Issue #184: Tallahassee Series Supplemental: James Ford's Balancing Act

Also lets talk ballot design

Well its mid-June and I am FINALLY getting back to my series on the evolution of Black political power in Tallahassee, Florida. As a refresher, this is a series I began back in February that looks at the political evolution within Florida’s capital city; namely its transition from a small conservative southern town and into a more egalitarian liberal center that it is today. I am telling this story specifically by focusing on the growth in Black political power, from candidates running to voters flexing their power. You can see each article in my series here.

My last issue covered the 1974 elections. This looked at the candidacy of Rosa Houston, a young Black woman who was already well-known for her civic activism and progressive platform. Houston’s candidacy, and her struggles to win Tallahassee office, reflected the still-conservative nature of the town. Houston was a well-accomplished woman, heavily involved in civic programs through her 20s and early 30s. She focused on pushing the city of Tallahassee to be more involved in helping its poorer residents. She spoke up for the inequality that existed in the city’s Black community, which remained heavily segregated due to decades of Jim Crow and racial covenants.

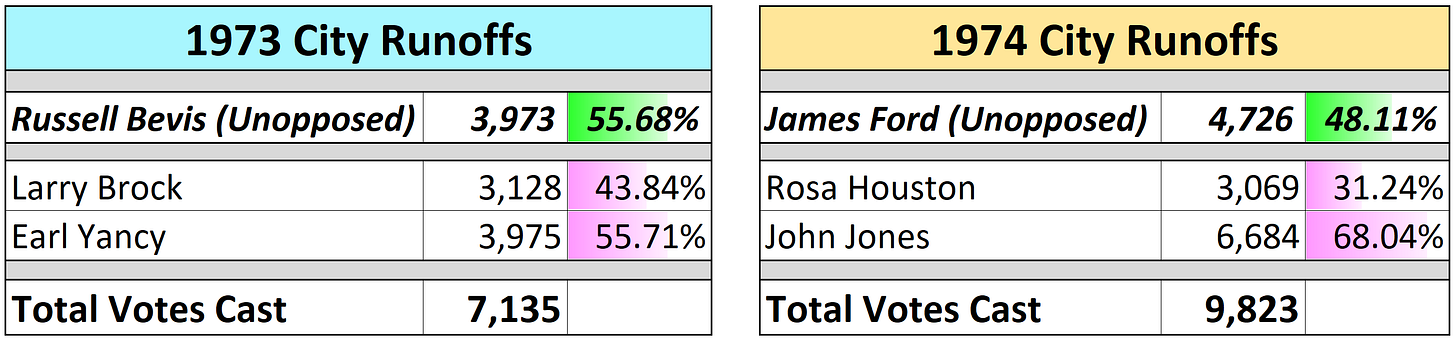

Houston ran for office in 1973 and 1974. In her 1974 race, she made the runoff with Johnny Jones, an older, white longtime city employee. In the crowded first round, both candidate had gotten 22% of the vote. In the runoff, white voters consolidated toward Jones, allowing him to easily win the runoff.

I covered the campaign in detail in Issue 6. I just wanted to set up that important reminder for the rest of this post. That is because this issue is not about the next campaign to take place, but rather is an addendum to this contest that further delves into racial dynamics in the city at the time. This supplemental piece, basically Issue 6.5, centers around Commissioner James Ford.

James Ford’s Balancing Act

The same day that runoff for City Council Seat 2 was taking place, Seat 1 Commissioner James Ford was winning re-election unopposed. Ford, as I discussed in Issue 3, became the city’s FIRST black commissioner since Reconstruction when he won his race in 1971. His election was, rightfully, heralded as a major breakthrough in race relations in the city. However, as I delved into in Issue 3 and onward, Ford’s success was heavily predicated on his ability to not make white voters nervous. Ford lived in the heavily white midtown area of the city, served as a Vice Principle at Leon High School, and per the Tallahassee Democrat editorial board in 1971, was a “good Negro” - aka not someone who only talked about “Black issue.”

