Issue #159: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 3: The Election of James Ford

Modern Tallahassee's First Black Commissioner

Today I have Part 3 of my series on racial representation in Tallahassee. This is a series I am doing covering the efforts of black leaders to win elected office in Florida’s capital city. My last two articles have covered the following…..

Part 1: Tallahassee in the Jim Crow era, and the first black candidate for city council post-Reconstruction

Part 2: Tallahassee amid the Civil Rights Movement and black candidate attempts to win seats

At the end of the last issue, Tallahassee was seeing a growing number of black candidates for office. Debates about the racial makeup of the city based around annexation of different communities also became a major hot button topic. While the city remained much smaller than it is today, annexation and growth of the universities and state agencies meant the population now hovered around 80,000 to 90,000 people. The city still remained much more racially conservative than it is today, but outright segregationist sentiment was slowly declining.

Today we pick up in 1970. This piece will cover just the years 1970 and 1971, but this is an important moment, because it will make the first time the city elects a black commissioner.

Lets dig in

The 1970 Campaigns

In 1970, two of the city commission seats were up; with both incumbents facing a large field of challengers. This was a groundbreaking year, as both races saw black candidates file. In the Group I contest, Joseph Franklin, a FAMU graduate working for IBM, challenged incumbent Gene Berkowtiz. In Group II, John Norwood ran against incumbent Spurgeon Camp.

By this point the registration in Tallahassee was around 28% black (exact figures are frustratingly hard to come by).

The race coverage largely focused on utility rates, possible consolidation with the county, and investment in entertainment venues, namely an expanded coliseum. Commissioners Camp and Berkowtiz were considered part of a newer generation of leaders. Notably both supported the straw poll on re-opening the public pools with integration in 1967 (I discussed that fight in Part 2).

The Tallahassee Democrat newspaper praised both incumbents while offering other alternatives. However, the paper went out of its way to cast dispersions on both Franklin and Norwood.

The final line about Norwood not being good for representing all the city is especially egregious. Nothing in the coverage I found indicated Norwood was anything but a man who once or twice referenced the desire for all citizens to feel presented - a clear point about the lack of black commissioners. This issue of bias on racial matters from the newspaper will be discussed more in my 1971 section further down. I think that editorial was out of line then and has only aged worse. Evening specifically dedicating a headline titled “The Two Negroes” demonstrates a clear passive racism; even if not hyper hostile.

The first round saw both Norwood and Franklin advance against the two incumbents! In the Group 2 race, Norwood actually finished in first, though notably both black candidates had very similar shares of the vote. This was history making, as it meant two black vs white runoffs at the same time in city history.

The one week campaign for the runoff led to a flurry of interest and expected record turnout.

The runoffs saw both Berkowtiz and Camp surge from the first round shares to secure fairly comfortable re-elections. Franklin and Norwood improved a bit from the primaries, but clearly white voters consolidated. The election, like those before, broke down between the racially-diverse west and the heavily-white east.

These results were another example of black candidates running, unable to get past racially-polarized voting, and being maligned in the press. Yes this was less hostility than seen in many other cities, but it still was a major problem. Black voters were growing increasingly frustrated with the state of things.

The Historic Election of James Ford

After several years of black candidates trying to win a post on the city council, Tallahassee would finally break that barrier in 1971. That year, James Ford would run for an win a post on the commission, becoming the first black man to do so.

The 1971 contests saw two incumbent commissioners up; George Taff and W.H. Cates. These were both the commissioners you will remember from my last article that voted against putting the pool integration straw poll before the voters. Both represented as older school of officials, with Cates being the longest serving commissioner in history to that point. It was in the Cates race, officially “Group 2” for that year, that James Ford opted to run. Ford was already a history maker at this point. He was the first black assistant principle of Leon High School, having been a teacher and the first black drivers education teacher. In a still-modest-sized city at this point, Ford’s connection to a school based in the eastern white communities made him a much stronger candidate who could get the needed crossover support from white residents to win.

