Issue #158: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 2: A City in the Civil Rights Era

The 1960s in Tallahassee

Today I have Part 2 of my series on racial representation in Tallahassee. This is a series I am doing covering the efforts of black leaders to win elected office in Florida’s capital city. On Monday, I did my piece on the backstory in Tallahassee and the 1957 election. That year, Reverend Rev King Solomon Dupont became the first black candidate for City Council since Reconstruction

Part 1: The Civil Rights Reverend vs the Segregationist

The race saw Dupont take on segregationist Davis Atkinson. He would not win, with the vote very racially polarized, but he was an important first step in the march to progress. Today I will cover Tallahassee in the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s. This will look at Leon County in the context of national politics, but also further efforts by black candidates to get elected.

Lets begin.

The Campaign of Samuel Howell

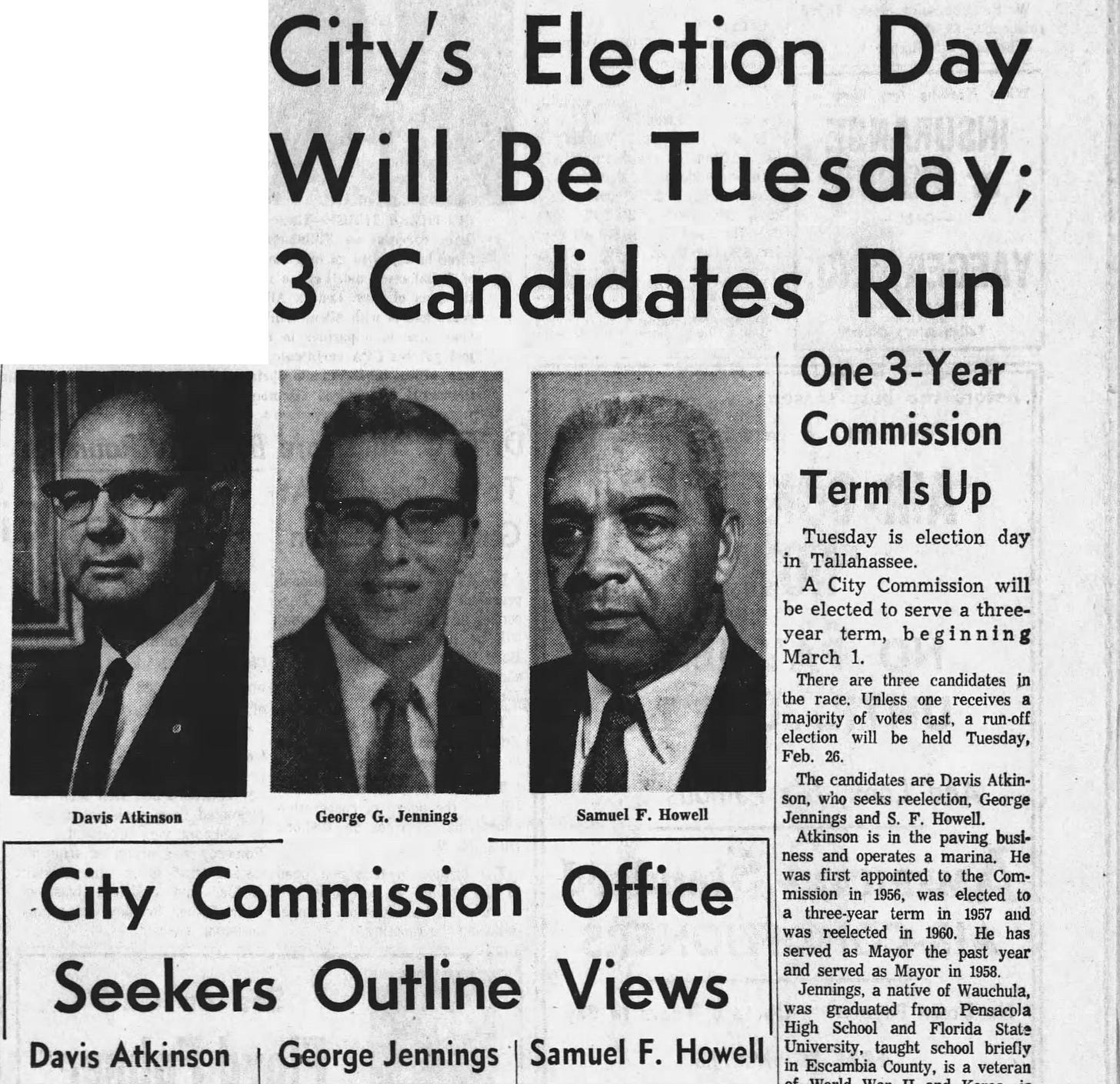

After the 1957 commission race, the next several elections would be much more quiet. Black leaders focused on voter registration efforts and increasing equality within the city. It would not be until 1963 that another black candidate ran for city commission. That year, insurance man Samuel Howell decided to challenged Davis Atkinson, just like Dupont had 6 years before.

The election did not see a great deal of public discussion about race like the 1957 contest did. Howell focused on his support for urban renewal with the aid of federal dollars, while the conservative Atkinson insisted on not taking mandates from DC. Atkinson would end up easily winning re-election. I don’t have precinct data, but these were the vote totals.

Davis Atkinson - 5,055 votes - 72.5%

Samuel Howell - 1,687 votes - 23.2%

George Jennings - 227 votes - 3.3%

The city continued to be a majority-white and conservative town. The registration books were up to 16,500, up about 3,000 from the 1957 contest. The major growth in the city was not there yet.

One year later, in February of 1964, Curtis Corbin, a retired merchant and veteran, was the lone black candidate in a field of four. However, in a race dominated by major personalities, namely between Incumbent Hugh Williams and attorney John Ausley, Corbin secured just 6.6% of the vote.

The early 1960s were much more contentious in Tallahassee around national Civil Rights issues.

National Politics in Leon County

