Issue #175: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 6: Rosa Houston vs The Establishment

A crowded race gets nasty at the end

Today is Part 6 of my series on Black political power in Tallahassee, Florida. Last week, I discussed the 1973 candidacy of Rosa Houston, the first Black female candidate in modern Tallahassee. In that issue, I discussed how Houston’s vision for more aggressive city involvement in aiding poorer voters did not inspire support from the more conservative city of that time. Houston had little white support in her 1973 bid, but had very strong support with Black voters. She also far out-performed considering her lack of funds.

Today’s issue will look at Houston’s 1974 bid, which further highlighted the resistance to such outspoken Black candidates at the time. I recommend reading Issue 5 before continuing, as it adds important context for Houston and Tallahassee at the time.

Lets dive in!

Tallahassee Expansion in 1974

Before delving into the campaigns, a quick look at the dynamics in Tallahassee at this time. Following the change in election laws passed by the legislature in 1973 (more details in Issue 5), the county and city underwent a major reprecincting process. The city no longer would use just 4 precincts, but instead 22. This increase allows for much more detailed look at demographics and election results at the neighborhood level.

In 1974, Tallahassee was 20% Black in terms of its voter registration. Those voters were heavily concentrated in Southside and Frenchtown. Meanwhile the FSU and student community, heavily clustered in precincts 4 and 16, were more diverse and also full of more liberal white voters. Meanwhile, much of the rest of the city was overwhelmingly white, reflecting the effects of segregation that were in play for decades. Many white neighborhoods had racial covenants that explicitly said Black residents could not reside in the neighborhood. One prime example of this was early Betton Woods, which had such rules and was 100% white as a result.

Racial covenants stopped being enforceable in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act. Even then, the effects of those restrictions would last to this day. The racial covenants can still be found in old deeds, even thought they are unenforceable. However, the recent discovery of one by a Black home buyer stirred up a new call to go back and censor the old language. These covenants were not everywhere. However, the addition of historic redlining, as well as the social pressure to not move into a white area, ensured Tallahassee would be heavily racially segregated in the mid 1970s.

While Tallahassee had elected James Ford as its first Black commissioner in 1971 (Issue 3), Ford lived in these whiter areas, serving as Assistant Principle of Leon High School, and was largely viewed as “respectable,” aka someone who did not focus on Black issues as much. Candidates viewed as too “Black centric” still scared off these whiter communities.

While the city retained these racially conservative views, the area was undergoing rapid change. The population was continuing to increase, going from 48,000 people in 1960 to close to 75,000 by 1974. This growth came from a major population boom across Florida, but also from specific local drivers. For one, the Florida State University system was rapidly expanding. Over the last decade, FSU enrollment doubled from 10,000 to 20,000. FAMU, the city’s historically Black college, continued to grow in prestige. On top of that, Tallahassee Community College was created in 1966 and would become another driver for students to come into the county. On top of this, 1973 was when the massive new Florida Capital Complex broke ground. This was the transition of the Florida government from the small statehouse to a sprawling legislative and administrative complex. The old capital sits in the front as a museum, while that massive structure…. that may or may not look like something… sits behind.

Growth in Government would mean growth in state employees, many of whom were more liberal. At the same time, Tallahassee was seeing work begin on I-10, the major highway that would connect the city to Jacksonville and the rest of Florida. This was the time that many of the physical development Tallahassee folks know today began to really take root.

The 1974 Primary Campaign

I discussed Houston’s biography in 1973, so definitely go there for her backstory. The short version is, Houston was a young but well-regarded administrator and civic leader. She graduated from FAMU, taught at FSU, and was involved in many civil administration studies and projects; including a panel to see how the city should respond to all the rapid growth. After her 1973 loss, which was still a strong showing, it seemed for sure she would run again. She remained very politically involved through 1973, including being the spokeswoman for the NO side of the November referendum to consolidate the city and county governments; which failed at the ballot.

In January of 1974, Houston announced she would run.

Houston would again maintain a progressive and aggressive vision for the city being involved in many aspects of daily life. It would again make her the most progressive candidate in her race. That race, like 1973, was crowded, with Houston and five others vying for the open seat. Her opponents were….

Ben Tucker - Former Chairman of the Leon-Tallahassee Zoning commission. Major backing from developers. Raised $3,900 ($27,000 today).

David Hirsch - Private practice attorney with former work in municipal codes. Part of drafting of 1973 Consolidation Charter. Also developer backing. Raised $3,100 ($21,000 today).