“We’ve been saying we’d elect a ‘good Negro’ if one ever ran. Now here’s our chance to prove we aren’t hypocrites” (1971 Editorial endorsing Ford)

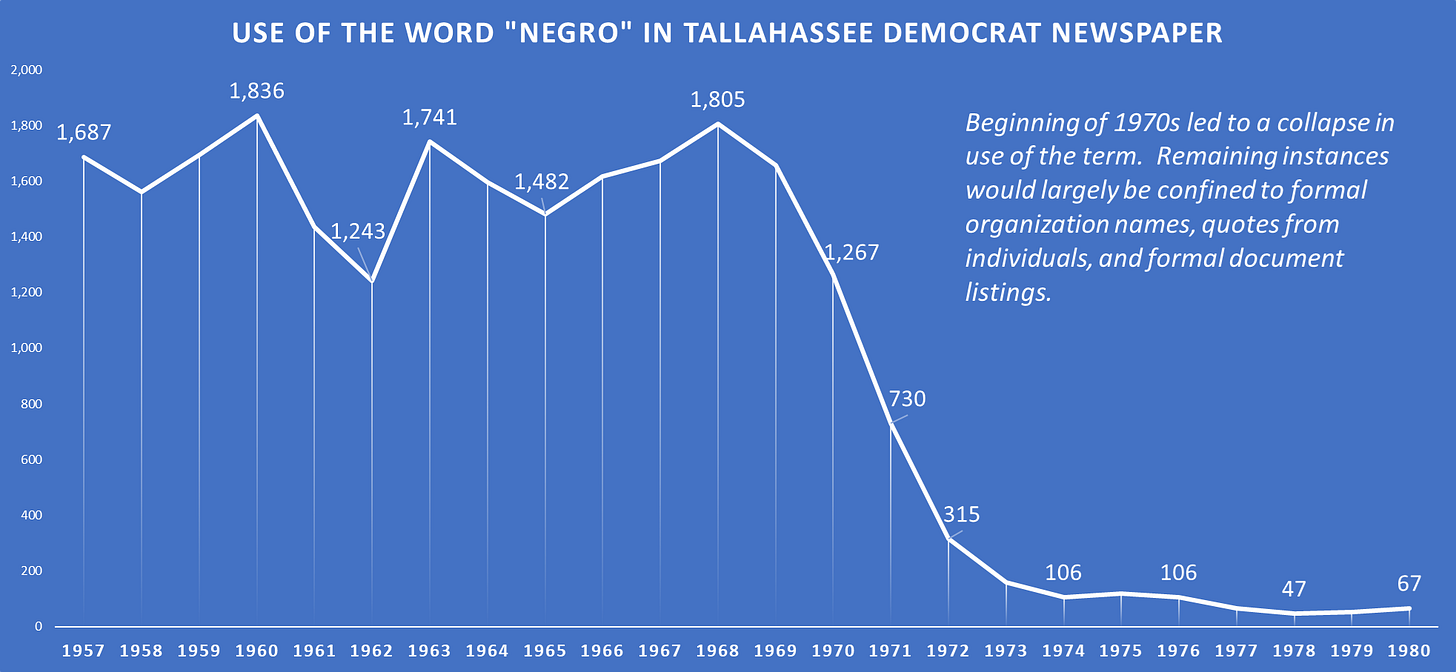

I covered this editorial in my Issue 3 piece, it is as insulting as it sounds. Incidentally this also corresponds with the era where the word “negro” was beginning to fall in usage and instead replaced with “Black.” I actually tracked the use of the word over the years in the Tallahassee Democrat archives.

This was the environment as Ford came into office. As such, he would spend his tenure as a commissioner with a sometimes love-frustration dynamic with the city’s broader Black community. Ford would stand up on racial issues plenty of times, but was also definitely part of the city’s “good ol boy” network. During his time on the city commission, Ford would serve as President of the Tallahassee Urban League and serve on the board of the local Chamber of Congress. Commissioner Ford would often be found with his colleagues and other elected officials at different events. Many in the Black community grumbled about Ford being too friendly with an establishment that didn’t bring enough resources into their community.

All this said, I don’t want to frame things as if Ford did not serve as an advocate for the city’s Black community. Several issues would see Ford taking a leading role on many issues. For one, Ford was an outspoken advocate for more diversity within the city political structure. One example from 1974 saw Ford advocate the need to get a Black member on the City Planning Commission. When commissioners instead went with a white applicant, Ford abstained, making a point that he felt the commission needed “ethnic representation.”

