Issue #157: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 1: The Reverend vs the Segregationist

Racial politics in Florida's capital city

Today’s article is the 1st issue of series that will be coming out this week on black representation in Tallahassee. I plan to track the path of black commission candidates in Florida’s capital city; starting with elections in the city’s small Jim Crow era, and ending with the city’s expansion and growing progressive posture.

Today Tallahassee is a very liberal city, heavily democratic, and with a long history of electing black and white city commissioners. Tallahassee and surrounding Leon County are now seen as a blue island in the panhandle’s sea of conservative red. However, right after WWII, Tallahassee was a small town; fitting right in with the culturally southern Florida panhandle. This made the path to black representation a long struggle. My goal here to to cover that fight.

Lets start with Part 1: The 1957 Election and the first black candidate since reconstruction.

Tallahassee’s History and Politics

I have covered Tallahassee and Leon County political history a few times, so I won’t repeat myself a great deal. I do want to highlight some important points and reference some other articles. You can read more I’ve written on Tallahassee and Leon Politics here

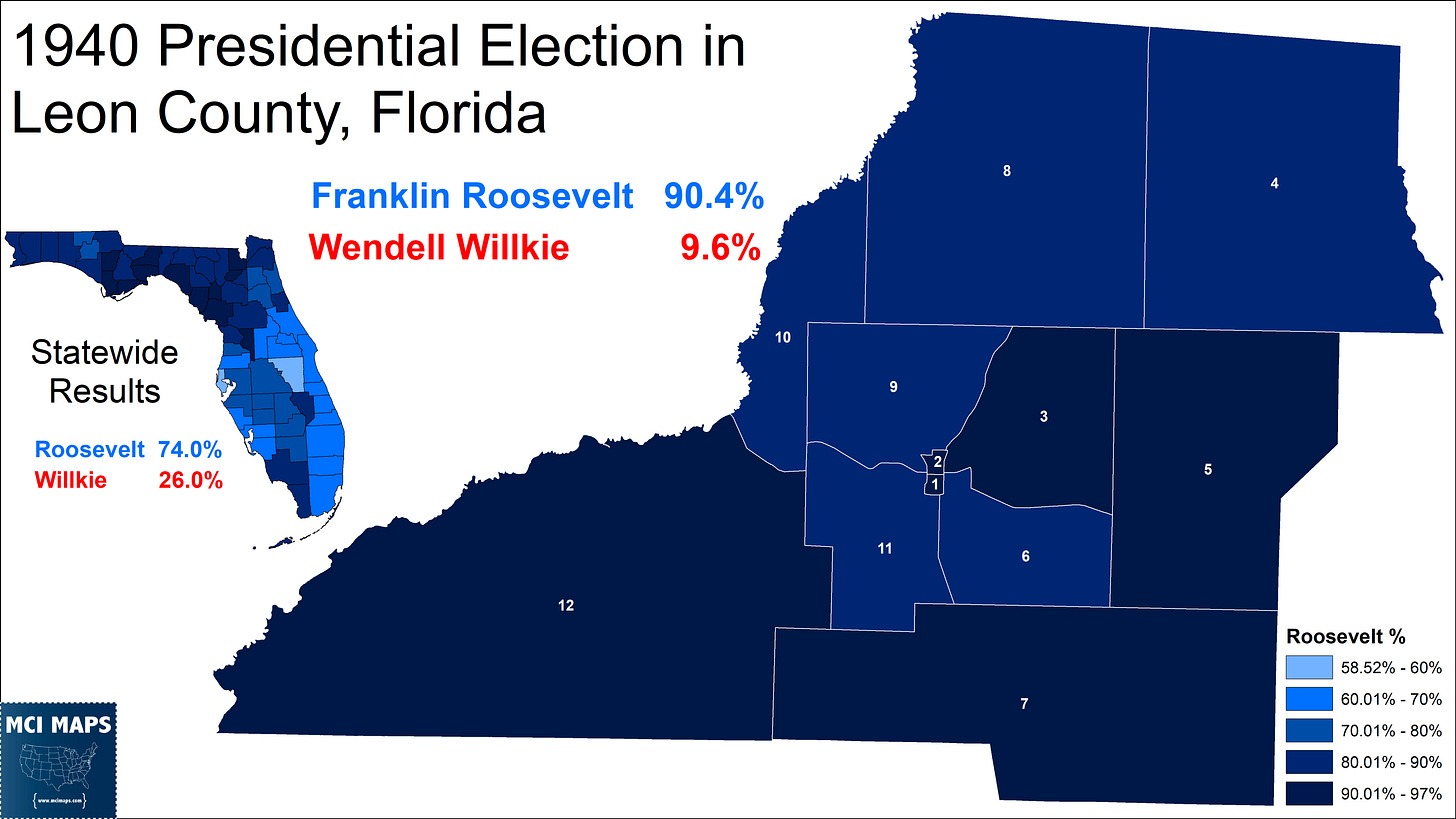

In the post Civil War era, Leon County had a very large black population. The county was the site of many plantations, and when slaves were freed after the war, early Reconstruction Elections saw Leon with a majority-black voter roll. Like the rest of the south, this era of black political power would not last and eventually be violently suppressed by Jim Crow. Through the early 20th century, Florida would be like any other one-party Democratic state. In 1940, a time when the county voter roll was almost entirely white, Franklin Roosevelt took 90% of the Leon County.

The mid 1940s and early 1950s would see major shifts in voter registration. I delve into this in my 1945-1950 voter registration article, but long story short, the efforts of the NAACP and elimination of white’s only primaries saw the Leon voter roll go from being just 5% black to over 15% black. A vast majority of the county’s black voters were still not registered, but they were beginning to flex their muscles. In 1956, black voters in Tallahassee swung to Ike Eisenhower after Democrat Adlai Stevenson continued to try and appeal to segregationists. As a result, precincts 9 and 11 in the county, where large black voter groups were, swung heavily to the GOP.

By the mid 1950s, Tallahassee and Leon County had a black population beginning to come into political power, but the area was firmly in the control of white leaders. These leaders were, by and large, not the type of George Wallace rabid segregationists, but levels of paternalism and racism absolutely were on display. This was the dynamic in the county when Tallahassee voters went to the polls in 1957.

The 1957 Tallahassee Commission Campaign

