out how Leon and its panhandle neighbors all voted for President from 1932 to 2016, specifically highlighting if they voted to the RIGHT or LEFT of the state margin. As the graph shows, 1964 saw a massive swing to voting to the right of Florida, followed by several years of chaotic swings.

However, by the late 1970s, Leon and Gadsden would cement themselves as perpetually left-of-the-state. Meanwhile, the rural neighbors began to slide further and further to Republicans as the party embraced conservative racial policies. Neighboring Jefferson County, which is 35% black, remained modestly left-of-state until recently, and has now herded to the right as its white voters reject Democrats. Many of the counties with very small black populations have become deep red counties.

While any specific year cannot be pointed to as the lone moment “redneck died” in the county, it is clear Leon was undergoing a major shift in sentiment by that point. The 1980s in Leon would be filled with tension as black voters sought representation at county government, which eventually led to the creation of single-member districts. It still would not be until the 1990s that a black candidate would win county-wide, so by no means am I claiming 1976 marked the beginning of “super racially progressive Leon.”

Today, black candidates win countywide and citywide with little discussion of race coming into play with the broad population. I want to delve much more into the 1980s and 1990s debates in future articles. The shifts over the last 30 years are a major story themselves. This entire post is a MASSIVE simplification of a great deal of complicated history. A large amount of info is on the cutting room floor just to keep this post under the max-size substack allows.

So did redneck die in 1976? As I see it, the Carter stomping of Wallace is a perfect symbolic moment to describe Leon’s transition - which would continue for another decade more to come. 1976 is at the very least, an important watershed moment, but much more work was still left to be done.