Issue #173: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 5: Rosa Houston in 1973

Advocating for a progressive government

Today is Part 5 of my series on black political power in Tallahassee, Florida. As many of you know, I have been working on a historic series looking at black candidates in Florida’s capital from the 1950s forward. This series tracks not only black political power, but the evolution of Tallahassee from a small conservative town into a diverse and liberal community.

The previous issues can be read here.

In Issue 3 I covered the election of James Ford, the first black commissioner since reconstruction. However, as I discussed then and will lay out in today’s issue, the city of Tallahassee was, at the time, still more hostile to outspoken black candidates. Ford’s win came with strong white support, aided by his residing in whiter communities and being perceived as “responsible and mature.” Many future black candidates, running on platforms around increasing aid to the poorer southside and Frenchtown communities, would be met with strong resistance from the whiter communities.

This political dynamic was at a time when Leon County was slowly moving away from its “Dixiecrat” heritage, but still was still influenced by southern culture. To further aid understanding of the region at the time, I wrote up this supplemental that looks at Leon County’s politics at that time. It is not required reading, but offers more context.

Today’s issue will look at the 1973 election, which featured Rosa Houston, the first black female candidate of that era. Houston would spend her political career advocating for the city to be more proactive in aiding poorer residents and responding to concerns in the black neighborhoods; most of which had seen stagnant growth thanks to the legacy of Jim Crow. This piece will show how little traction these issues had with the still moderate/conservative city.

The 1973 Campaign

In February of 1973, two city council seats were up for election. It is in Group II that I will be focused, as this is the seat Rosa Houston ran for.

So who was Rosa Houston? In 1973, Houston, then 33, was already a prominent local civic leader and activist. Houston graduated from FAMU, Tallahassee’s historically black college, and was at that point a teacher of education at Florida State University. She was the acting Director of Tallahassee Urban League and the President of Tallahassee Urban League Guild. She also chaired the Leon County & City of Tallahassee Human Resources Development needs study; which was formed to analyze the growth in the community and assess the needs of residents. By this point Tallahassee and Leon County were in a major growth spurt, fueled by state agency expansion and campus expansions. The city voter registration then sat at 30,000 - up 4K from just a year earlier.

Houston clearly was seen as a reliable administrator, hence her role in what are often overlooked but important organizations. On top of this, Houston was heavily involved in civic matters with day to day residents. One such example was lobbying for public Christmas lights for the Frenchtown neighborhood, which is historically black and poor, to match with displays in nearby downtown. For Houston, such a matter, seen perhaps as unimportant to most, was about giving the same quality to residents that others enjoyed. Houston would also be constantly writing letters to the editor and speaking on issues. Her name is all over the Tallahassee Democrat newspaper archives.

In 1973, Houston made the jump to running for office. In doing so, she spoke about the importance of increasing aid to the poor and discussed the equality gap that still existed between white and black residents.

Houston faced off with a large number of candidates, easily one of the most crowded races of the time. In total 10 candidates ran, but Houston’s major opponents were

Larry Brock - A CPA with the State of Florida

Mike Joanos - Prominent businessman

Earl Yancy - Insurance Executive

Thomas Miller - Prominent businessman

John Butler - Insurance officer and veteran

The issues around the election heavily revolved around managing population growth. In just the last few years, 20,000 new residents had arrived in the area. Proving nothing ever changes, TRAFFIC CONGESTION was a major issue. Concerns about how to balance out development also dominated discussions. A city well known for its lush green spaces and canopy roads, candidates of all sides agreed that development must not turn the city into one of the many “steel jungles” of South Florida. Below is a 1967 photo of the famous “canopy roads.”