The first time an African-American opted to run for Tallahassee commission in the post-reconstruction era was 1957. This election, held in February of that year, came just as the city was reeling from its well-publicized bus boycott.

The Bus Boycott of 1956

Like much of the south, the city busses were segregated at this point. Then, in May of 1956, two black female Florida A&M students, Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, sat down in the white’s only section when the black section was full. They refused to move and were charged with "placing themselves in a position to incite a riot." The Dean of Students bailed them out. This then led to the Ku Klux Klan burning a cross in one of the woman’s yards that same evening. A boycott, led by Reverend C.K. Steele, pastor at the Bethel Baptist Church, was formally organized with major student backing.

Leaders formed Inter-Civic Council to organize efforts and set up carpool services to get folks to work. The group was fined over $11,000 from the city for operating illegal carpools. However, the boycott financial hurt the city bus revenue, forcing shut downs and cutbacks. The boycott continued through the year, with white agitation against black residents growing. More cross burnings and gunshots at Steele’s house were recorded. The Klan held a march outside Steele’s church one day. Governor LeRoy Collins, a racial progressive for the time, who while apprehensive about the boycott at first, deplored the intimidation and violence. He would eventually suspended city bus services.

Just before the boycott began in the summer, Collins had secured the Democratic Primary for another term in office; with segregation issues being a major topic in the wake of Brown v Board. Collins was challenged in the primary by Lt Governor Farris Bryant, former Governor Fuller Warren, and Florida National Guard Brigadier General Sumter Lowry. Collins was the most racially progressive while Fuller Warren had denounced the Klan in his term as Governor. Bryant rant as a moderate conservative, warning against moving too fast on integration while Sumter Lowry ran as a far-right candidate who’s only platform was enforcing segregation. Lowry came in 2nd statewide, winning many surrounding panhandle counties, but came in dead last in Leon County.

The results in Leon in the primary showed the county was not as rabidly segregationist as many of its neighbors, but as we will see, this was often more of a “polite” discrimination. Yes there was white supremacy, but it was “respectable” - as city leaders saw it.

In December of 1956, the boycott formally ended, with a January 7th ordinance passed that repealed the segregation of the busses. Black drivers were also hired. However, the lack of racial segregation was replaced with an assigned seating system that still allowed for a driver to segregate the bus at will. This led to some black residents refusing to return to the busses. However, that system would eventually also give away as a bi-racial commission set up by Collins took it to task.

This was the tension in the city that existed when the Reverend King Solomon Dupont decided to run for city commission.