Later in 1964, Leon County would break its streak of Democratic dominance, backing Barry Goldwater for President. Goldwater received 59% of the vote, largely winning the areas that did not hold large black or student populations.

The win by Goldwater showed the county and city (and the city was a vast majority of voters) were still racially conservative. Its not possible to garner the exact vote within the city boundary, as the precinct lines don’t match. Goldwater very likely won the city, but by a narrower margin. Precincts 1, 11, and 2 covered west Tallahassee, matching the pattern we saw in 1957 that showed the west end of the city was more racially diverse (and would grow more liberal as the FSU and FAMU Universities grew). The east side of the city remained whiter and more conservative.

The same time that Leon backed Goldwater, it voted heavily Democratic for all the other races. The vote here was absolutely about civil rights and LBJ’s progressive policies.

Four years later, Leon would back George Wallace for President in his 3rd Party bid. Wallace was running still as a segregationist, but he was toning down his message slowly at this time. Wallace’s campaign focused heavily on working class whites, who’d begun to rebel against federal government focus on integration. Wallace won the county by dominating outside of the city proper, especially in the white rural south end of the county.

The results in Leon really highlight the different coalitions. Nixon still won some of the upper-income suburbs emerging outside of the city while Humphrey’s backing from students and black voters allowed him to narrowly carry Tallahassee itself.

Civil rights was a major issue in Leon County at this point. The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act led to major showdown regarding the city’s public pools.

The Segregated Pools Controversy

In 1964, there were 3 public swimming pools owned and operated by the city of Tallahassee. Two of these pools were whites-only while the third was for black residents. The passage of the Civil Rights Act meant the city could no longer segregate the pools. In the beginning of July, just have the act was signed into law, 3 black kids went to one of the white pools to stage a “wade in.” Fearing lawsuits and unrest, the city closed the pools on July 4th. They claimed the budget for maintenance was not there, but no one on any side of the issue believed that. The city clearly expected lawsuits if they enforced segregation, but likely also feared racial strife and backlash from white residents if they integrated.