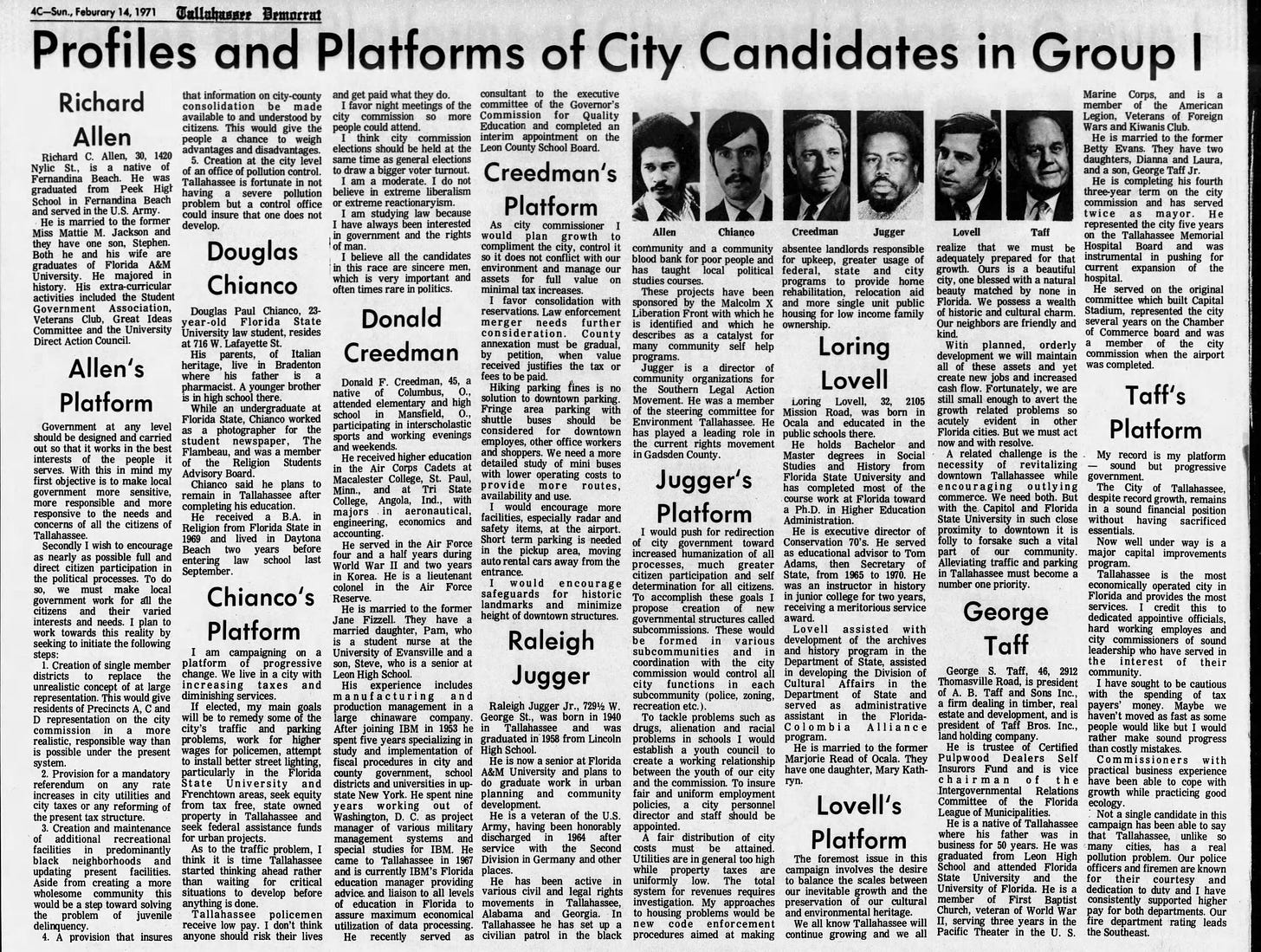

Ford would face off against Cates and 3 other white candidates in the primary. Bio and platform details can be seen below.

All candidates focused on issues of the city’s growth. Ford waded in on one notable issue of race - and that is the debate over consolidating the city with the county. The issue was a major discussion point at this time, and a referendum would come a few years later. Ford addressed the issue that consolidation plans would keep the elections at-large; which risked the black community being overlooked even more so than it already was. That idea gave black residents major concerns, and they insisted on districts being used if consolidation happened.