The Dupont vs Atkinson Race

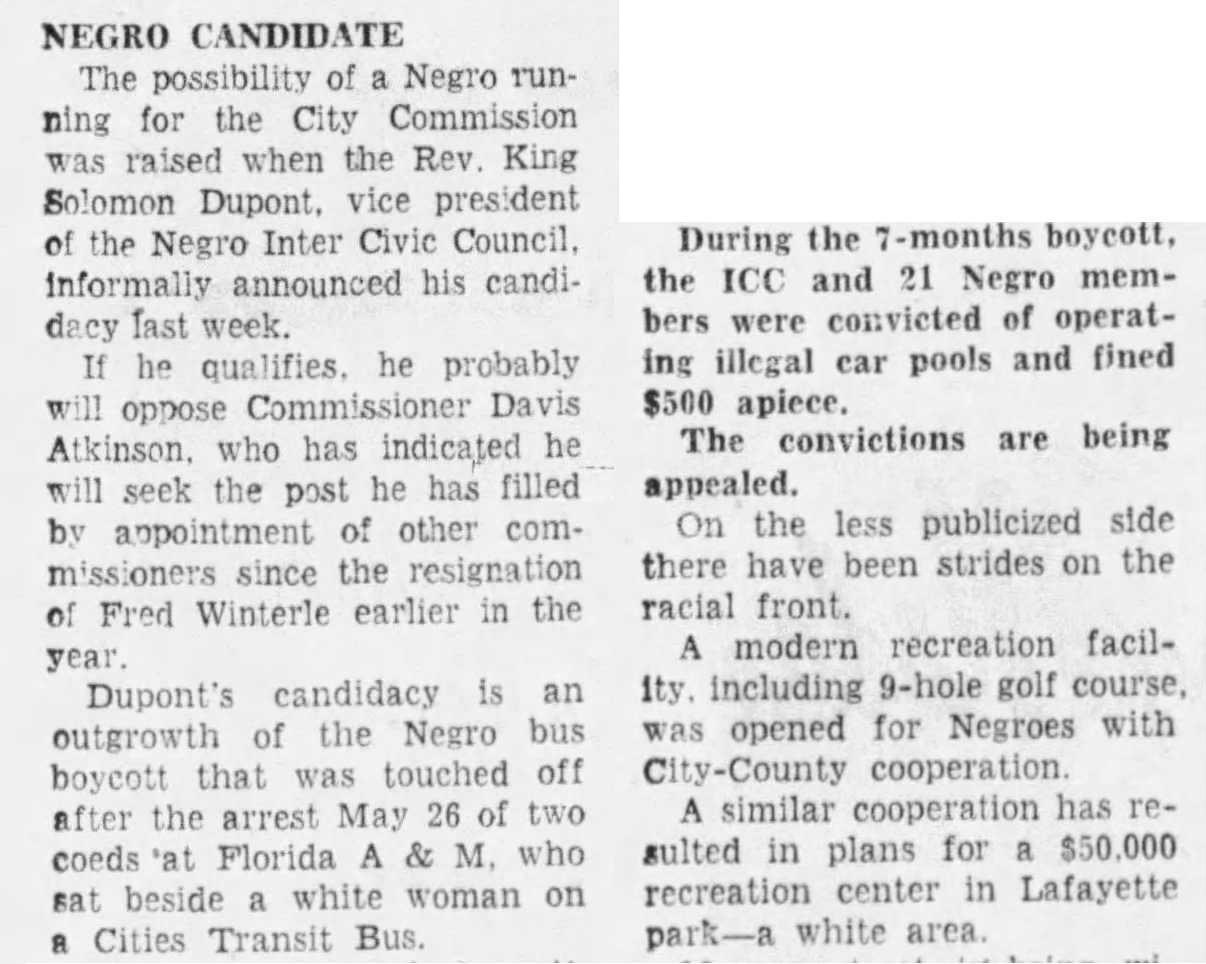

Campaigns for Tallahassee office at this time were very short. The city was around 48,000 people in total with under 10,000 votes cast for city races. The city at the time was much smaller than today and very close-knit. In December of 1956, just a few months before the election, Rev King Solomon Dupont made his intentions clear that he intended to run for a commission seat.

Dupont, the grandson of slaves from Virginia, was one of many leaders in the civil rights movement in Tallahassee at this point. He was the Vice President of the Inter-Civil Council that had been heavily involved in the bus boycott. He was a longtime minister while his wife taught at Lincoln High School; who’s job was often threatened due to her husband’s advocacy.

The notion that a black candidate would run for office struck the local press and populace with surprise and some apprehension. Tallahassee was segregated and conservative at this time, but not viscously violent like other parts of the deep south. However, as the bus boycott had shown, tensions could lead to violent threats or acts. Though the Tallahassee boycott was less violent than in other states.

