Issue #114: What the Alabama Redistricting Case means for North Florida

Allen v Milligan gives VRA a Boost

Yesterday offered up some big redistricting news from the US Supreme Court. In a major shock to many court watchers, SCOTUS ruled 5-4 that Alabama would be forced to redraw its congressional districts and add a 2nd black-majority district.

You can read the full ruling here: Allen v Milligan

Many redistricting experts worried that the ruling would be a decision striking down Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Instead, the court not only preserved the VRA, at least for now, but also issued a ruling that expands minority representation.

Lets look at this case and what it might mean for other states - including Florida - as well.

Alabama Court Decision

The Alabama case revolves around a dispute over the state’s 7 congressional districts. After the state avoided losing a seat via the census, a growing movement built to push Alabama to draw a 2nd black-majority seat. Since the 1990s, the state only had one black-majority seat with the remaining being heavily white. This led to a very politically and racially polarized plan, as best seen in the breakdown of the 2017 US Senate Special election in Alabama.

Republican lawmakers, predictably, refused to draw a 2nd black-majority seat. The final plan they passed, per 538, can be seen below.

The argument from those who eventually sued the state argued that Alabama’s 27% black voting age population warranted a 2nd district. A lower court agreed and implemented a map in 2022, but SCOTUS stayed that decision until they could hear the full case. The 2022 elections went ahead with the 6-1 map. In yesterday’s SCOTUS opinion, Roberts and Kavanaugh sided with the three liberals in favor of Alabama’s black voters, meaning the 2014 plan will be a 5-2 plan.

An example of what a plan could like, again curtesy of 538, can be seen below. This was drafted by one of the experts for the plaintiffs who sued the state.

The state will be forced to draw a new plan for next cycle, and we will see how the final lines are configured. To throw some cold water on one item being discussed on twitter, no the state is not going to try and draw a 50% black seat that due to bad turnout is actually GOP-leaning. These court cases are not just about hitting a census %, they are about “the ability of a minority community to elect a candidate of their choice.” Issues where turnout and census don’t match have led to courts ordering redraws. This happened with Mississippi’s State Senate plan a few years back.

This case will likely have impacts on similar lawsuits - namely a case in Lousiana. However, it does have the potential for broader applications.

And the question everyone asking me is, what does this mean for Florida?

North Florida Redistricting Lawsuits

I’ve been covering the saga of redistricting in Florida, especially North Florida, for some time now. There are current two lawsuits ongoing about redistricting here, but first let me set up some reminders of how we got to where we are.

Quick History

I’ve delved deep in Florida’s redistricting history, from statehood to the present day. My Florida Redistricting History Series is over 30,000 word and has everything you could need to understand the logic behind old maps. I also looked extensively at the debate around North Florida and providing representation for its black voters in this separate piece. But lets give a short history here.

In 1992, Democrats, who still ran the Florida legislature, failed to agree on a Congressional plan. The court implemented a proposal that created 3 black-performing seats. One was the 3rd, which looked like… well looked like this.

This district was just narrowly 50% black voting-age population.

This seat was won by Corrine Brown, a Jacksonville State Representative. However, in 1996, the court struck down this plan, arguing that it improprerly used race. The district clearly only used race, and no other redistricting pricniples, to aquire its shape. A new map passed by the legislature was upheld by the courts and remaining a black-performing seat.

That district was just 42% BVAP, but still performed electorally for black voters thanks to being deep-blue and majority-black in the democratic primary.

This district would see changes in 2002 and 2012, but largely retain a similar shape - in essence being a Jacksonville to Orlando seat. Republicans and Corrine Brown defended the seat even as opposition to it grew.

In 2010, voters then passed the Fair Districts Amendments. These two proposals (Amendment 5 was for State Legislative Seats, 6 for Congressional seats) put new redistricting standards into effect. Both got just under 63%.

The redistricting rules for redistricting banned political gerrymandering but also set up compactness and race rules. While compactness is important, racial concerns due to take precedent under the proposals. The two tiers are laid out as follows.

Tier 1 – Lines cannot be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or party. Districts also cannot be drawn to diminish the ability of racial or language minorities to elect candidates of their choosing. Districts must be made up of contiguous territory.

Tier 2 – Districts must be compact, as equal in population as possible, and honor administrative boundaries when possible.