Branyon Cobb - Gun shop owner with military background and good deal of police backing. Raised $750 ($5,000 today).

Johnny Jones - Retired city employee and then in real estate. Raised $400 ($2,500 today).

W. W. Riser - Retired Leon High teacher and coach. Raised $100 ($750 today).

On the money front, Houston brought in more than she’d managed in 1973; taking in $950 ($6,400 today). Her fundraising network expanded from 1973 considerably. She had a great deal of support from from university staff and small dollar donations. While Tucker and Hirsch raised the most money, that success led to them having to answer for concerns they’d be beholding to the major developer interests of the city.

The race, just a few weeks long in total, was widely seen as a quiet affair. There were no major issues dividing the candidates at the time, with much of the debate focused around things like widening of roads and development regulation. All candidates agreed on the desire for what would eventually become the Leon County Civic Center, with the only minor debate about financing methods and profitability. Others differed on if I-10, which was going to go through the county North of the then-city limit, should have a “spur” that had a lane go right into downtown. None of these issues or “divides” captured the public. The Tallahassee Democrat decided to not even endorse anyone, but rather faulted the short campaign timetable.

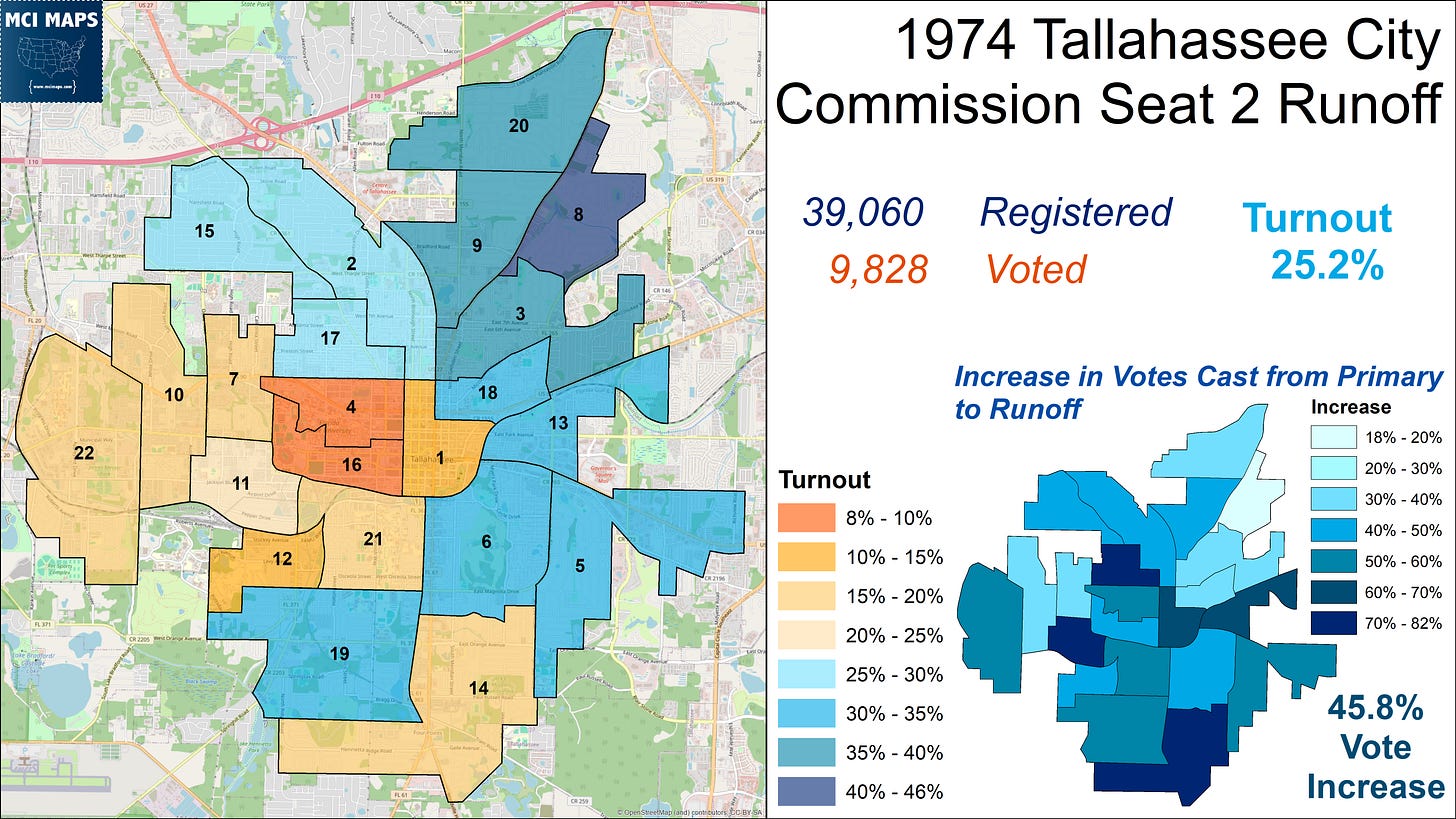

The result of the crowded field and lack of major issues was a drop in voter interest. Turnout would only be 17%, down 12 points from the 1973 contest. Voters it seems opted to wait for the field to narrow before tuning in. The turnout was so bad that Florida Secretary of State Dick Stone argued the elections should be moved to the same time as Governor or Presidential contests. Likewise the Leon Democratic Executive Committee also advocating for moving the dates. The dates would not move for decades, FYI.

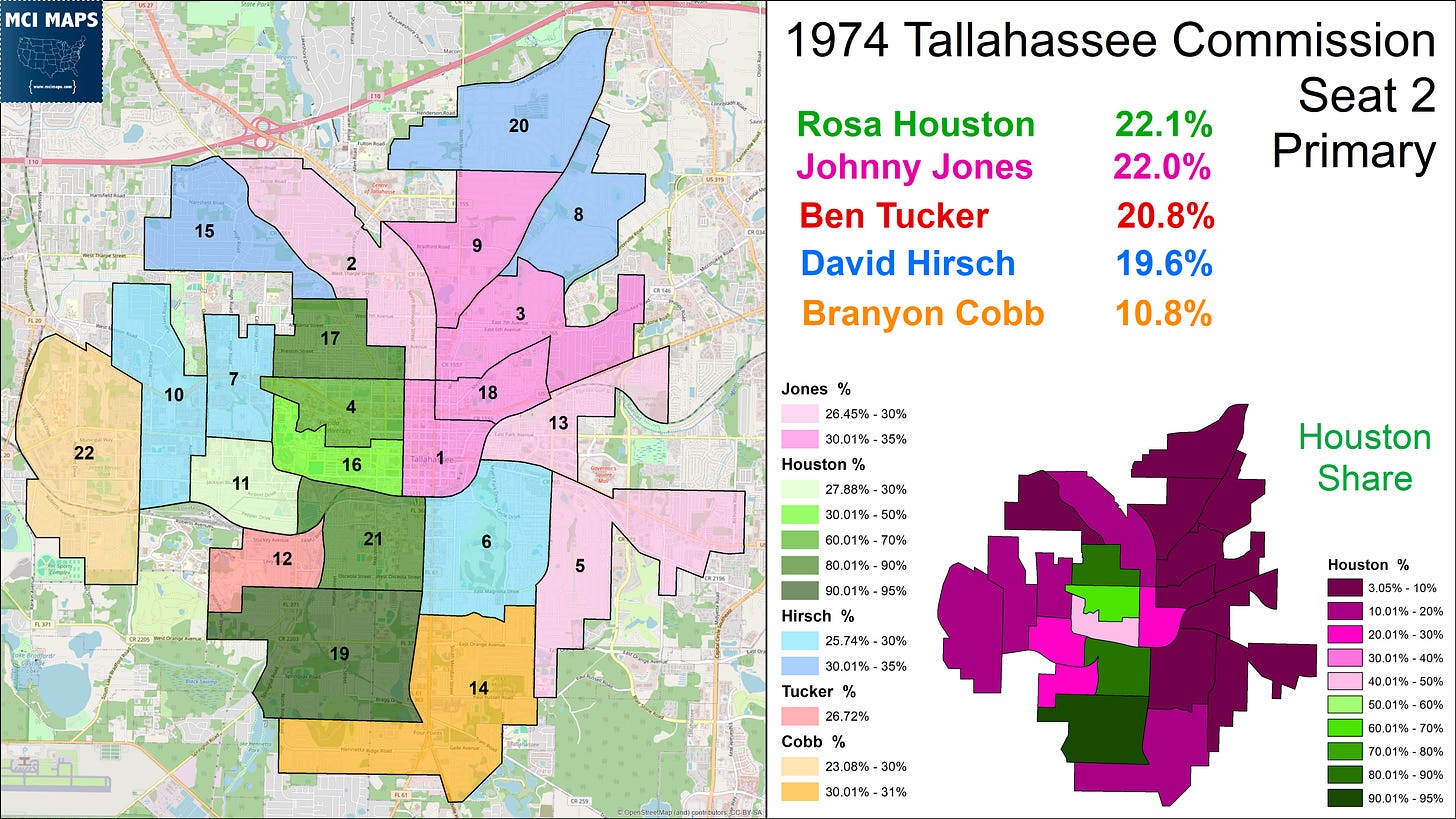

The results for the primary were a near 4-way tie, with only 175 votes separating the 1st and 4th candidates. Rosa Houston and Johnny Jones would advance to the runoff, with just two votes between them!