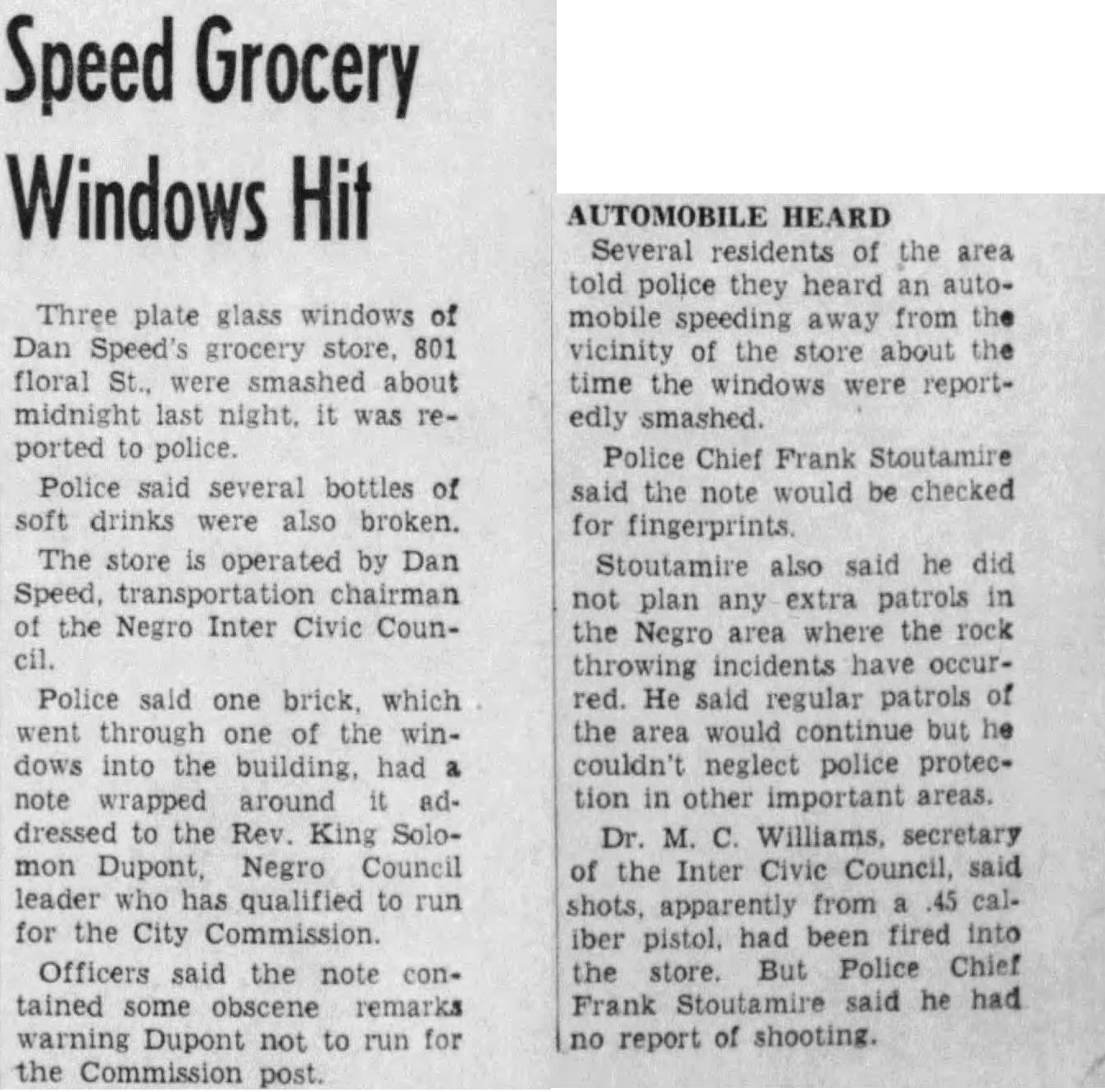

The tension = violence was seen when a grocery owned by a boycott leader had a brick thrown through its window with a note decrying Dupont’s candidacy.

