Issue #186: Black Representation in Tallahassee Part 7: Tensions and the end of "Old Tallahassee"

Tensions, tensions, tensions

Today is Part 7 of my series on Black political power in Tallahassee, Florida. In Issue 6, I discussed the campaign of Rosa Houston in 1974, the first Black female candidate in modern Tallahassee. In that issue, I discussed Houston’s bid and her call for more aggressive aid to Black and poor residents; and how tough it was for such a candidate to get the respect she deserved. I followed Issue 6 up with a Supplemental on James Ford, the city’s lone Black commissioner to that point. There I looked at how Ford advocated for Black issues at times while also remaining part of the inner-circle of Tallahassee; keeping white voters on his side.

You can see all issues so far written here!

After Houston’s 1974 loss, it was clear the city still had ways to go in its progression from a more conservative southern town into the racially liberal city it is today. By the mid 1970s, Tallahassee was not conservative, but more moderate. I discussed this more in my James Ford piece, but the city was moving in a more progressive election slowly. When it was sued in late 1974 by the Department of Justice for employment discrimination against black workers (namely never elevating black works to higher roles) - the city worked toward settlements and did not viciously fight the the issue. When the city brought on a new city manager in 1974, it selected Daniel Kleman, a young progressive from Dayton, Ohio that championed diversity and Affirmative Action.

The city had plenty of blind spots for race relations, but it was not as hostile as many other southern or “North Florida” towns were. That said, the 1975 elections that I will discuss today ere very tense. However, that tension was not often revolving around anything regarding race, but rather fights over coalitions, money, and “new” vs “old” faces. In a short time, many members of the commission would turn over. This didn’t relate to race as much, but it will be the subject of today’s issue, as it sets the stage for a litany of other contests to come.

Lets see why everyone was angry in 1975.

Coalition Politics and Scandal in 1973

By the time of the 1975 elections, the city was dealing with a great deal of tension. As I discussed in my James Ford supplemental, the city was being sued by the DOJ over discrimination around the lack of hiring of black people to leadership roles. By the spring of 1975, the city and DOJ were in the process of working out a settlement. However, this was hardly the only major issue for the time.

Back in 1973, the commission got hit by a scandal revolving around internal political factions. During that year’s elections, which I covered in Issue 5, Russell Bevis defeated incumbent Gene Berkowtiz while an open seat saw Earl Yancy defeating Larry Brock. Shortly after these elections, rumors swirled that Commissioner Loring Lovell has been behind the ousting of Berkowtiz and was backing Brock’s failed bid. City employees reported getting handouts from Brock supports recommending their votes to obtain a “solid friendly majority on the commission.” The implication was that Lovell, Brock, and Bevis would be that majority. Now, in modern politics this is a nothing story, largely internal intrigue. In small-town Tallahassee in 1973 this was the exact time of unseemly thing voters hated. Lovell’s efforts were exposed and since Brock had lost, he did not have his majority.

Shortly after the 1973 elections, Lovell was supposed to become the City Mayor; which at the time was rotated between commissioners. However, Lovell’s moves angered commissioners so much that he lost the vote, with only himself and Bevis voting for him. Commissioners instead went with Joan Heggens; who’d become the city’s first female commissioner in 1972. Two weeks later, still in March of 1973, Lovell announced he’d taken a job with the Florida Department of State and was hence resigning.

While he insisted it was not about the scandals above, its hard to envision he leaves in a different scenario. Commissioners tapped former member Spurgeon Camp to fill the one remaining year of the seat’s term. In the meantime, though, Bevis was hit by the taint of the Lovell scandal.

If anyone was hoping that would be the end of drama, they were sorely mistaken.

Drama, Resignations, and Recall in 1974

The year of 1974 was filled with far more tension and drama compared to 1973. It began with the announcement by longtime city manager Arvah Hopkins that he was stepping down by the end of that year. This came amid wide speculation that Hopkins was being pressured to step aside; largely due to it being viewed that his style was better served for a small town, not the growth the city was experiencing. I discussed this more in my James Ford supplemental, but the city’s selection of Dayton’s Daniel Kleman as the new manager marked a major change for the city, as Kleman represented a more progressive and aggressive outlook on city government and services.