The precinct map is a colorful patchwork of candidate bases. Houston’s first place was thanks to absolutely dominant performances in the city’s Black community, taking over 80% in a 6-way race. She was also very strong with student groups.

While Houston was the candidate of student and Black voters, Jones was the candidate of what he dubbed “old Tallahassee.” The precincts in the east end of the city, but not as the newly-expanded borders (like precincts 8 & 10), made up many of the families and neighborhoods that were major players in Tallahassee politics going back decades. Jones, as a retired city employee who was civically involved, had stronger name-ID with these very residents, helping him make a runoff despite little cash.

With the primary results, the biggest funded candidates were out! Unlike 1973, where Houston came in 3rd and missed the runoff, this time she had her ticket to keep going.

The Runoff Controversy

The primary results meant a runoff would be held just one week later. Candidates only had 24 hours to raise any funds for said runoff, a timeline so short that calls for changes to the calendar also emerged. Houston beat Jones in that short fundraising window, taking in $600 to Jones’ $270. Much of her support came from university staff.

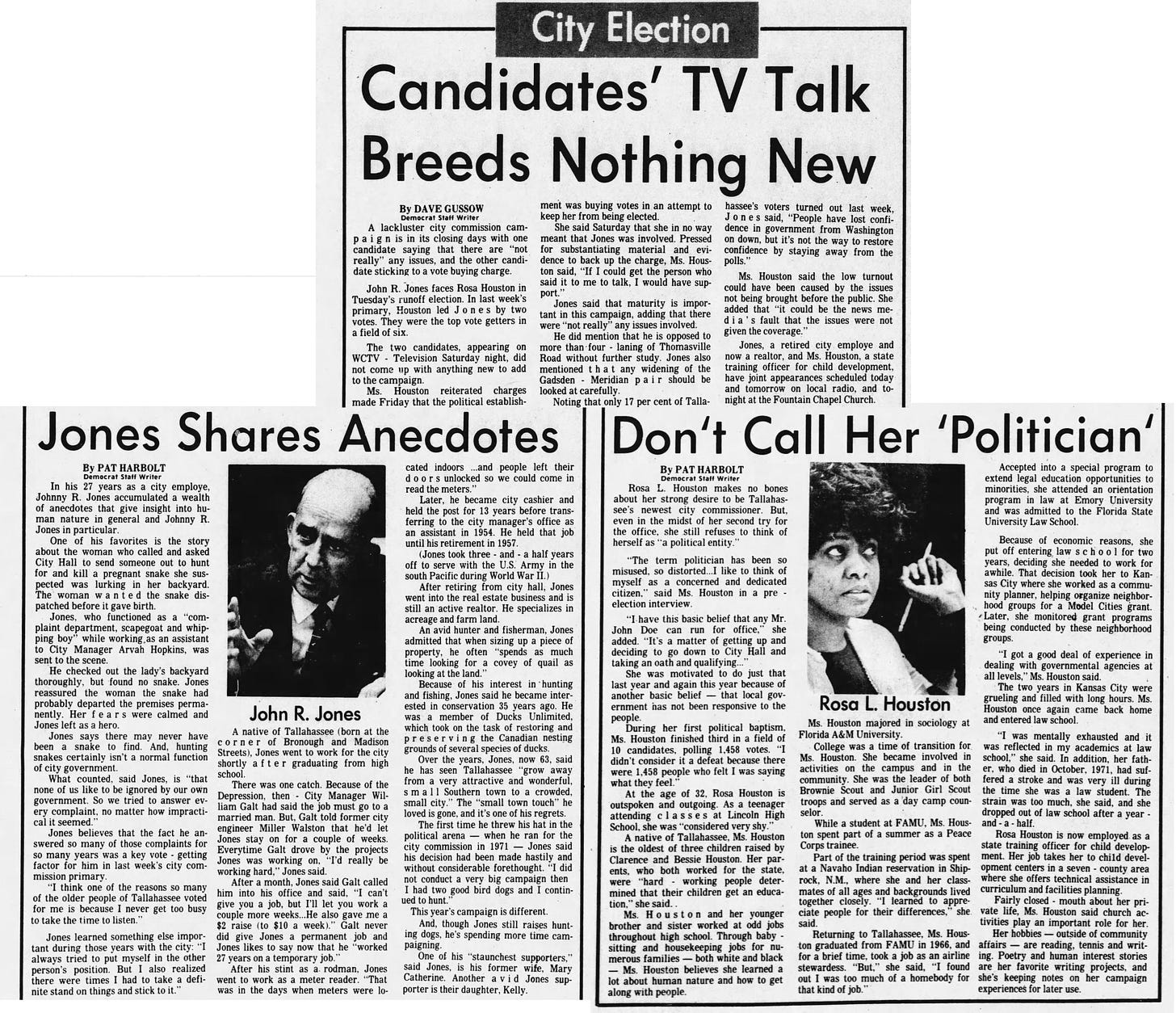

The short runoff campaign, like the primary, saw no major city issues discussed. The candidates agreed on much. However, drama did emerge in the runoff when Houston laid out a charge about vote buying. The details are laid out below, but Houston stated that she was warned an effort was underway to buy votes if needed to ensure she did not win the runoff. It should be noted Houston made it clear she did not think Jones was part of it, but rather this was a scheme by the conservative establishment of the city.