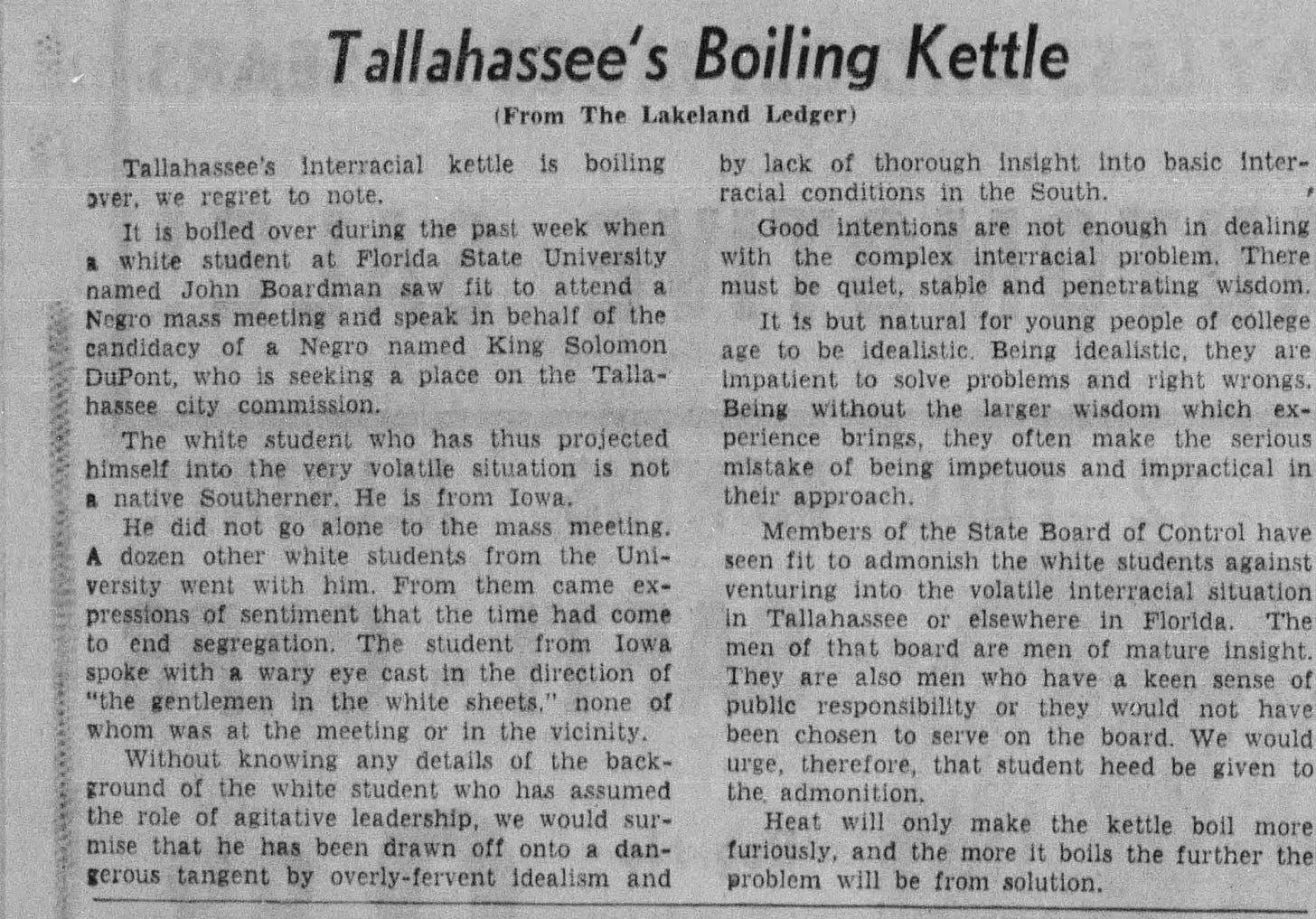

The local press clutched its pearls about agitation from the boycott and racial progressives. A story in the local paper discussed the efforts of a white student from Iowa who spoke up for Dupont’s candidacy. The paper did not take a pro-segregation position, but rather a “hey lets be careful and slow” position.

Good intentions are not enough in dealing with the complex interracial problem. There must be quiet, stable, and penetrating wisdom"

The paper was right that the move for equality would be met with violent reactions from the Klan and its sympathizers, but like so many of the time, it put the blame on those seeking equality. Calling segregation “complex” is indicative of the attitude of whites at the time. Not viscerally hateful, ala George Wallace, but paternalistically condescending.

