Issue #169: Tallahassee Series Supplemental: Leon Politics in the 1970s

Advancements and setbacks

As many of you know, I have been working on a series of article’s covering the fight for political representation in Tallahassee’s black community. I began my series in the 1957 election, the first time since reconstruction that a black candidate ran for city council. I am currently in Issue 4, a year after James Ford became the first modern black commissioner in 1971, but well before black voters were as important a political force as they are now. My series will continue through the 1970s and 1980s, and I have specific ending in mind. The link below has all four issues.

Black History in Tallahassee Elections Series

As I work on Issues 5 & 6, which cover campaigns in the middle/late 1970s, I found myself needing to discuss broader national/regional trends that influenced Tallahassee. However, in the interest of keeping those pieces about the city campaigns themselves, I wanted to create this supplemental that offers more context to where Tallahassee and Leon County sat in the broad political trends.

This is not critical to following the way Tallahassee elections would progress through the 1970s, but it helps put more context into them. For this I have two areas to cover; Leon in the context of national/state trends AND a look at black candidates in countywide contests.

Leon County in the National Political Environment

In my earlier issues of the Tallahassee series, I covered how Leon County was moving in the broad national environment. Through the 1960s, Leon remained firmly southern in its politics, voting for Barry Goldwater in 1964 like all its North Florida neighbors. However, thanks to a small liberal white population fueled by the FSU, FAMU, and the Florida state agencies, as well as a growing black voter base, the county was never as racially conservative as its neighbors. It would back racial liberals for their time like Leroy Collins but likewise vote for George Wallace in 1968.

By the 1970s, however, changes were happening in Leon County and Tallahassee. Population growth continued, with the city expanding in size as new development came in. From the 1950s through 1980s, the county would grow by 40% on average each decade. From 1960 to 1970 the county went from 75,000 to 105,000 residents. Much of this growth was the expanding state government and University Systems. This led to the older southern family dynasties losing their influence. This local shift was seen on the national stage as well, as these families were more conservative.

The 1970s were not the moment Leon County went from conservative to the lefty/liberal kingdom it is today. However, it is the decade it, as I said back in Issue 117, shed its “Dixiecrat Heritage”.

That issue focused extensively on the 1972 and 1976 Presidential Primaries, which showed Leon move from backing folks like George Wallace to backing candidates like Jimmy Carter. I largely argue 1976 is when Leon moves out of the “solid south” category for good.

Leon’s elections through the 1970s are a mix of contradictions. Moments of backing more liberal candidates and other times backing more conservative issues. One constant though in the 1970s is black candidates and voters showing increasing political strength.

The 1970 US Senate primary highlights this well. That year, in a race eventually won by Lawton Chiles, Broward County attorney and future congressman Alcee Hastings ran for the democratic nomination. Hastings, always an underdog in the race, was still a force in the primary thanks to his strong support with black voters. In his time as an attorney, Hastings fought for the integration of Broward schools, leading to a strong following with black voters and a scorn from conservative whites. In Leon County, Hastings took 17% of the vote, winning the county’s 3 majority-black precincts.

Hastings would not win that race, but his candidacy highlighted a continued growing black political strength emerging in Florida.

Hasting’s support in the southside of Tallahassee and Frenchtown would mirror the support that Shirley Chisholm, the first black candidate for the Democratic Presidential Primary, would get in 1972. That year, while Wallace took the county and state with a plurality, Chisholm won Tallahassee’s black community while George McGovern took the FSU campus. I have maps of those races in my Issue 117 piece linked further up.

The same day as the Presidential Primary, Florida voted on a series of straw ballot measures. One of them called for an end to mandatory bussing to de-desegregate the schools. This was a very controversial program, even contentious among racial moderates, but something heavily backed by Governor Reubin Askew; who campaigned against this measure. However, the proposal easily passed, including within Leon County.

Leon gave over 64% of the vote to ending bussing, but this was notably weaker than surrounding counties, or even much of the state. Opposition to the ban was strongest in the city’s black population, students, and downtown white liberals. You can read even more about this 1972 campaigns in a special Patreon Post I did back in February.

In the 1972 general election, Leon, like every Florida county, easily backed Richard Nixon. However, the county’s 63% was much lower than its neighbors or even the whole state. The downtown city area was far less on board with the President. The best estimate is that McGovern got 45% in the city of Tallahassee.

I included the county commission race from that same day, as it marked an important shift in local politics. That was the first time a major Republican effort for commission took place. The result was still a blowout Democratic win and Leon would remain down-ballot for almost all of its history.

The 1972 Nixon win aside, the 1974 contests would show that Leon was not moving in a more conservative direction. Before we get into that, however, the county went through a re-precincting process that finally matched the precinct lines with Tallahassee city borders. I also managed to get some registration by race data for 1974.