Now, if you read Issue 5, and have gleamed from this piece, I am a personal fan of Houston’s advocacy and issue positions. I also have no doubt the entire Tallahassee establishment did not want Houston to win. Jones was not the establishment pick in the primary, but no doubt the big players in the city could work with him vs her. However, in fairness, I think leveling this charge was a mistake. No major evidence emerged and with Houston unable or unwilling to name who told her the plot, she wound up coming off conspiratorial. Remember, Houston was a well-regarded administrator heavily involved in public and government affairs before her 1973 run. She was not a crackpot. However, she demonstrated her political naivety here, bringing up a charge she heard but unable to prove. I also cannot rule out that the combined stress of the campaign plus maybe some vague warnings led to an overblown reaction. I say this because again the conspiratorial accusation does not square with her history to that point. Something went amiss here. Either way, the result was a broad condemnation that I don’t think played well outside of those already supporting her.

The vote-buying issue aside, the coverage of the race largely focus on candidates personally. On this, Jones relied on his longtime ties to the city, but notably working for the city in non-powerful positions. His anecdotes of being a roadman, meter reader, and complaint department worker, definitely did not give off “insider vibes.” Houston was likewise an outsider, but rather than focusing on personal stories, she discussed broad issues and challenged the city to do more.

The problem for Houston in this context was that the city at this time definitely preferred Jones’ humble and quiet approach (which I’m not knocking) to Houston’s more aggressive advocacy. Jones would constantly emphasize his “maturity” in the runoff. How much of a personal dig that was supposed to be at Houston, I cannot say, but it certainly aided his cause for city voters who didn’t want to “rock the boat” in any big way.