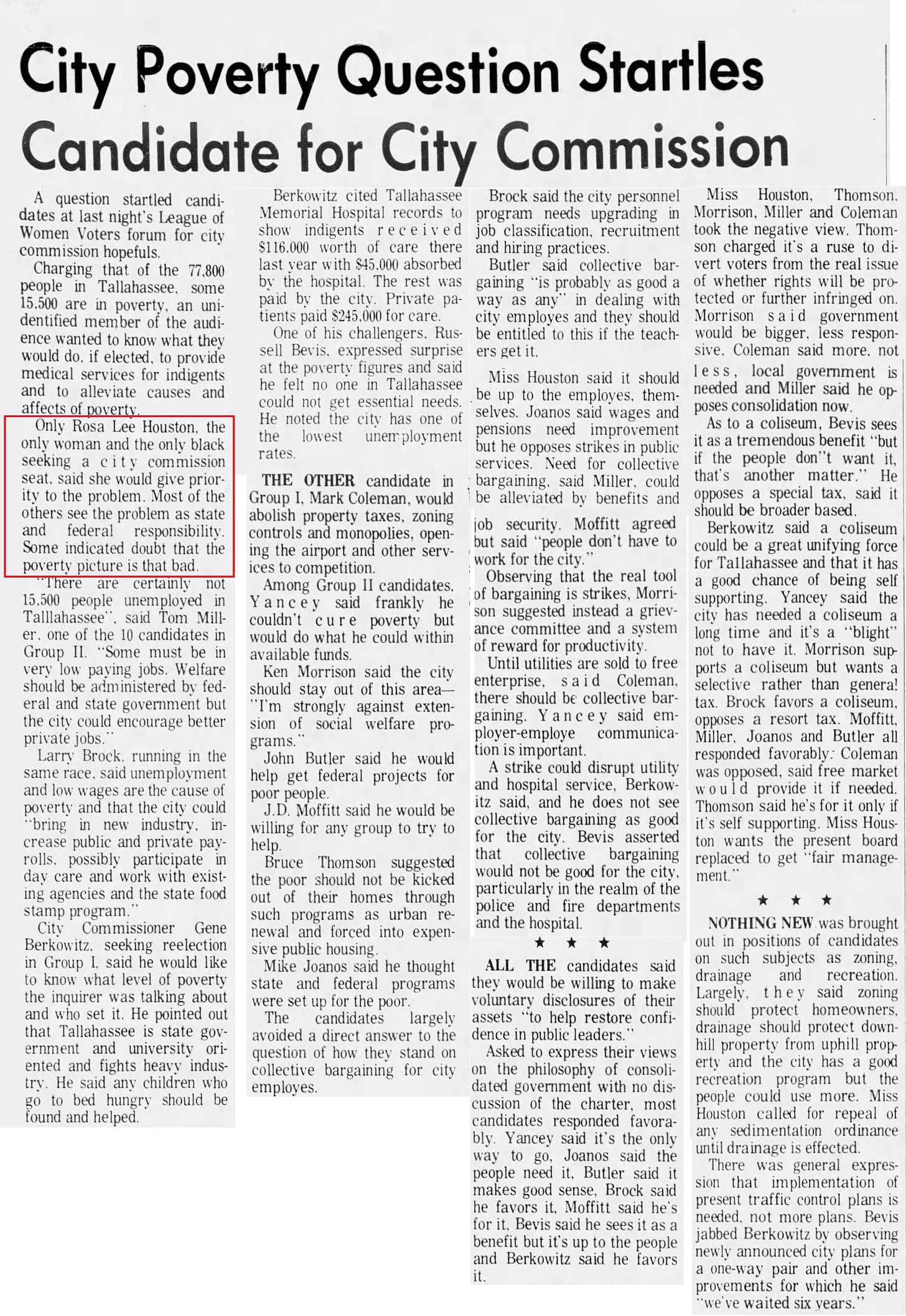

Candidates agreed on the importance of environmental protection while also improving infrastructure. The major differences were just a matter of how. However, as this news story shows, when broader social service issues came up, all candidates but Houston rejected the city being there for its poorer residents.

Houston was much more aggressive in pushing for federal partnerships to aid in social services for the poor. Her opponents, however, blew this off as the sole responsibility of the federal or state government. In this story, we see Houston taking on a much more proactive and progressive approach to government; something not really in line with the more moderate/conservative nature of the city at that point in time.