The county was just under 18% black in terms of voter registration, with that population heavily clustered in the downtown communities and in historic Miccosukee in the Northeast.

There are two key 1974 races I want to look at here. First, in the US Senate race, Democrat Richard Stone secure a weak win thanks to a split in the conservative vote. While Republicans nominated Jack Eckerd, known best for his pharmacy chain, John Grady, a Doctor and Mayor of Belle Glade, ran as an independent and took 16% of the vote. Stone won with just 43% statewide, but he did secure a majority in Leon County.

Grady had the strongest support with rural voters, and that was seen with him taking the county’s most rural, white precincts. However, Stone easily took the county with 52% and got 56% in Tallahassee, well above his 43% statewide.

That same day, Governor Reubin Askew ran for re-election. As a mentioned before, Askew was a supporter of integration busing and represented the wave of “New South” governors. As a result, Askew lost a great deal of support from the rural panhandle voters that backed him in 1970. He lost much of the panhandle, save for Leon and its neighbors with sizeable black populations. Within Leon, Askew easily won across the county, only losing a few of the rural white precincts.

Askew’s dominant win in the county, with 69% in the city, was a critical repudiation of the right-wing criticism of the Governor, which ranged from issues of taxes, government expansion, and racial politics. His strong showing in the same suburbs that voted for the 1972 busing ban showed many of the suburban voters, while not being as racially progressive, were also not transforming into reactionaries.

Two years later, Jimmy Carter would bring Leon County back into the Democratic column for President. Gerald Ford showed strength in the city and county’s emerging suburbs and exurbs. Carter took 54% in the county and 56% in the city, both above his statewide average.

That map shows the dynamic that would begin to emerge more in the county, the Democratic downtown vs the Republican suburbs. The Presidential map also highlights well an emerging planned suburb that would eventually be annexed into the city. The dark red PRECINCT 29 in the Northeast covers part of what is now known as Killearn Estates. We we see more of that further into my city election series.

Black Candidates Countywide

On the local front, Leon County would spend the 1970s being led by white Democrats. Black candidates did make plays for local office, but would almost universally come up short. However, several of these races did highlight growing black political strength, especially in the city itself.

In 1970, Edwin Norwood, who’d lost a city council bid back in 1969, ran for School Board. Norwood challenged T.B. Revell, an incumbent running for re-election at a time the district was under heavy criticism over resources and school locations. Norwood, if you check back to his bio in my Part 2 piece, was a well accomplished academic who taught at FAMU. In his bid, he would lose the school board race, but came closer than any black candidate in the recent era.

Norwood kept it close by running up big margins in the black community and doing well with liberal whites around the campus. Norwood also won the North county, which still had a sizeable black population. Critical for Norwood was not getting blown out in most of the whiter surrounding precincts. One important item, however, is that Norwood almost surely won the city in that school board run. Precinct borders do not match the city boundary, but some rough math would say Norwood got somewhere between 52% and 56% of the vote in the city.