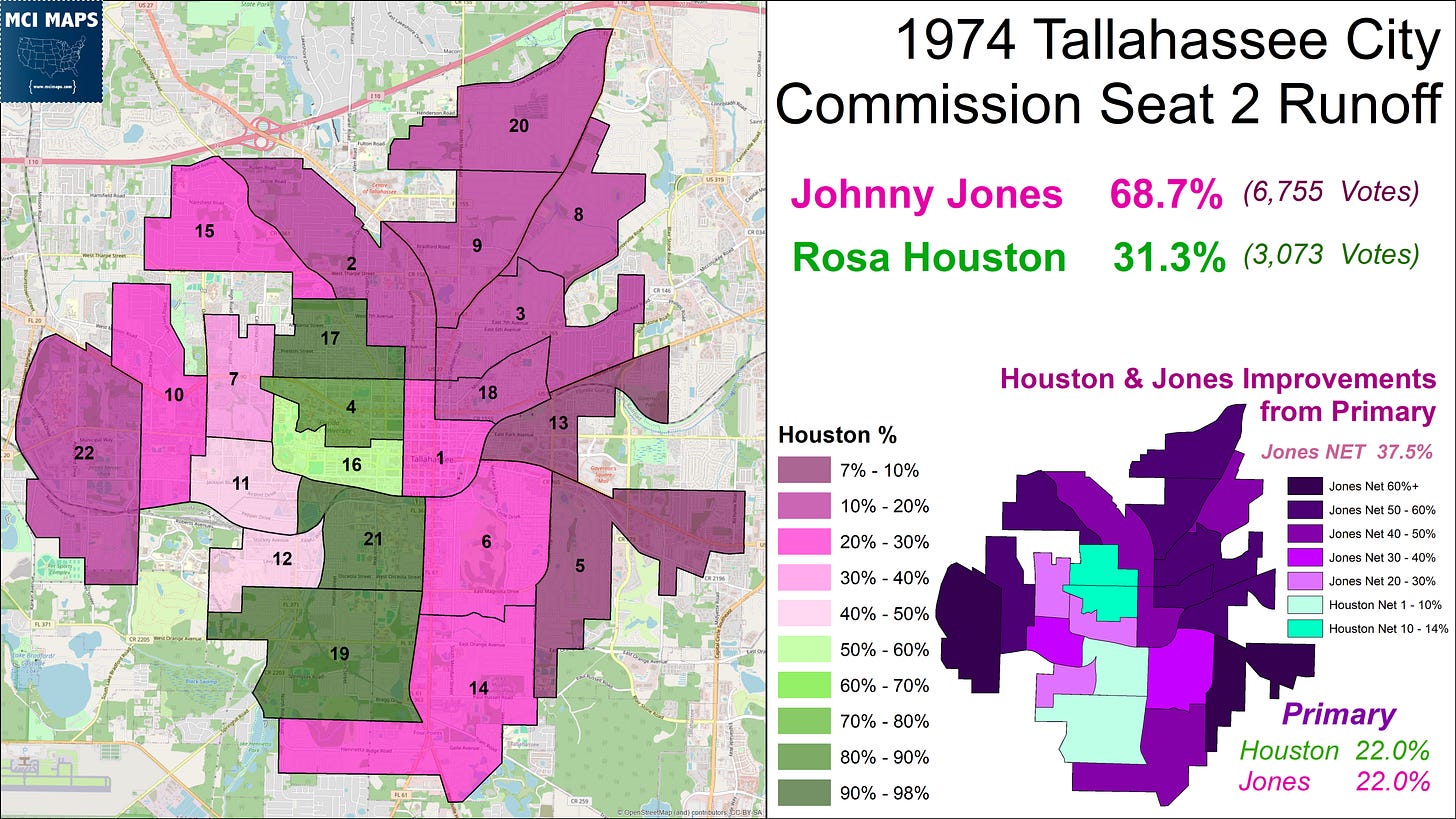

When the results came in, Jones easily took the election, pulling in 69% of the vote to Houston’s 31%. Her support was largely Black voters and the students. She had little backing in the heavily white communities, especially in the east.

Between the primary and runoff, Jones made a NET vote increase of 38%, gaining more support than Houston across all precincts outside of Black neighborhoods and the campus. The net Jones increase in the heavily white neighborhoods topped over 50%! The divide is very stark.

Turnout was notably up from the first round, with 25% of voters casting ballots. The theory that the crowded primary left voters waiting for the runoff to winnow the field bore fruit. Turnout was strongest in the heavily white eastern neighborhoods, while under 10% in the student-heavy precincts.

This turnout dynamic is one major thing that would dog more progressive candidates. Houston’s best base had much weaker turnout. This wouldn’t have changed the winner here, but it could in much closer races. Of course one positive for the Houston coalition is that turnout went up alot in Frenchtown and around the campuses between the two rounds, closing some of that gap compared to the primary.

Retrospective and Looking Ahead

The vote buying scandal no doubt hurt Houston, but its also very hard to imagine she would have come close to winning the runoff either way. Houston’s support in the primary remained heavily clustered in the Black and student communities, with little white suburban support. This was the problem race still played in Tallahassee politics, specifically around a candidate so outspoken and progressive. Meanwhile, James Ford was re-elected unopposed that same day. That was enough “progress” for many.

Houston’s loss was not the end of her political story, however. She would remain active as always, being a fixture in Tallahassee politics well into the next decade. In 1975, she would make one more play for city council. I will cover that race, plus a renewed debate out moving to city districts instead of at-large, in my next issue. That issue will set the stage for a final dash of candidates in the late 1970s; leading into major transformations in the the 1980s.

I also am going to do a short supplemental that discusses some ballot drama from that 1974 runoff. A late-filed lawsuit over write-ins, Ford appearing on the ballot by himself, and Houston questioning ballot access. The debate and controversy will give me a chance to show how precinct analysis can answer disputes. That will come out soon, then onto Issue 7!

No idea when I will be done with this series…….