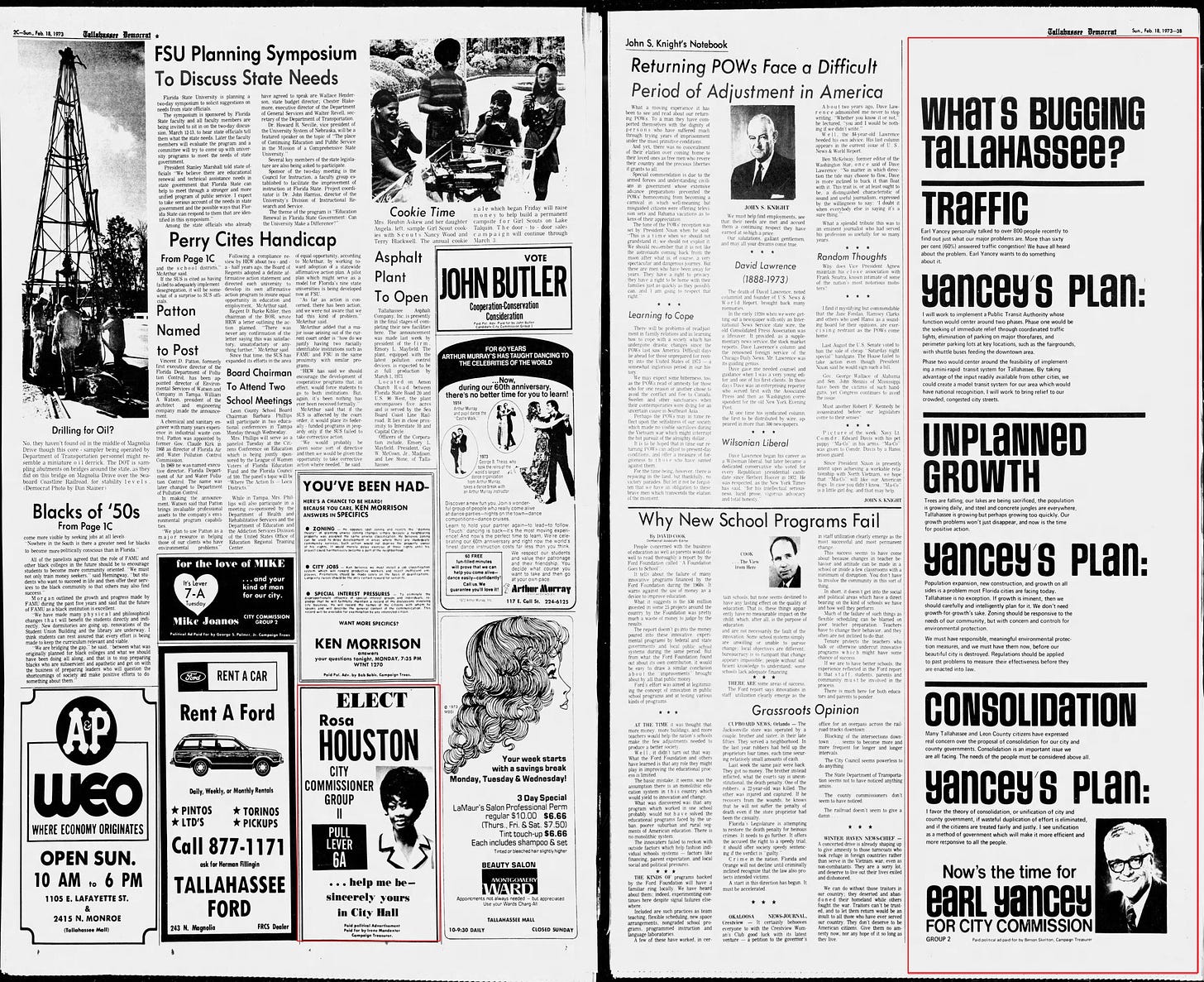

At this point, city elections were often only a few weeks of campaigning and were still low-money races. Adjusted for inflation, candidates were raising at max around $15,000 for their bids. In the primary contest, Houston was badly outspent. She only raised $215 dollar, which is $1,500 today. Mike Joanos topped fundraising with $1,900 - or $14,000 today. The fundraising gap naturally limited Houston’s visibility. A good highlighting of that is the advertisings done in the Tallahassee Democrat that year. See the comparison below. Houston had a smaller add while Yancey, who raised $1,300, or $10,000 today, has a full half page.

The crowded field and lack of funds led to Houston coming in 3rd, missing a runoff. However, her 3rd place still saw her outdo the most well-funded candidates. From a dollar per vote perspective, Houston far outpaced her opponents, spending only $0.15 per vote.