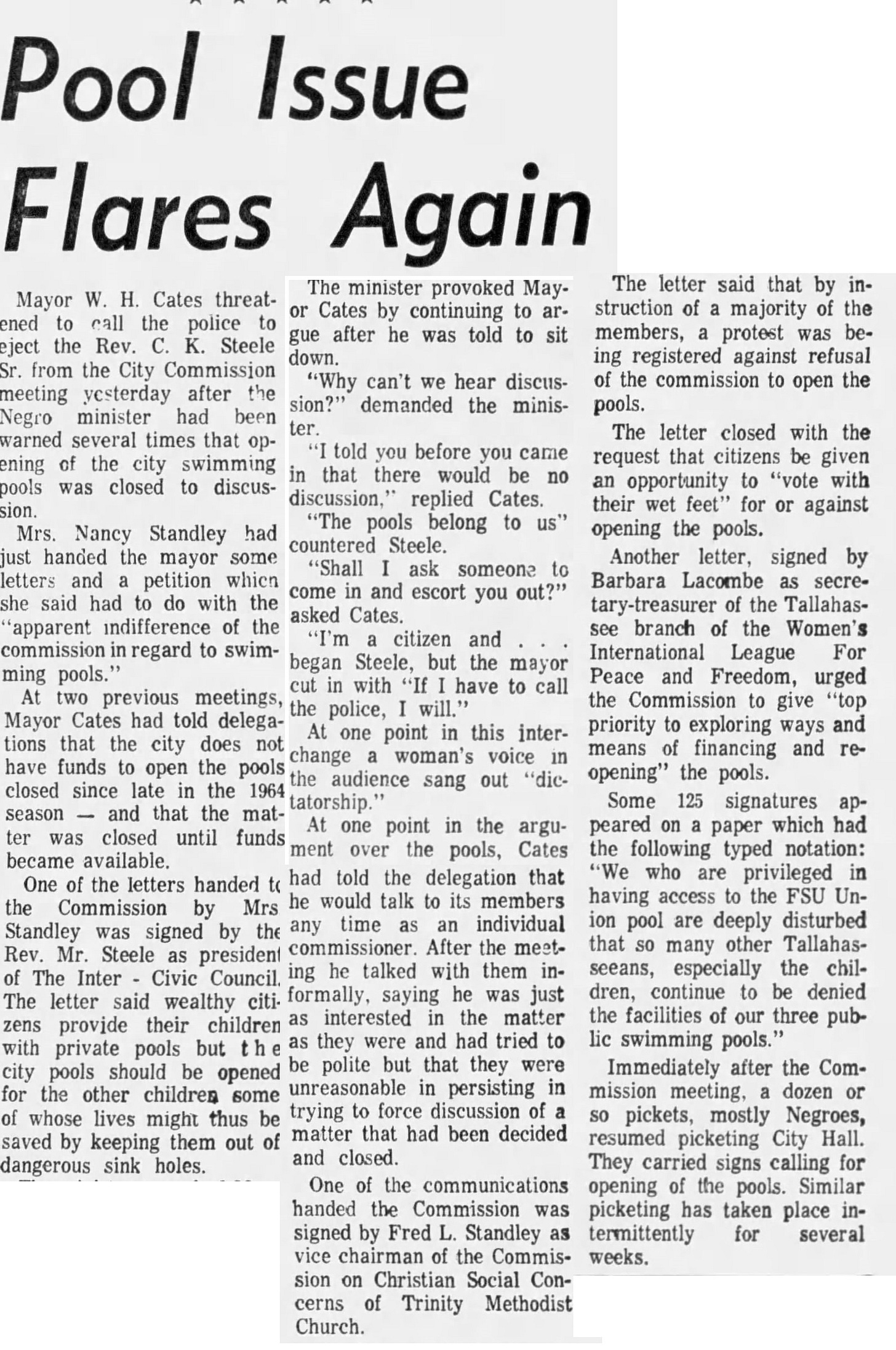

The pools would remain closed for over 3 years. Through that time, the issue would simmer and then boil over. Many groups wanted the pools back, especially in the black community. Reverend C.K. Steele, who you will remember from the 1956 bus boycott I discussed in my last article, was a major pusher for re-opening the pools. The NAACP even tried to sue to the city to re-open them. In one city commission meeting, Commissioner/ Mayor (the city commissioners rotated being mayor) W. H. Cates threatened to have Steele arrested for hounding commissioners on the issue.'