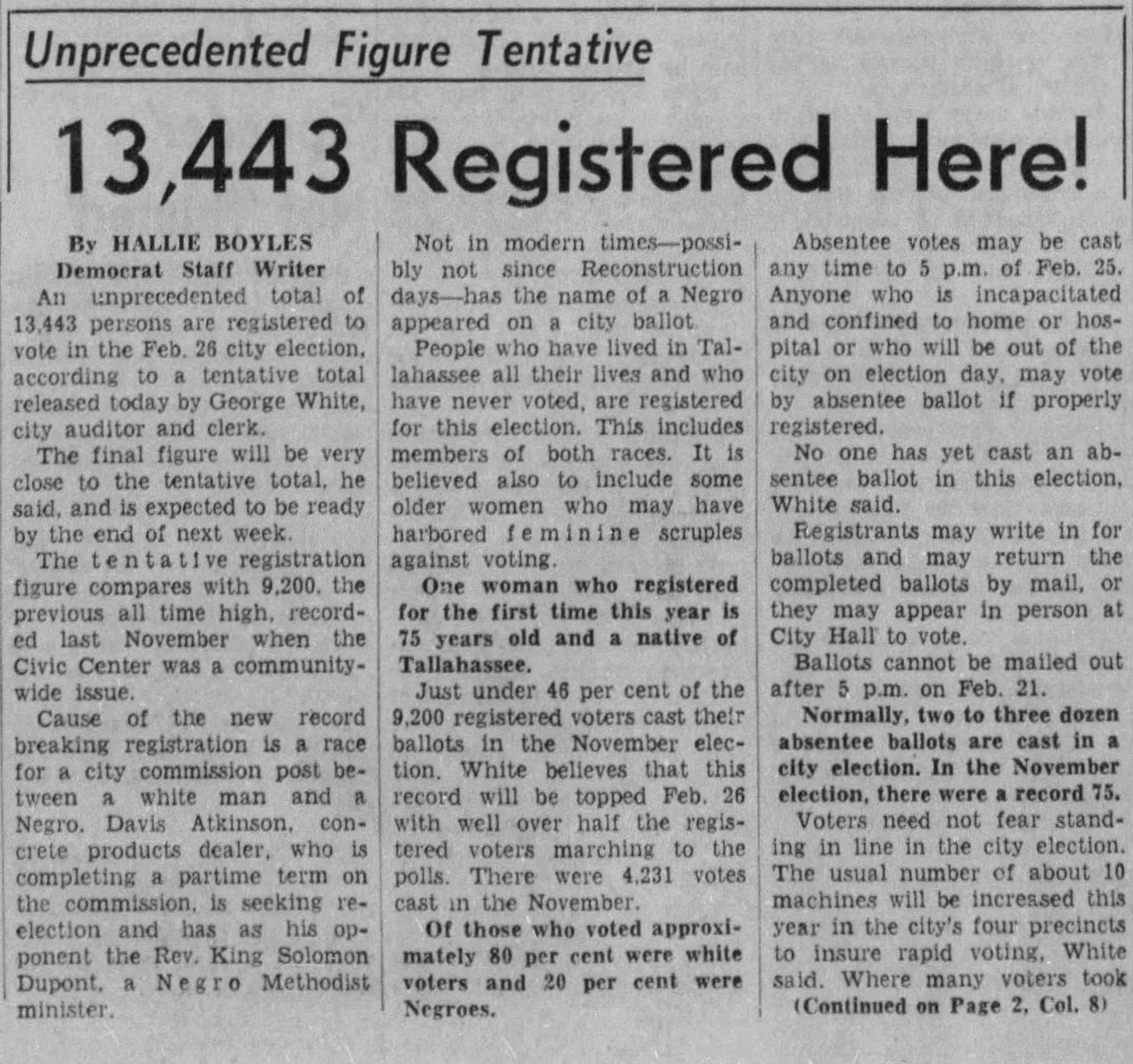

The tension of the boycott and the unprecedented nature of having a black candidate for commission led to a spike in voter registration in the city. At this time, the voter rolls were purged every 2 years (you had to affirm you wanted to stay on the roll by responding to a letter) and you had a to register separately for city races. City registration went from 9,000 to 13,000 in just a few months.

As the reports indicated, registration increases were due to black and white registration efforts. Unlike most of its neighbors, Leon County did see notable growth in black voter registration from the 1940s and to that point.