Earl Yancey, who secured the endorsement of the Tallahassee Democrat, came firmly in 1st place with 33%, followed by Larry Brock. While Houston did not advance, she did strongest in precincts A & D, which as I discussed in previous issues, were the most racially diverse precincts. Houston won precinct D, which was likely over 40% black, while getting virtually no support in the 90%+ white precincts B & C; which were still heavily dominated by older white families.

Houston was clearly the candidate of black voters, but had virtually no white support.

One week later, the runoff between Yancy and Brock was held. Yancy won with 56% of the vote, taking the heavily white precincts while losing the more diverse west end. However, turnout was much lower for the runoff in said precincts.

Clearly many of Houston’s backers opted to stay home in the runoff. As best I can find she did not make any public endorsement for either man, though clearly Brock was more of the choice for more diverse and “newer” Tallahassee.

Houston would not shy away from local politics after this loss. She would make runs again in 1974 and 1975, which I will be covering in Part 6. However, more developments took place in later 1973 that effected things moving forward, so lets discuss that real quick.

Election Changes

The 1973 City race was historic for one reason, it was the last held under the old election laws. As I discussed in previous issues, there was a separate voter registration for city elections at this time. Voters who wished to cast ballots for city races, in addition to needing to live in the city, had to register for city races specifically. First a voter had to be on the county roll, then register AGAIN for the city roll.

This always led to issues with voters who would constantly be casting their votes for President, Governor, or County Commissioner, would suddenly find out they couldn’t vote in the city elections despite being within Tallahassee’s borders. The new law from the legislature set the standard used today; register once and you can vote city races if you live in the city. In addition, this law led to the end of the city using the custom election precincts that differed from the county. Now the city elections would be held using the precincts drawn by the county, with the next elections having 22 precincts vs four. This increase in precincts makes neighborhood analysis much more effective.

That is something I will be delving even more into in my next issue.

Consolidation Referendum

After the February city elections and after the election law changes, Houston would be involved in another major political campaign. That November, the county would hold a vote on whether to form a consolidated government between Leon County and the City of Tallahassee. This was the 2nd attempt at consolidation following a failed 1971 referendum. At this time consolidation was a major debate point seemingly every year. It’s an issue that deserves its own supplemental that I may write up at some point. However, I don’t want to get too bogged down into it now. The key reason I discuss it here is because Rosa Houston was heavily involved in the anti-consolidation effort; operating as the spokeswoman for one of the anti-consolidation groups.

Consolidation was a very contentious issue from a government management perspective; with a great deal of debate around cost saving, overlapping bureaucracy, and representation. There was also a racial dynamic that revolved around the type of elections that would be held under a consolidating system. As I discussed in the Leon supplemental, the at-large county commission elections were not favorable to black candidates, leading to plenty of concerns from black leaders on what consolidation would mean representation-wise. In the 1971 referendum, which failed by 17 points, the black community was heavily against the proposal. In that campaign, a coalition of black and student activists joined with most incumbent politicians to oppose the effort.

Note the above, precincts 23 & 24 were over 90% black and were under 30% in support. Considering Ford had just become the first black city commissioner, the understandable worry was countywide consolidated elections would set representation backward.

One reform that aimed to bring black voters on board with consolidation in 1973 was to lay out that five commissioners would be elected at a district level and two at-large. Draft proposals said a single-member hence district could be drawn that was over 30% black; far more than the county or city were at that time. This did aid concerns about representation.

That said, support or opposition didn’t fall along racial lines directly, with white and black residents supporting or opposing for a mix of reasons. This time, though, consolidation did much better in the black community, winning 2 of the 3 majority black city precincts, though the black population in rural Miccosukee (northeast) were a hard no.

Consolidation failed that year thanks to strong resistance outside the city. Pro-consolidation leaders lamented poor city turnout as the main driver. That said, the hard opposition from the non-city voters would have made consolidation a very contentious affair.

The vote did pass in the city by a fairly comfortable margin, far different from the 1971 vote. This would put Rosa Houston at a disadvantage in future runs. Her push on the issue was not revolving around race, but rather how truthful the claims of immediate expansion of city services could be implemented. Again much of the debate was technical. That said, city voters had backed the proposal.

Looking Ahead

In Issue 6, I will look at Houston’s 1974 and 1975 campaigns. Houston would continue to find a chilly reception for her agenda, but she would still be setting the stage for candidates to follow.