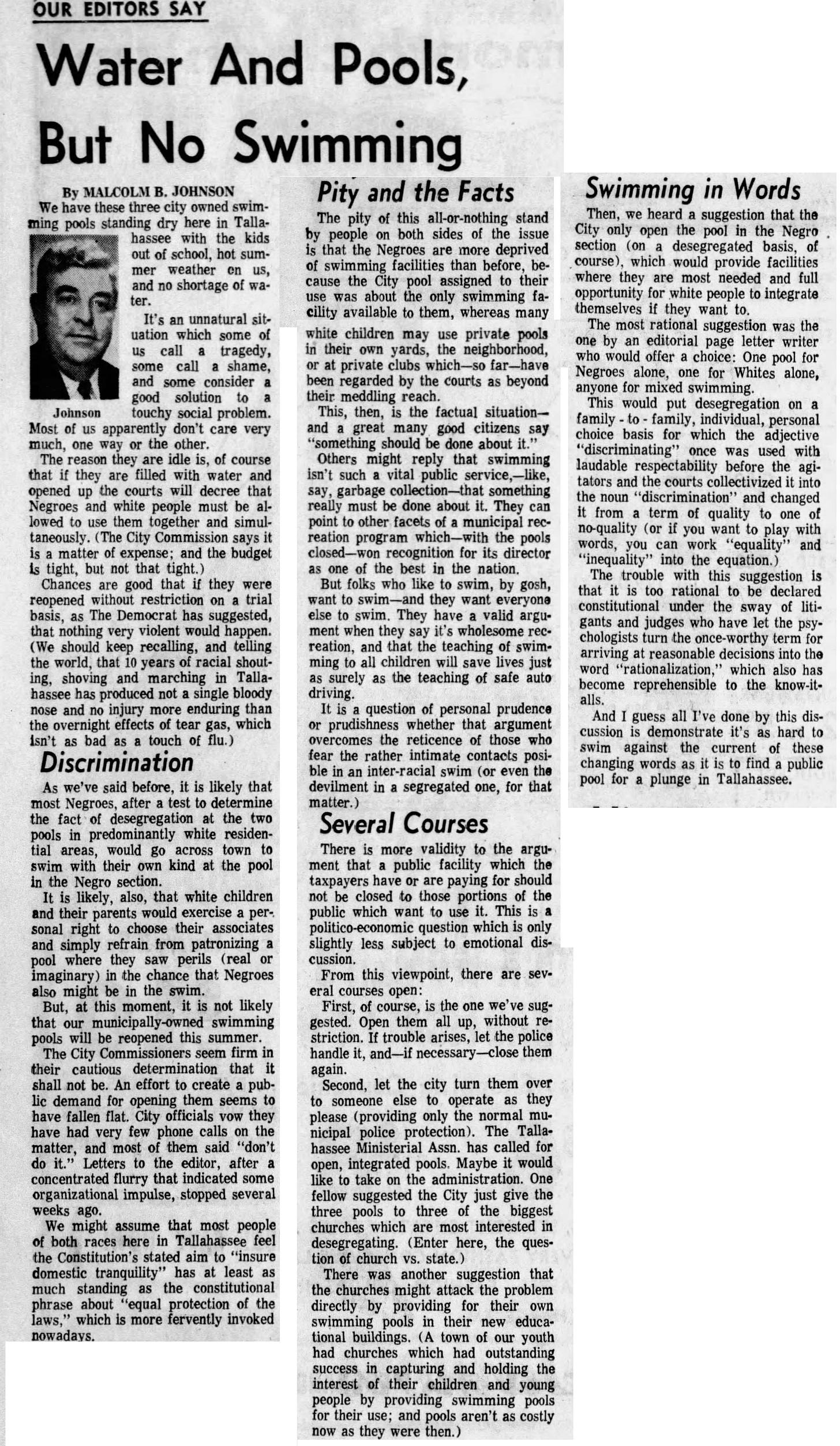

The newspapers largely sided on re-opening the pools. However, opinion pieces still displayed the paternalistic “lets be slow” approach. Editorials like this one questioned why there couldn’t be a black pool, white pool, and integrated pool; hence missing the point entirely.