The Group 1 contests are also important to discuss in the context of Ford’s election. That seat, which had incumbent George Taff running against five opponents, had two black candidates running; Richard Allen and Raleigh Jugger. Both Allen and Jugger were younger men than Ford and heavily involved in civil rights and activists for the city’s black residents. Allen spoke about turning the city into single-member districts, articulating a point that was growing within the city’s black community. At this point, the inability of a black candidate to win office was becoming a growing grumble, and the 1965 Voting Rights Act could leave the city open to a challenge over its at-large system.

Both Allen and Jugger spoke for voters who had yet to be truly represented in city hall. However, their outspokenness was going to be a turn off not only to the local press but a large majority of the white voters. Taff was vulnerable, like Cates, with both being seen as out-of-step with changing times. However, the strongest threat to Taff was Loring Lovell, a state employee with a major focus on environmental presentation balanced with urban growth.

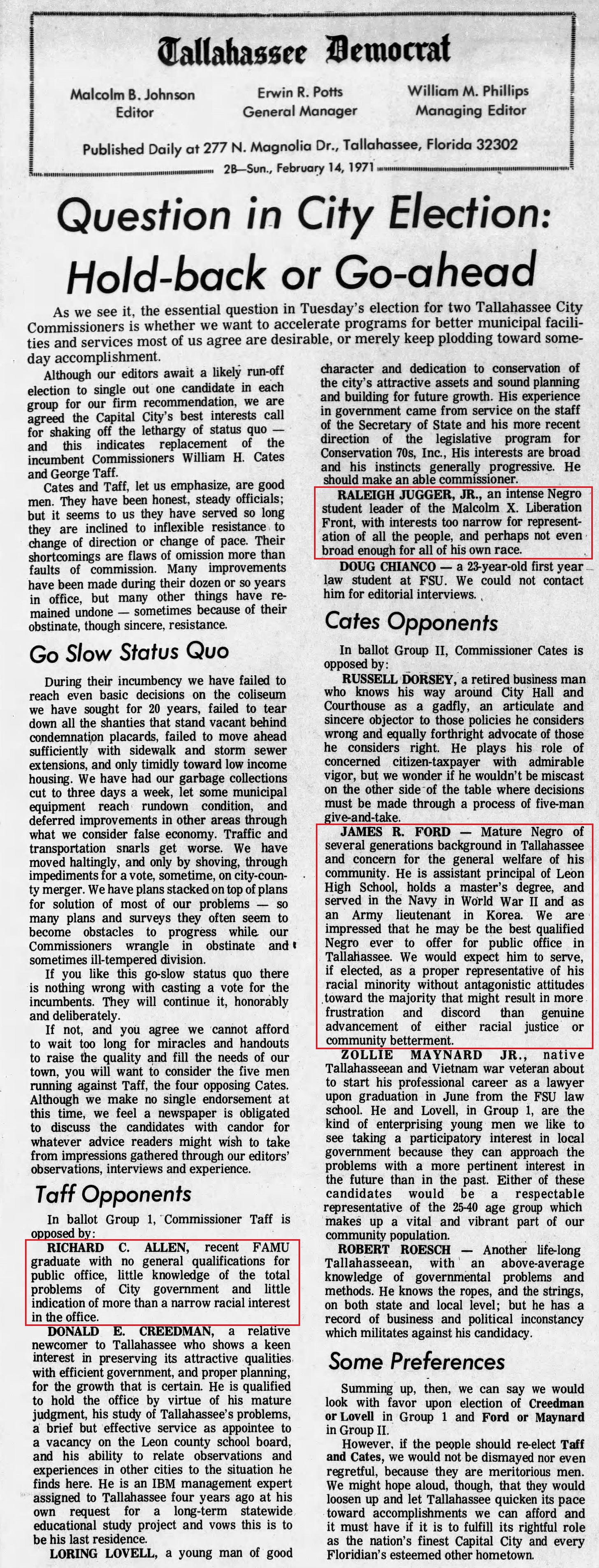

Local press coverage mattered a great deal here. I have discussed before the clear bias at times demonstrated against black candidates considered too “outspoken” or “militant.” This came from the sentiment of editor Malcolm Johnson. The coverage of Allen, Jugger and Ford, can be seen below.