The growth within the city, along with annexation debates, led to plenty of tension between city government and the developers and broadly the Chamber of Commerce. All this came at a time of a nationwide economic recession, leading to serious budget crunches. These budget concerns were real, so much so that during Christmas of that year, the commission would do its usual Christmas lights display downtown, but would have it timed to ensure citizens got to enjoy it while not spending a cent more than needed. It was belt-tightening time in many cities across the country. This was felt even more in Tallahassee since the city has so much land that cannot be taxed. At this time, the new Florida Capital Complex was under work for the city, and commissioners became concerned about how much untaxable land was being gobbled up. All the university and government building land in Florida is non-taxable, and Tallahassee has lots of both.

One issue that riled up developers was the city proposing to end the rebate it gave on utilities to developers and homebuilders. This brewing tension got so bad that developer Richard Pelham launched a recall drive against commissioners Joan Heggen and Russell Bevis. This move, which took place around May and into June of 1975, eventually died off, but created a great deal of tension at the time and left bad feelings all around.

The tension of the recall and non-stop budget-related issues lead to major changes within the city government. In August of that year, Commissioner Bevis, then serving as Mayor, resigned suddenly.

Bevis had been one of the candidates backing by Lovell back in the 1973 scandal and he was major backer of ousting Hopkins as the city manager. He was, like Lovell, a more forward-thinking and aggressive politician, but also was known to be abrasive at times. In stepping down, he cited the non-stop tension on the commission, the nasty attacks, and the drain the job had taken on his business and his family.

The resignation revealed even more fissures on the commission. One name floated for the appointment to replace Bevis was outgoing city manager Arvah Hopkins, who was about to formally step down and make way for Kleman. While commissioners Ford and Yancey were good with such an idea, Commissioners Jones and Heggen were FIRMLY against it. Commissioners ultimately went with businessman Don Price, who owned a few radio stations and other properties, for the post.

Then, as the year 1974 came to an end, another bombshell hit when Commissioner Heggen announced she would not run for re-election in 1975. Heggen, who broke ground as the city’s first female commissioner and mayor, said she was proud of the “sweeping changes” they’d undertaken in recent years, but the tension was so great that it was time for her to step aside. She cited the recall as a nasty affair though insisted it was not the main driver of her decision. Broadly she felt the reforms and changes were critical for the city moving forward while also hoping animosity would decrease with new faces on the commission.

The last few years had been very tense for the city of Tallahassee, and that was the environment the 1975 elections were held under.

Rosa Houston’s Last City Campaign

In 1975, two city council seats were up. In the group one race, appointed Incumbent Don Price opted to run in the election. This was technically a special election for the remainder of Bevis’ term; just one more year. It was in this race that Rosa Houston decided to make one more bid. Houston had run in 1973 (Issue 5) and 1974 (Issue 6) and generate a strong base in the Black community; but scared off white voters with her pushing for more progressive aid to the poor and Black communities. He big loss in the 1974 runoff meant a win in 1975 was very unlikely, but she would advocate her issues. She would be by far the most well-known challenger to Commissioner Price.