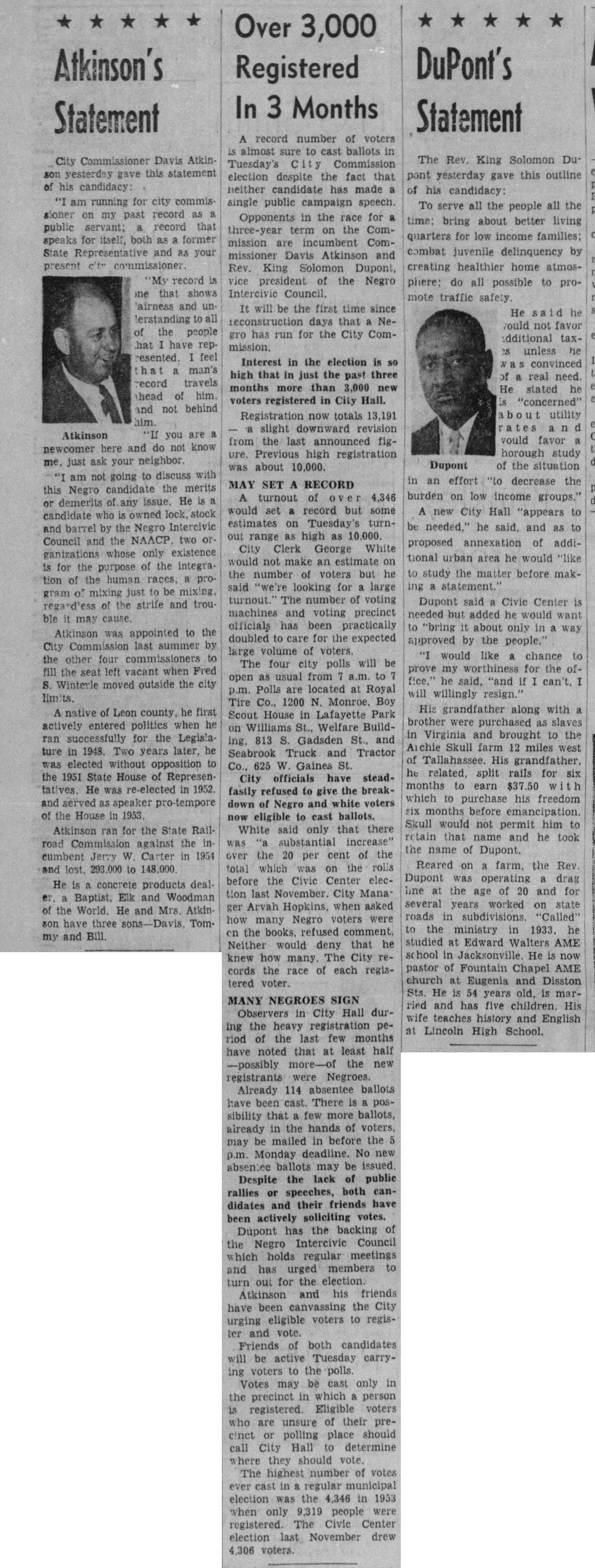

Below we can see statements from both candidates, as well as a further story on the voter registration drives. Notably the city appeared to be apprehensive about revealing the race totals for registration, but observers indicated almost half the new registrants were black. This shows there was a far bigger pool of un-registered black residents compared with whites. The city, meanwhile, was still over 65% white via the census, even more so when it came to the voter rolls.

David Atkinson, the appointed incumbent who used to serve on the state house, was an open segregationist. He refused to debate Dupont, who he referred to as “this negro candidate” - and accused him of being a pawn of bigger forces.

I am not going to discuss with this Negro candidate the merits or demerits of any issue. He is a candidate who is owned lock, stock, and barrel by the Negro Intercivic Council and the NAACP, two organizations whose only existence is for the purpose of the integration of the human races, a program of mixing just to be mixing, regardless of the strife and trouble it may cause.

Time has not looked back at Atkinson with kind eyes. While the paper editors did not appear to talk in such terms, they did nothing to push back on such statements. Atkinson’s rant stands out for how bitter and nasty it is. He comes off much more as a George Wallace type with that statement.