The measures bar maps from retrogression, aka reducing the influence of minority voters in remaps. This means, baring demographic changes that make the status quo impossible, black or Hispanic performing districts are protected.

These measures were used in 2015 when the Supreme Court of Florida struck down the Congressional plan. A new plan was implemented, which redrew North Florida to have an east-west black-access seat.

The plan allowed a new black-access seat to be formed in Orlando, while also linking the historic black communities that data back to North Florida’s plantation era.

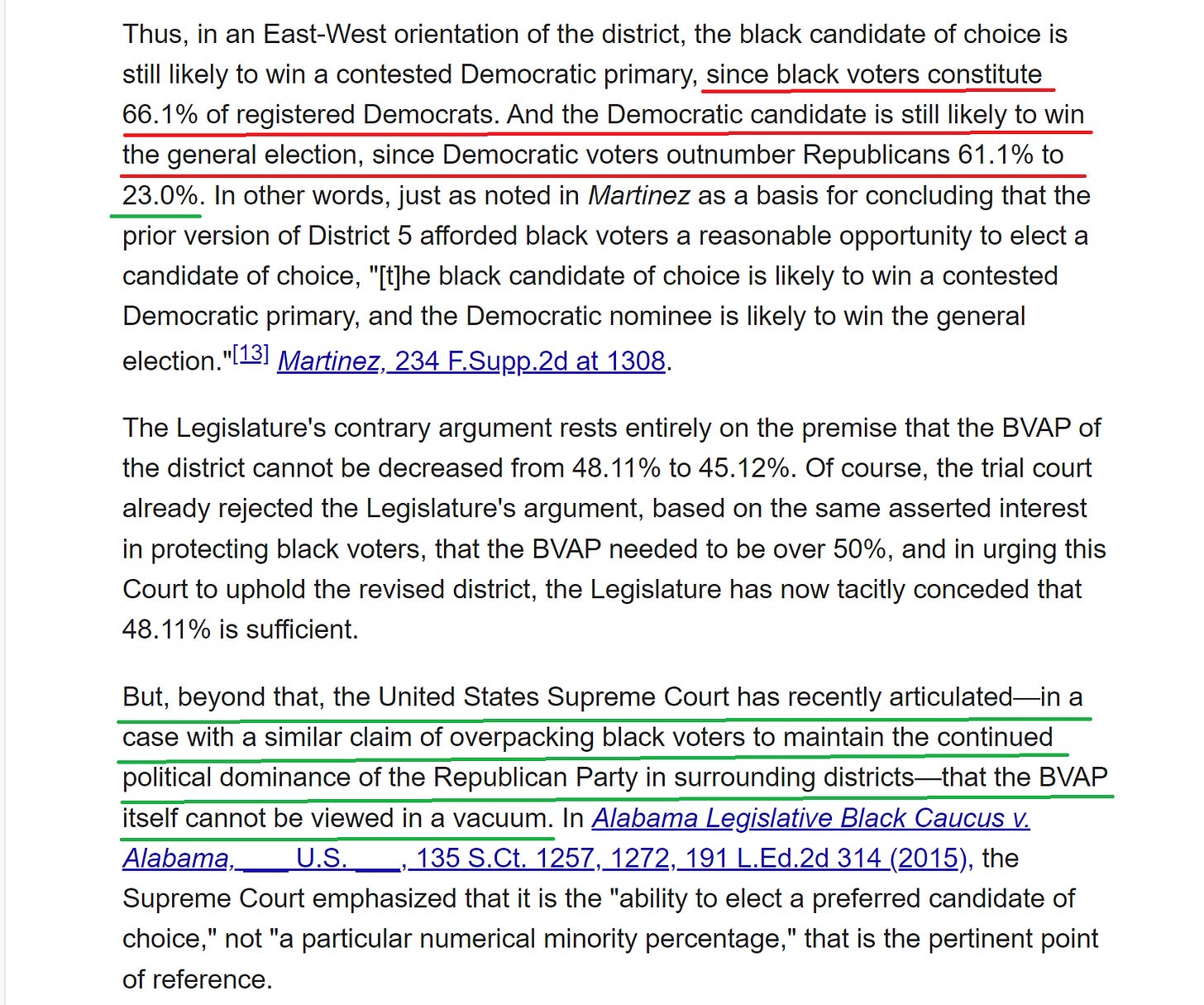

Under the 2015 plan, the 5th and 10th districts became functionally black-performing districts. What does that mean? Well Florida, like many states, due not just look at race via the census. Lawmakers of both parties, as well as the Florida courts, have used what is known as “Functional Analyses” to judge districts. I delve into this more in my 2012 redistricting article. In short, the political performance of seats can be used to determine if they meet the standards to be considering a minority-access seat. In a case like the 5th or 10th, these seats were both heavily Democratic and were majority-black in their democratic primaries - making them functionally black. You can see an example of this from the Florida Supreme Courts 2015 Redistricting Lawsuit.

The court specifically sited that the census data was not all that mattered here - political data could be considered for these purposes.

Over the next several years, Demographic change, namely Hispanic growth, in Orlando, would make the story of the 10th district much more complicated. However, the 5th district remained firmly black-access, with a Democratic primary well over 60% black across all elections. Al Lawson, a longtime lawmaker from Tallahassee, would defeat Brown in the 2016 Democratic primary and held the seat through 2022.