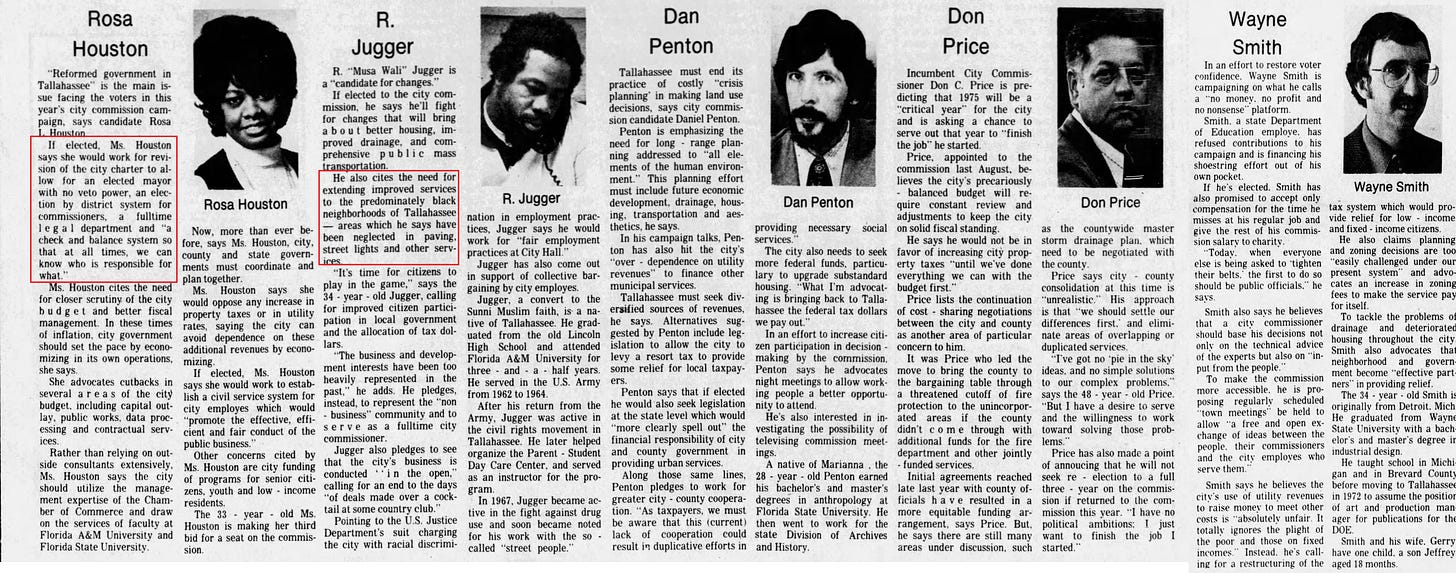

The full list of candidates for that race were

Don Price - Appointed incumbent and businessman

Rosa Houston - Young Black community activist and previous two-time candidate

Daniel Penton - A coastal zoning planner with the State of Florida

Musa Wali Jugger - Black Civil Rights and anti-drug activist. As best I know, the first Muslim candidate for office. Ran back in 1972 (see issues 4 and 5).

Wayne Smith - FL Department of Education Employee

A full look at the candidates is below, you can click the image for zoom ins.

Price made it clear that he was only running for the one year remaining on Bevis’ term and would not run for re-election in 1976. This race broadly had less drama than the other city council race, which I will discuss in a separate section.

As the campaign went on, the tensions and divisiveness of the last few years were a major issue; however, race issues rarely came up. Houston hit Price for comments he’d made the year before regarding fire services. Long story short, the city provided those services with the un-incorporated counting paying for coverage as well. When negotiations over raising fees became tense, Price threatened to cut off the services. All this tension and sniping stemmed from the budget concerns dominating the economics of the time. Houston also differed from Price in that she favored the city continuing to pay the Tallahassee Chamber of Commerce the $52,000 a year the city had been for their lobbying and research work. At the time the city, feuding with the chamber but also seeking to save money, had been pushing for a smaller fee. All issues largely stemmed around money.

As the races went on, the city was trying to form a settlement with the Justice Department over its employment discrimination suit (read the Ford supplemental for more details). However, the suit was not the major focus of these campaigns; rather it was budget and funding. Both Houston and Jugger advocated for moving city elections to single-member districts, which would aid minority elections, but this was not a issue heavily debated.