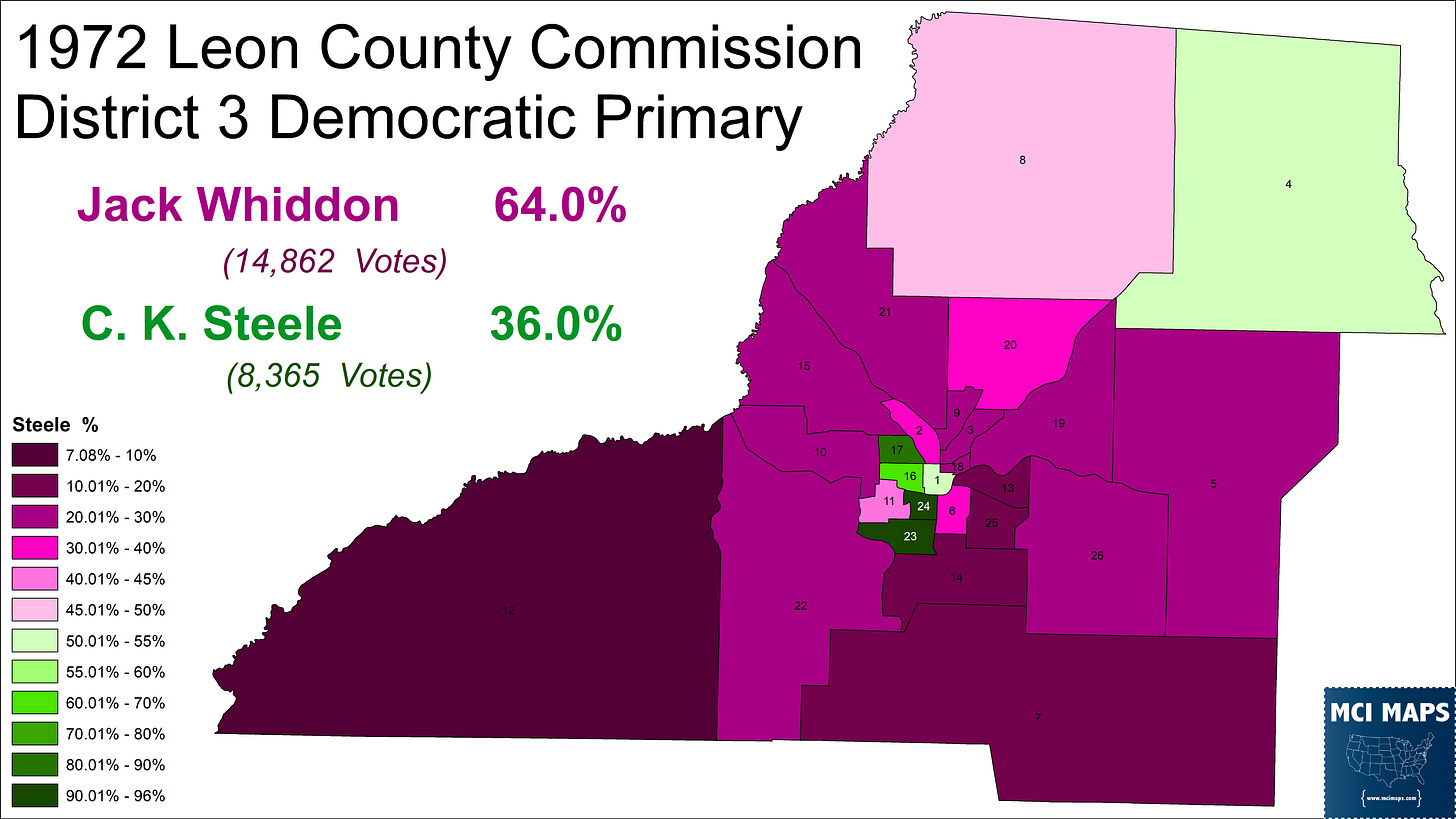

Two years later, however, the struggle for black candidates countywide would be readily apparent. That year, Reverend C. K. Steele challenged incumbent Jack Whiddon in the Democratic Primary. Steele, if you read back to Issue 1 in my series, was a key leader of the 1956 bus boycott that eventually saw the end of desegregated public busses in the city. The bus boycott is a seminal historic moment in Tallahassee history, and Reverend Doc Solomon, one of Steele’s deputies, ran for city council in 1957. I cover the boycott much more in Issue 1 of my Tallahassee series. Sixteen years removed from the boycott, Steele, who remained active in civil rights issues, ran on issues around community resources and services. However, Steele lost by 28 points, doing very poor in the heavily white parts of the county.

Even within the city, Steele likely garnered around 42% of the vote. Steele was a well respected community leader and today is regarded as one of, if not the most important, civil rights leaders for the city/county. However, its easy to see many of the white moderates showing little interest in a candidate so “aggressive” on issues. You can see more of that sentiment from Issue 3 of my series, which highlighted how black candidates had to work extra hard to not come off as too outspoken or “aggressive”. This type of casual racism still permeated the area at the time.

The 1976 contests, however, would see Leon break new ground. That year, Doris Alston became the first black candidate to win countywide since reconstruction. Alston was an incumbent board member, having been appointed by Governor Askew to fill a vacancy. Alston, who also taught at FAMU, made a bid for her own term in the 1976 and defeated retired schools employee James Harbin. The campaign did not see race be brought up as a major issue, rather focused on school issues for the time.

Alston won with 57% in the city of Tallahassee and did well across many voting blocks, only losing precincts by modest showings. While there is racial correlation to the vote, the Alston margins compared with Steele or even Norwood show how much stronger she was with whites.

Alston’s win is often overlooked in the discussion around black representation in the county. This is likely because she was elected as an incumbent who had at least some record to run on. Unfortunately, this was likely a strong point, as future countywide black candidates would all falter in bids for school board and commission. This would lead to lawsuits and eventual changes for both the county commission and school board to go to single-member districts in 1986 and 1990 respectively.

Regardless of how much being an incumbent helped, the fact that Alston won is still a monumental moment for the county. It highlighted the changing politics of the county into a more progressive bent and further away from rural conservative heritage.

This wall be discussed more in my upcoming issues in the Tallahassee city elections series.