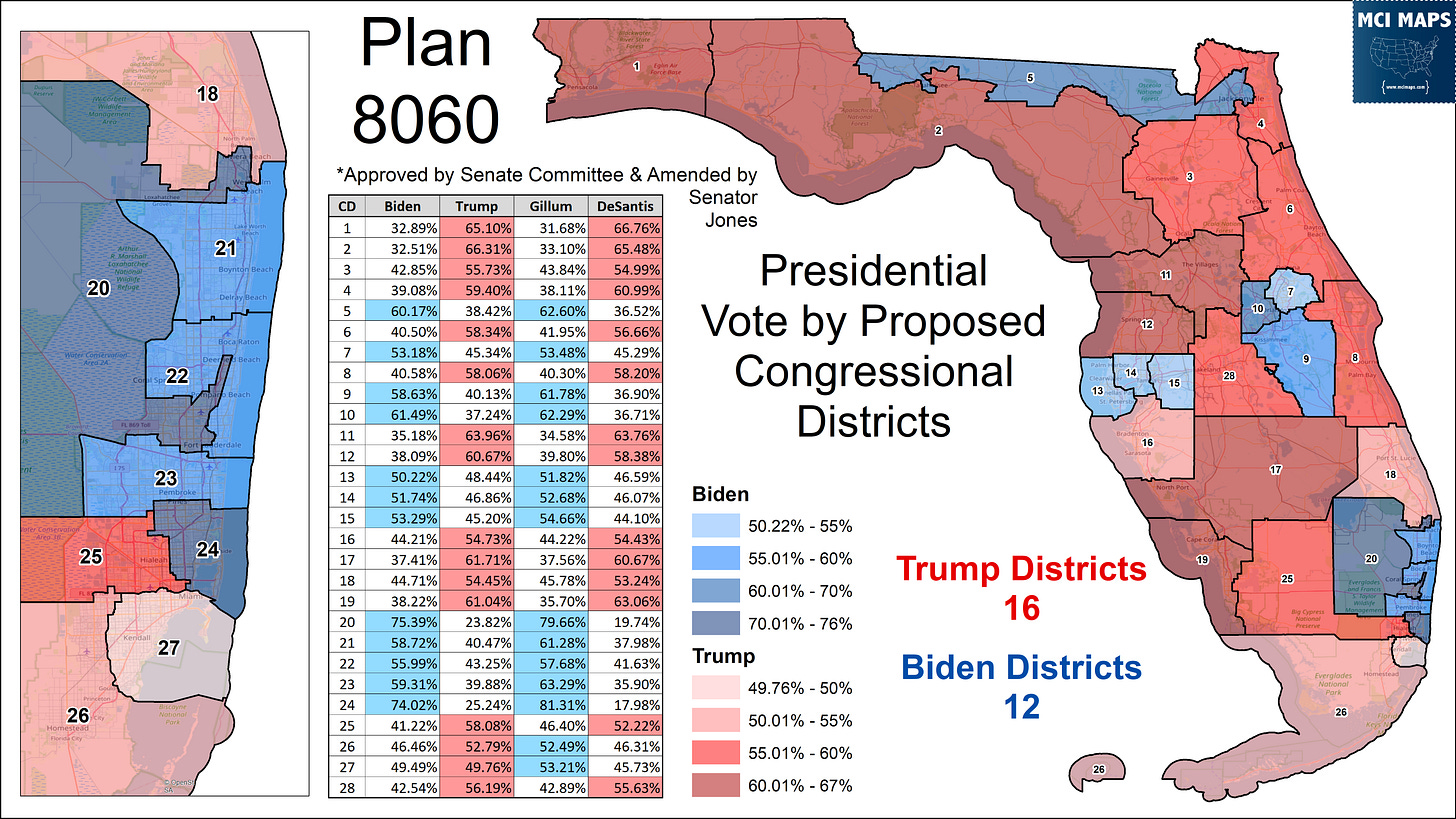

When redistricting began in Florida in 2021, both chambers of the legislature proposed maps that kept the status quo in North Florida - with a Tallahassee to Jacksonville district. The State Senate would pass this plan, see below.

Governor DeSantis, however, submitted his own plans, which aimed to destroy the 5th district. The first plan was proposed in January and further iterations came. Lawmakers tried to propose a compromise that saw a black-access seat drawn in just Jacksonville.

A Duval-only district would be around 60% black in a democratic primary and would be moderately Democratic, possibly fulfilling Fair Districts requirements.

This plan was vetoed by the Governor, and his final proposal would end up getting the rubber-stamp from the legislature in a chaotic special session.

And now, quiet predictably, lawsuits are ongoing.

There are MANY articles in this substack series looking at how that 2021-2022 process carried out. But for ease of access - here are key article I recommend for more detailed at-the-time reactions

Honestly if you just go back the start of this newsletter and move forward, you will catch even more real-time coverage of the entire saga.