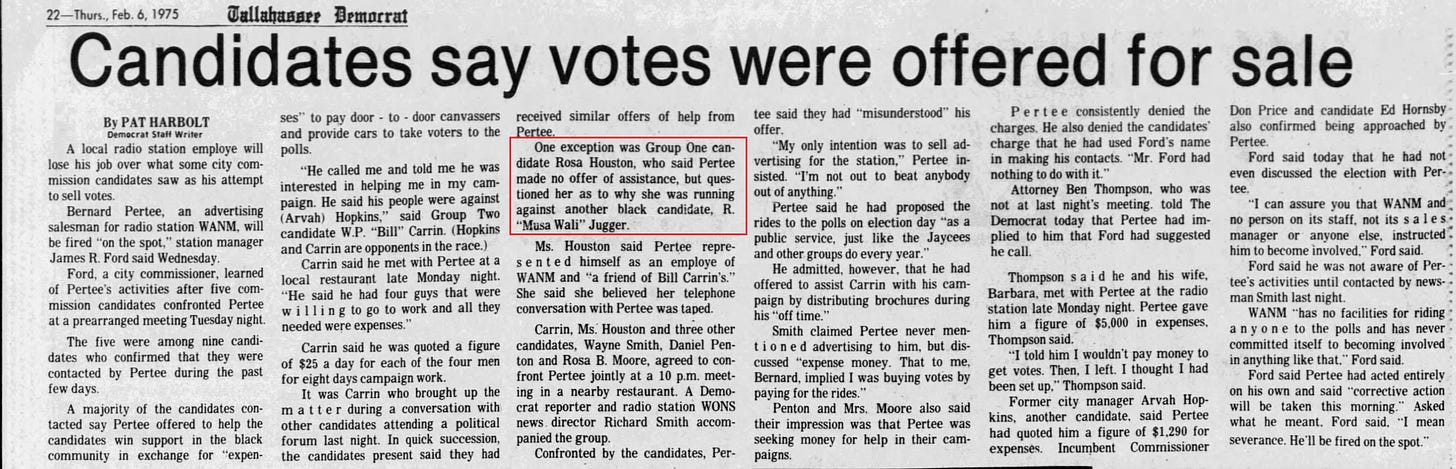

One race-based scandal that did emerge during the campaign revolved around a radio station. WANM, a Black radio station that Commissioner James Ford started just the year before, fired sales employee Bernard Pertee when it he tried to solicit money from candidates for campaign services; not just buying radio spots. It appeared Pertee had preferred candidates but also clearly shopped around trying to get cash. Notably though, he apparently chided Houston for running when Jugger was already a Black candidate in the race.

By all accounts Ford was not implicated in the scandal and Pertee was likely trying to line his own pickets. It had a dramatic conclusion with many of the candidates Pertee tried to solicit money from decided to confront him together. This scandal covered candidates for both seats 1 and 2.

Radio scandal aside, the Seat 1 race was much quieter affair than the Seat 2 contest going on at the same time. Most observers expected Price to win the race, with Houston believed to be the 2nd strongest candidate. Money was far less for Seat 1 vs Seat 2 as well. The finances of candidates for Seat 1 was

Don Price - $985 ($6,000 today)

Daniel Penton - $697 ($4,200 today)

Musa Wali Jugger - $260 ($1,600 today)

Rosa Houston - $40 ($250 today)

Wayne Smith - $7.57 ($50 today)

In previous runs, Houston had brought in much stronger fundraising. However, money all around seemed to be lacking in this contest. The quiet campaign ended on February 12th when Don Price secured 65% of the vote; avoiding a runoff and securing the remaining of Bevis’ term.

Price’s big win was a reflection of voters eager for some stability and the fact Price only had one more year to go for that seat’s term. With the open race for seat 2 being very heated, Price getting the easy not is not surprising. Houston secured strong backing in the Black and student communities she always did well in, but her support in whiter communities remained low. Jugger, meanwhile, took 5% citywide and only got up to 17% in the heavily black precincts. The race was largely a contest between Houston and Price. After the loss, Houston vowed she would remain heavily involved in city affairs and advocacy, but would not run again in 1976.

The End of Old Tallahassee?

So, why did the race for City Council Group 2 dominate the coverage of the 1975 races? It was because the race featured a much starker showdown; all thanks to the entrance of Arvah Hopkins into the race. At the beginning of January that year, Hopkins announced he was running for city council.