Commissioners finally decided to deal with the issue in 1967. With a few new faces on the still-all-white dais, the city voted to put the issue before the voters. A straw ballot was approved for the summer that would ask voters if they wanted to re-open the pools with integration. Commissioners Spurgeon Camp, Gene Berkowtiz, and John Rudd vote to place the issue on the ballot. Commissioners W.H. Cates and George Taff voted no. Cates showed real hostility to the move, claiming the vote was out of order and warning the YES commissioners that the voters would punish them.

The election was entirely by mail, held in late July. On August 1st, the canvassing board announced the YES side won with 53% of the vote. Turnout was right around 50%, which beat many city council races. The vote below reflects the east-west divide of the city.

The pools would officially re-open the next summer, as many repairs were needed after years of no upkeep. The vote settled the pool issue, but reflected the divided city and its still evolving racial stances. I have no doubt the the city would have voted NO at the beginning of the decade.

This was the political situation heading into the city council elections of 1969.

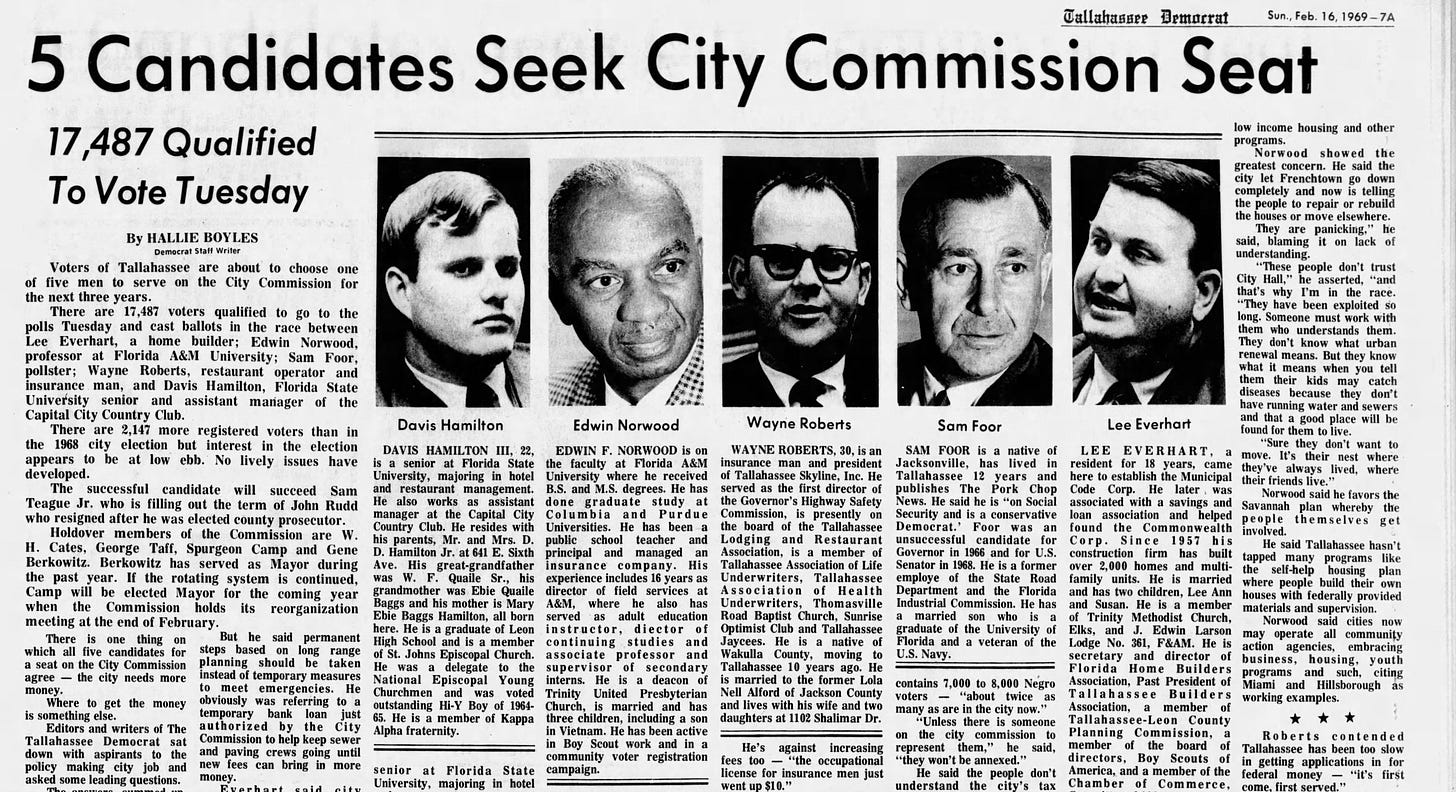

The Candidacy of Edwin Norwood

1969 was the next time a major black candidate ran for city council That year, Edwin Norwood filed for the crowded race for an open commission seat. Norwood was a well-accomplished man. He was a faculty member at FAMU, received a bachelors and masters from the school, and did post-graduate work at Columbia and Perdue. Norwood was the first black man to work for a Governor’s office in modern Florida; having served in Haydon Burns’ administration as a consultant for the Department of Economic Opportunity.

Norwood filed on February 1st, with the primary set for February 18th. This again reflects the short campaign season in Tallahassee back then. In his announcement, he said