So lets get back to the courtroom

Where Things Stand

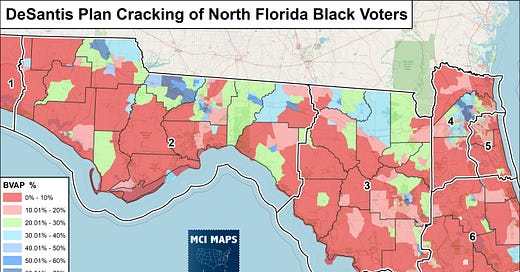

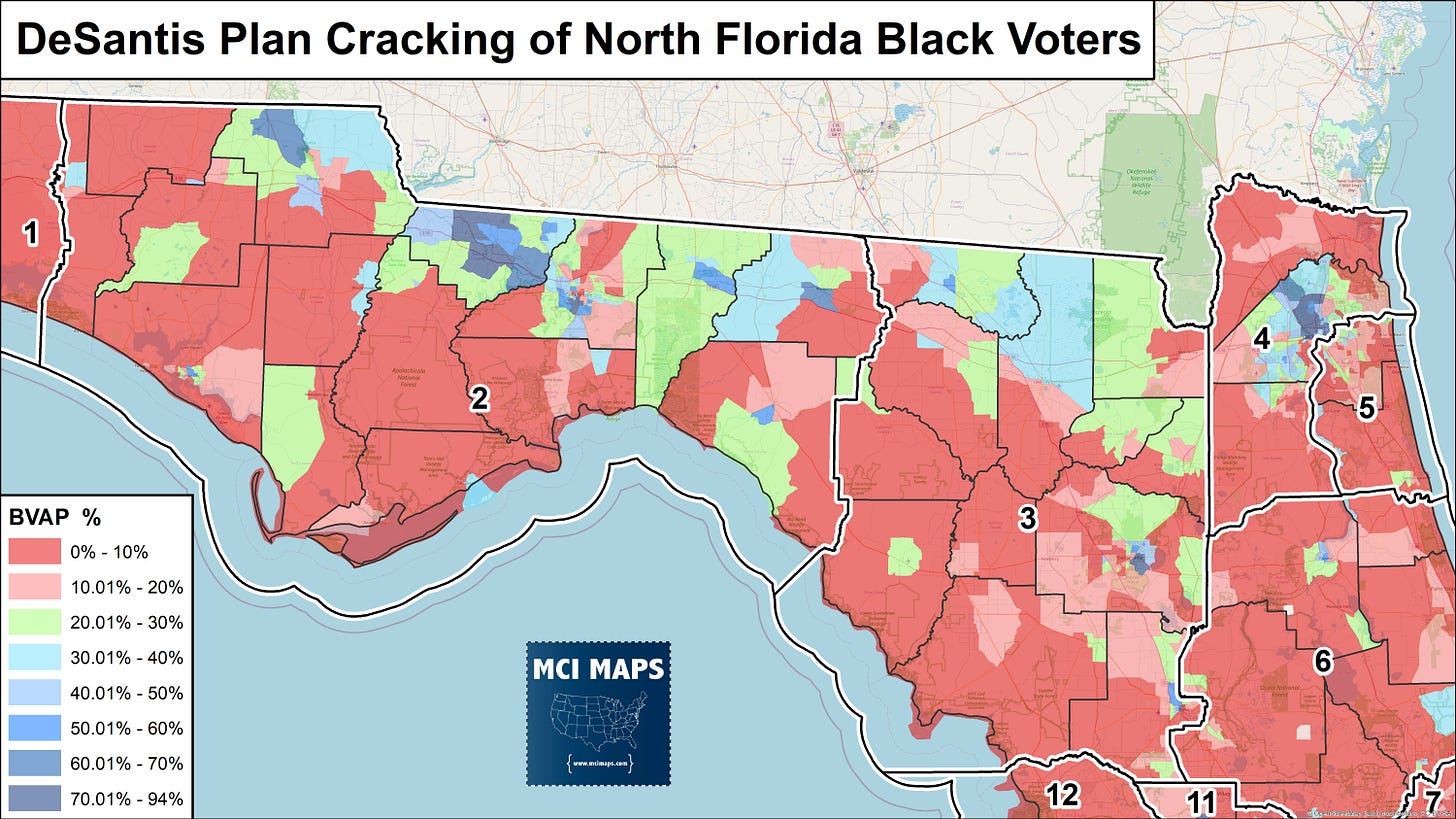

There are currently two lawsuits ongoing in Florida. One is a federal case, Common Cause v Byrd, which revolves around 14th amendment claims that the final map intentionally discriminated against black voters. Looking at how “cleanly” and conveniently the DeSantis plan cracks the North Florida black population, I think there is a good case for this claim.

The second suit is Black Voters Matter vs Byrd, which is behind tried in the state courts. This case argues that the elimination of the 5th district constituted retrogression in the Fair Districts criteria.

The state court is where I believe better chances lie, as there is prominent Florida law to go on here. The elimination of the 5th as a black-access seat is clear retrogression under Fair Districts.

Back in May of 2022, the court involved in this very case approved an injunction to reinstall a North Florida black seat. That injunction was stayed by the higher courts pending a full trial, so the 2022 elections went ahead under the DeSantis plan. Now both sides of this case are gearing up for a trial that will begin later this summer.

So what does the Alabama case mean for Florida? Well, lets be clear about a few things.

The Florida case hinges much more on Fair Districts than the VRA. I would not expect SCOTUS to order a drawing of an east-west 5th. They might not view it as compact, and the 5th wouldn’t be majority black. So I am not expecting proactive help from the federal court.

However, one item the DeSantis side was counting on was a court striking down Fair Districts all-together. The recent court filings show that the DeSantis side wants to argue that the Fair Districts, with its anti-retrogression standards, is unconstitutional.

Now the Alabama case does not mean “ok whew, Fair Districts is safe” - but anyone who claims its not a nudge in that direction is kidding themselves. A decision like the one for Alabama tells me this court is not interested in striking down the criteria states set up for themselves; at least not at the moment.

If SCOTUS isn’t going to invalidate Fair Districts, then the DeSantis side is counting a more conservative Florida Supreme Court to just ignore the law’s clear text. Now could that happen? Sure. It is a very conservative court, which I recently delved into more here. That said, this SCOTUS is also very conservative.

What is undoubtedly good for the plaintiffs in these lawsuits though, is that lower courts look at this type of precedent as they work their cases. The Supreme Court just gave a major ruling affirming minority voter rights in redistricting. This boosts the credibility of those arguing for stronger minority representation as these cases work through lower courts.

Does Alabama guarantee a return for a North Florida black-access seat? No. There is still a long process to go here. Does it help the cause, even if just a bit? Undoubtedly yes.