The stories I discussed above, and my James Ford supplemental, lay out why this was such a major development. Hopkins’ legacy loomed large in the city; and it was rapidly becoming a divisive legacy. While he had no direct scandals, he was absolutely seen as a reflection of the old small southern town that Tallahassee once was. His ouster as City Manager reflected the changing priorities within the city. However, his decision to run showed he still felt he had more to do. In this contest, which would feature six total candidates, the biggest stand out was attorney Ben Thompson.

Thompson was a young, just 29 at the time, attorney. He’d run for city council in 1972, which I covered in Issue 4. While he’d come in fourth then, he’d raised strong money and impressed observers. He initially said he wouldn’t run in 1975, but changed his mind specifically to stop Hopkins. In this, he set himself up as a generational counterweight to the representative of “old Tallahassee.”

In addition to Hopkins and Thompson, four other candidates ran

W. P. Carrin - local businessman

Ed Hornsby - Former assistant state auditor and current businessman

Rose Moore - Civic activist

Adina Simmons - Economist

Details on all candidates can be seen here.

The race very much became a referendum on Hopkins. The biggest concern was the idea the former city manager would not wield outsized influence with the city management office; especially as Kleman was still getting his footing. The Tallahassee Democrat directly called out that Hopkin’s backers want him in for this reason; even if Hopkins himself simply wanted to serve. Hopkins’ biggest supporters were well-financed and powerful interests, which was reflected in the final fundraising figures.

Arvah Hopkins - $8,906 ($54,000 today)

Ben Thompson - $2,865 ($17,200 today)

Adina Simmons - $2,200 ($13,300 today)

W.P. Carrin Jr - $510 ($3,000 today)

Rose Moore - $5 ($30 today)

Ed Hornsby - $0

Hopkins broke campaign fundraising records with his bid, something that allowed him to heavy campaign, but also led to further questions about conflicts of interest. On top of campaign fundraising, the fact many prominent business leaders had raised a $17,000 fund last summer to help supplement the Hopkins’ retirement fund led to even greater concerns about conflicts.