The Results

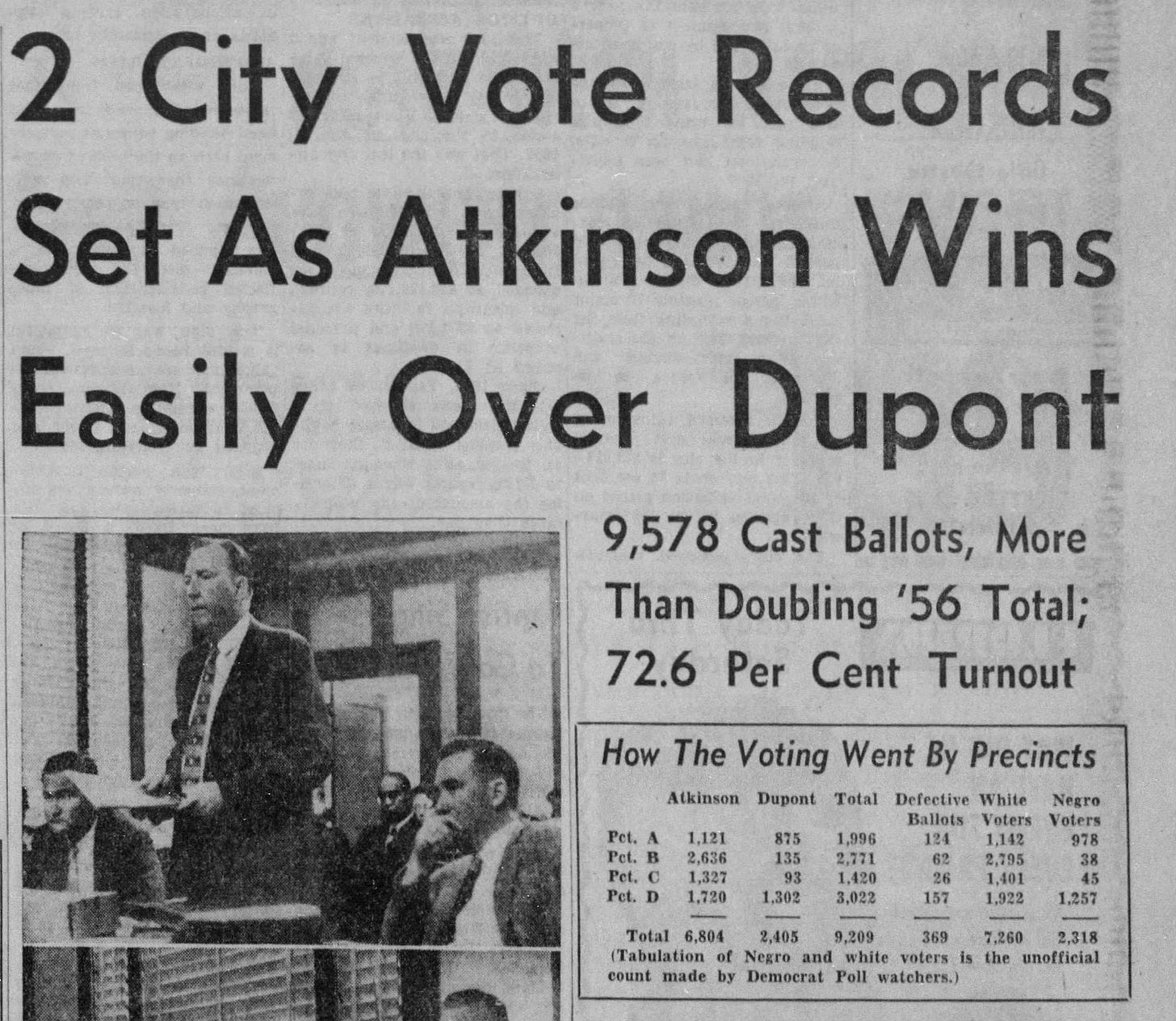

On February 27th, the city smashed all voter turnout records with 9,578 ballots cast. This blew past the record of 4,346 set in 1953. A stunning 73% turnout out to vote. Unfortunately, with registration still heavily white, it was an easy victory for Atkinson.

Atkinson was able to win thanks to clearly heavily racially polarized voting. His total was only slightly below the total whites votes cast. In addition, the precinct results show clear correlation with race and vote. Here is how the vote looked geographically.

At the time, the city used its own precincts, with the town divided by the intersection of Tennessee and Monroe streets, and voters casting ballots in whichever corner of the city they resided. The precincts east of Monroe street were heavily white and dominated by the older families of the town. Precincts A and D, west of Monroe street, were more racially diverse and home to the student populations. The power of student votes would increase with time, but tat this point FSU and FAMU (the historically black college) were still much smaller.

The above map shows the city’s borders for the time overlaid with the current street map. I do have the aerial imagery for the time, so here is that basemap below. It may be hard to see, but it shows how much emptier the region was compared to today.

The correlation between race and the vote was 0.99 - a near perfect correlation of race to vote. Dupont did well with nonwhites and the students who bothered to vote, but was a non-starter with the city’s white population.

While he did not win, and likely never expected to win, Dupont’s run was an important first step on the path to representation in the city.

Lasting Legacy and Continued Fight

Dupont didn’t win his race for commission and Atkinson would go on to server for many more years. However, Dupont’s run put the white establishment on notice. One year later, the newspaper had articles speculating if a black candidate would run for city council again. It would actually take until 1963 that a black candidate would again run for office. However, that election would kick off a series of races ultimately culminating in the city electing its 1st black commissioner in 1971. I will cover the path to that election and its aftermath next. However, the story does not end in 1971, and we will see an evolution in racial coalitions and changing city politics as we follow this saga.