“I thought it was time for Tallahassee to have somebody from the black community to represent this large group in housing, employment and other areas.”

In total, five candidates filed for the seat.

The race was considered fairly quiet, with candidates largely focused on economic issues around utility rates, taxes, and further development. Norwood did not shy away from race, however. In his statements, he highlighted that many communities south of Florida A&M had not been given the chance to vote to be annexed, with Norwood (correctly) speculating that the reason was it would double the black population of the city. This was at a time where the city began growing in land size, and annexation would often become a charged issue.

“Unless there is someone on the city commission to represent them, they won’t be annexed.”

The first round of voting was held on February 28th. A runoff was expected. Lee Everhart, a prominent developer and community leader came in clear first, taking 49% of the vote, just avoiding a runoff. Norwood made history, however, securing a spot in the runoff with 35%; a first for black candidates. The city divide was on display with the east-west split. Norwood did well in the University and racially diverse precincts, but Everhart was the candidate of the older white families. Everhart benefitted from stronger turnout in the heavily white areas, while turnout was lowest in Precinct D, home to a large black population.

In the runoff, Everhart and Norwood focused on economic issues. Norwood highlighted his lack of ties to the power structures of the city, pledging to offer a fresh voice on the council. Like in the primary, he did not shy away from race.

“I am a Negro, but I am not running merely as ‘the negro candidate.’ My election to the City Commission can mean representation for all the people of Tallahassee. I can add a new voice and a new understanding that will mean real growth and progress for our city.”