Even in his praise of Ford, there is still a notable racial stigma. Ford is the “mature Negro.” Meanwhile. Allen and Jugger are “intense” and don’t know what they are talking about. Johnson’s words can be incredibly infuriating to read, but he very likely reflected the white majority of the city at this point.

On February 16th, voters went to the polls for the city primary. In the Group 1 contest, Loring Lovell advanced with George Taff, while in Group 2, James Ford advanced with W.H. Cates. Both incumbents easily led, and it would not have been shocking if both won their runoffs. However, while past incumbents had been able to consolidate support, especially in the 1970 contests, there was a growing sense within the city for changing members. Here I also was able to get the racial breakdown of registration by precinct - though not this is not the final vote cast.

The precinct table below shows the divide within the city.

Ford was strong in the more diverse west, but got just 15% in the whiter east, similar to past black candidates. In the Group 1 contest, however, we can see how little support Juggar or Allen had with those white precincts. Both men also did not managed to consolidate as much white liberal backing as Ford had. Combined they still would have lost precinct A, and only carried precinct D with 37%. Lovell, meanwhile, seemed to have support crossing moderate and liberal voters; doing fairly evenly across the precincts.

The runoff, just one week after the primary, set the stage for two runoffs that pitted older and more moderate incumbents with younger challengers. Both incumbents reflected a more cautious conservatism, while their younger challengers represented youth and a forward-thinking mantra.

Here, the coverage of the Democrat comes into play again. Just days before the runoff, Tallahassee Democrat Malcolm Johnson wrote this opinion piece. The article is filled with passive racism that questions black activism and comes off very paternalistic. At the same time, it also lays out the challenges Ford faced running for office in a city majority white and where he wouldn’t be safe going door to door. It praises Ford and encourages voters to back him. It very much reflects the sentiment of whites at the time - “sure equality, but lets all be respectable now.” This can be frustrating to read (it was for me) - but Ford himself credits THIS piece with helping him get elected.

Johnson, to his credit, does not hide the racism in the city. He points out many white businesses and leaders worry about openly supporting a black candidate. Johnson does not pretend the city is a racial egalitarian place. Johnson’s last line has been quoted many times in the decades since.

“We’ve been saying we’d elect a ‘good Negro’ if one ever ran. Now here’s our chance to prove we aren’t hypocrites”

This is of course an extremely racist and insulting thing to say about past black candidates, but Johnson almost surely spoke for the white majority of the time. He just said it out loud.

On February 23rd, history was made, with James Ford and Loring Lovell winning their runoffs for city commission.

Ford and Lovell won thanks to big wins in the more racially diverse west, but also strong showings in the eastern neighborhoods. Lovell outperformed Ford in the white suburbs, but Ford’s 40% in both precincts B and C were record shattering for a black candidate. Ford could not have won without these strong eastern showing; something he credits to both the op-ed, but also the support his students gave in encouraging their older parents to back Ford, the man they knew from school.

Looking Ahead

Ford’s win was a groundbreaking moment for the city of Tallahassee. The commissioner would serve through the 1970s. His election also ended any major chance of Tallahassee being divided into single-member districts per a voting rights act lawsuit. It has been pointed out that what also aided Ford’s win was white leaders realizing that risk, and finally pulling the trigger on electing a black candidate. There is likely some truth to this, though Ford’s win would have been impossible if white voters were not comfortable with him.

Through Ford’s tenure, he’d get along with white leaders well, so much so there would at times be tension between him and the black community. Debates about race and communities getting the attention they needed would not die with Ford’s election. As Ford sat on the council, another generation of black candidates would run, seeking to unite a growing liberal white, student, and black population. More black candidates would run, eventually more would win, and the makeup of Tallahassee would continue to evolve.

Part 4 will be out soon, in the next week or two. I plan to cover the later 1970s races, which then set us up for a major sea-change in the 1980s with a new voter coalition.