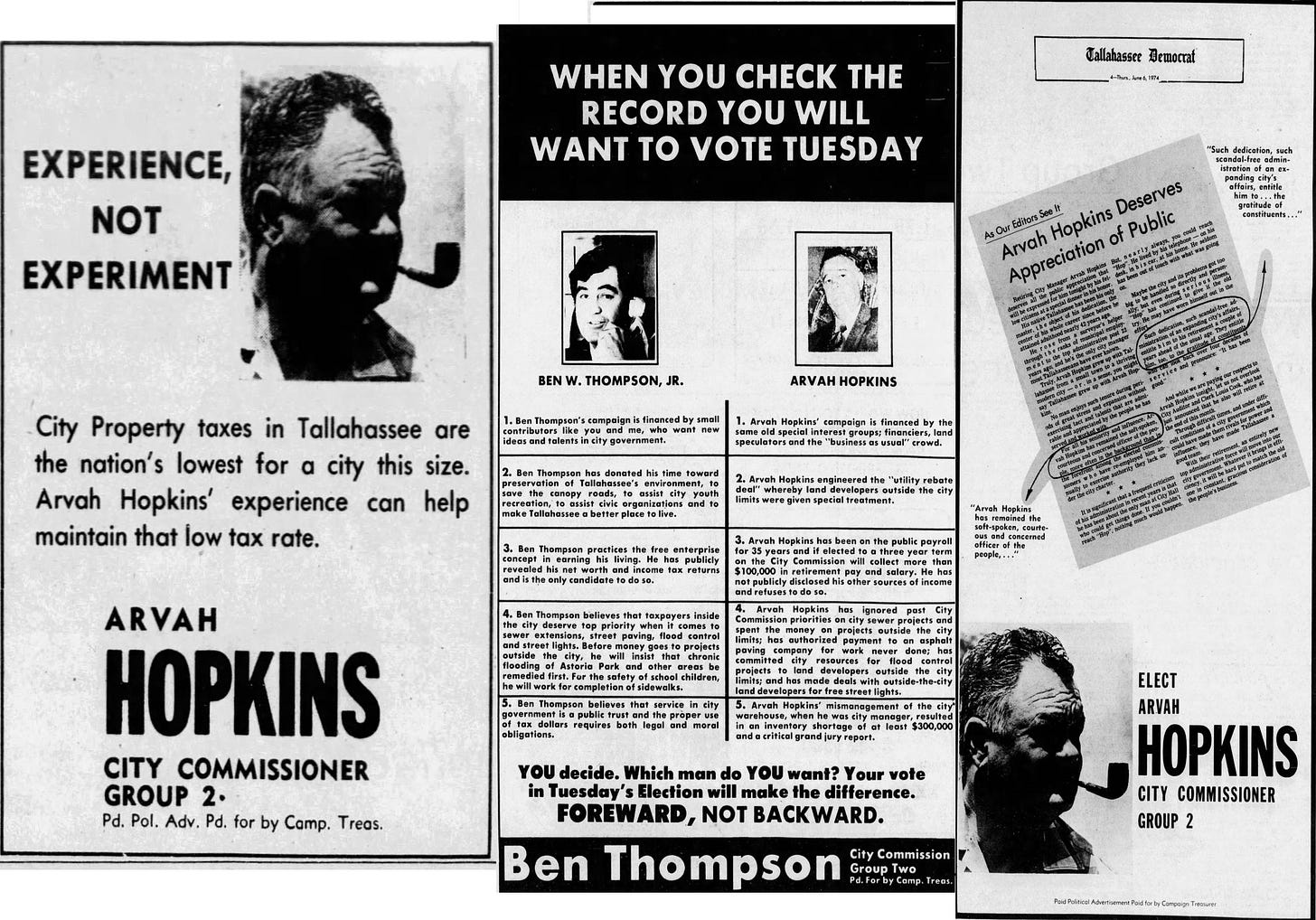

Much of the campaign saw Hopkins being leveled charges by Thompson, Carrin, and Hornsby over past deals and possible conflicts if he was elevated. Meanwhile, Hopkins leaned into his past experiences. The dueling ads in the paper reflect this.

The concerns about Hopkins’ conflicts, even from those who regarded Hopkins well, led to a shock result in the primary. While many Hopkins backers thought he could secure victory in the first round with over 50%, he instead got just 34%, behind Thompson by 7 points.

Adina Simmons, the 3rd best fundraiser, came in third, and was notably stronger in the more diverse west side of the city. Hopkins actually won the heavily Black precincts, but in a split vote with under 40%. Unlike Seat 1, Black voters broadly had no preferred candidate. It was very telling through how well Thompson did in new and “older” Tallahassee. That said, precincts 9 and 8 definitely represented some of the old families.

The runoff was just two weeks later and looking back on it, the Thompson victory to come seems obvious. However, Hopkins backers worked to try and flush the campaign with cash. In the two week runoff, Hopkins raised another $3,900 ($23,500 today) compared with Thompson's $1,600 ($9,600 today). The dynamic of the runoff did not change, however, with the contest seen as a battle between old and new Tallahassee. In the end, new Tallahassee won with 61% of the vote.

Thompson consolidated the backing of most of those defeated in the first round, winning all but the Betton Woods neighborhood. It was a stunning rebuke for the “old Tallahassee.” No one at the time would deny that in a different era, one when the city remained the small southern town it was from Issue 1, that Hopkins would have won. Not only did he lose, he lost bad. This was a new city.

Up Next

This issue did not really delve into race relations nearly as much as previous issues. Originally 1975 was not planned for its own issue in this series. However, I feel the brewing clashes of personalities and finances were too critical to overlook as the city moves into the next set of elections. The 1975 loss of Hopkins also definitely signals a decline in the power of “old Tallahassee.” However, the “New Tallahassee” was still not what we today see as modern Tallahassee. In my next issue, I will cover the 1976 campaign of Harold Knolwes, a young Black attorney that would try to make history as the city’s 2nd Black commissioner. We will see if he succeeded and how this “new Tallahassee” voted.