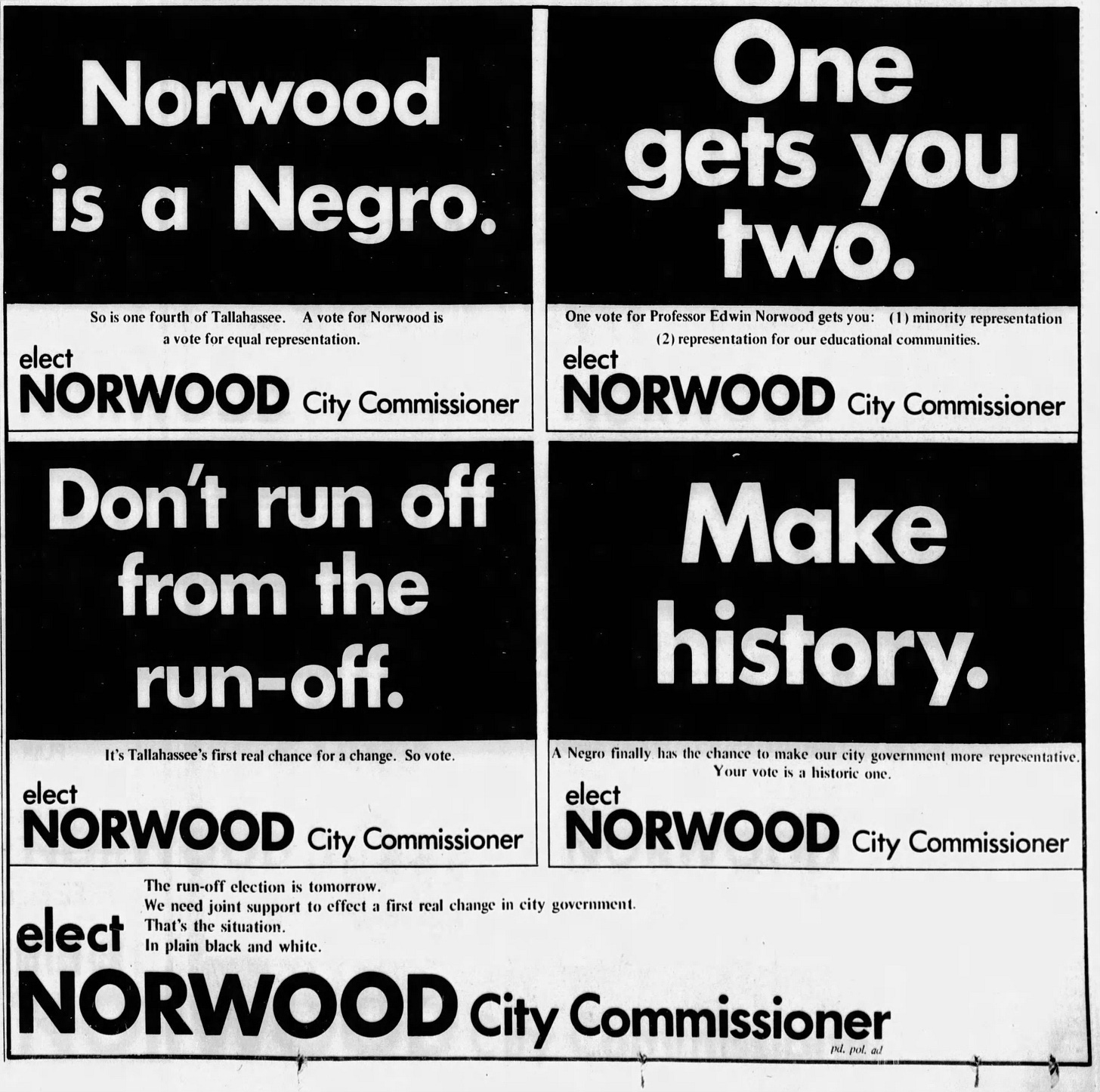

Ads in the newspaper supporting Norwood aimed to get black voters to the polls and give representation to the community.

The runoff, however, would not go Norwood’s way. Everhart secured 62% of the vote. Norwood’s 38% was the best performance for a black candidate at this time. Turnout did not help, as the gap in that repeated from the primary. However, Everhart still would have won if turnout was up in Precinct D.

Norwood did not blame race on his defeat, however.

“There was no issue of race…..it was just town against gown”

If you have never heard that reference, it broadly means the separation of a larger city with this college/academic community. Indeed Norwood was strong in the “gown” section of the city.

Annexation Politics

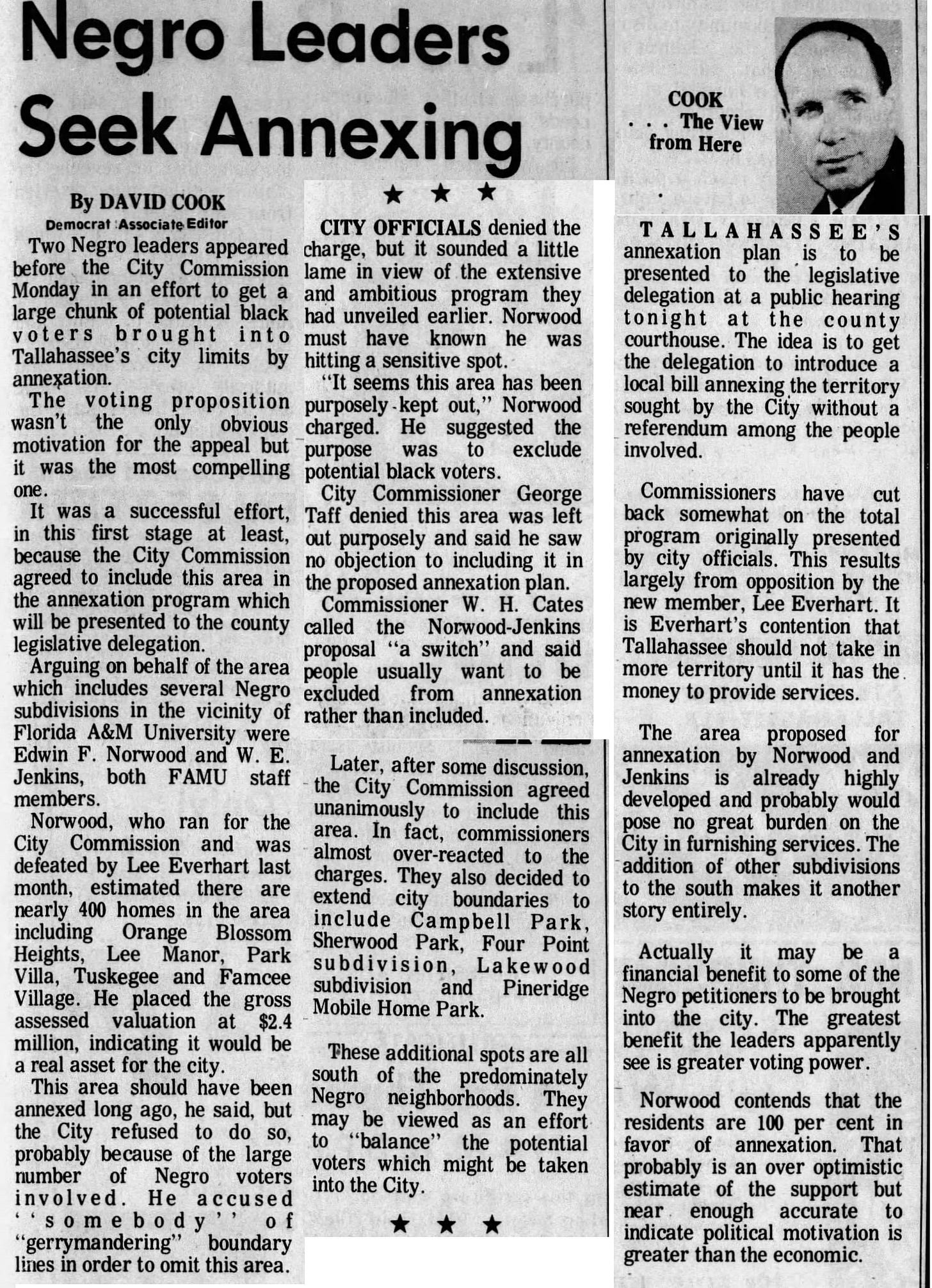

After Norwood’s loss, annexation issues would flare up again. Proposals to have the heavily black areas south of Florida A&M did pick up steam, with black leaders heavily pressuring city leaders on the issue.

Back and forth debates would continue over the next few months. Later that year, the city commissioners would vote 4-1 for the legislative delegation to push through a bill that would annex several parcels of land. Everhart was the lone no vote, sighting cost issues, but its hard to not assume he was shaped by the race against Norwood.

The final set of annexation is in blue below. It included the heavily black areas in the south, but also picked up some other communities as well.

That annexation would then be followed by some additional tracts in 1971. This put the city at 82,000 people by the end of 1969. For context, in 1957 the population was around 35,000. The city growth was part annexation but also massive population growth as the city and university systems expanded. These annexations largely happened because the areas were already developed. Over a decade ago, many of these regions were largely empty land.

The city would continue to grow through the next several decades, and get more progressive with time. Before then though, Part 3 will cover the 1970s and the first black commissioner elected!