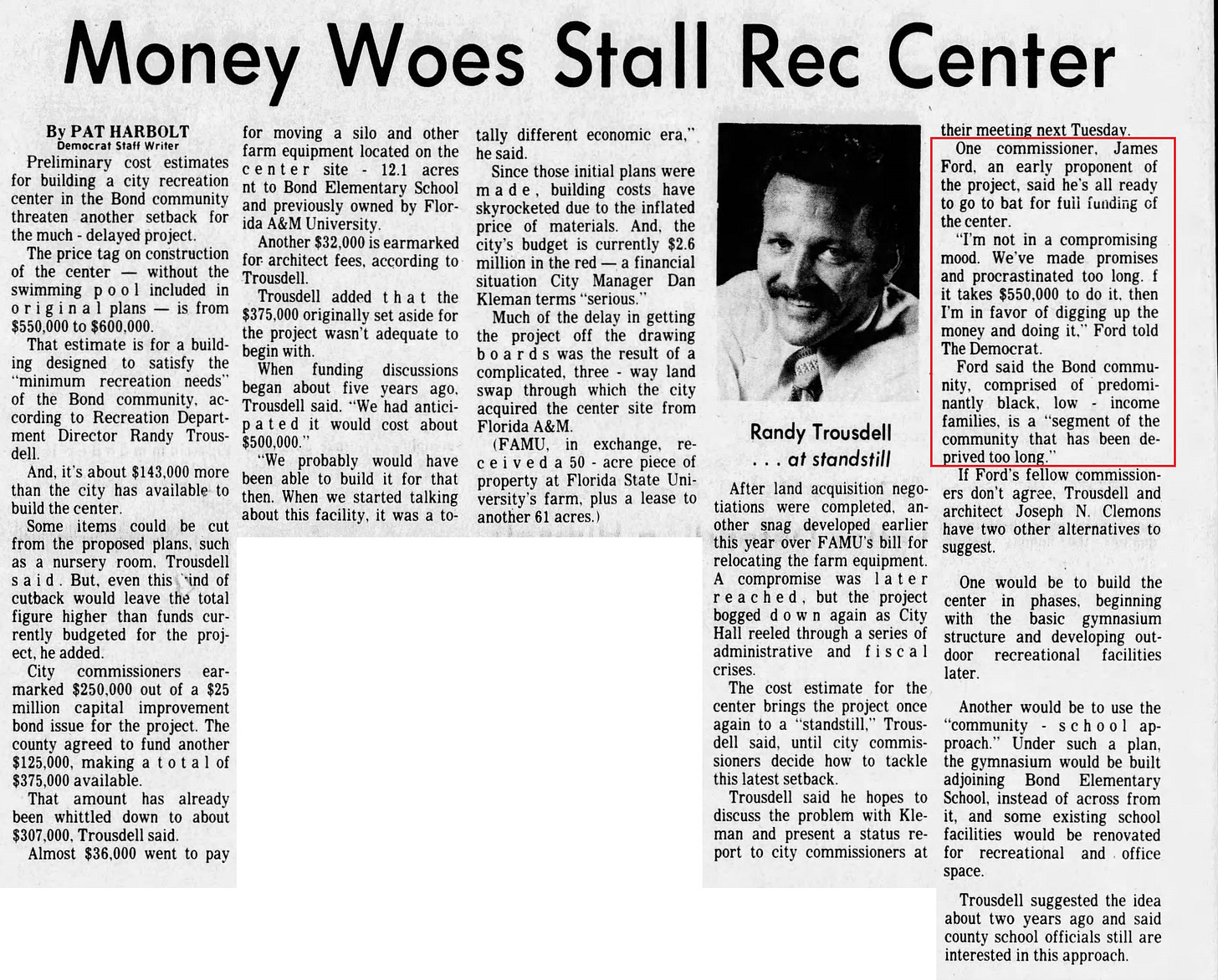

A major issue that Ford took a strong position on was a community center for the Bond community; which was/is a heavily Black community in the southside of the city. The project was a long debating point through the early to mid 1970s, with concerns about costs and the city budget often delaying the progress. Ford, however, said any cost was worth it, as this was an area in sore need of such a center. Ford described Bond as a “community that has been deprived too long.”

The Bond community center would be completed in 1976, partly thanks to Ford never letting the issue die or shrink as budget questions constantly arose.

Ford clearly did have an eye for guiding Tallahassee into a more active and progressive era. He was a major champion of bringing in Daniel Kleman as the new City Manager in 1974. This post became open when the longtime manager, Arvah Hopkins, decided to step down. The change reflected a major shift in city government, as Hopkins represented an era of Tallahassee as a small southern town. Kleman, a 28 year old deputy city manager of Dayton Ohio when he was picked, spoke about a more active city government. Ford was the commissioner to officially nominated Kleman, and was viewed a major ally of the manager through the decade. There is far more to say about Hopkins and Kleman, which I will cover in my next issue. One issue Kleman made clear he was an advocate for was affirmative action; an issue that quickly became a major point of contention in the city.

Tallahassee Sued by the DOJ

Like countless governments and private businesses through the 1970s, the issue of Affirmative Action regarding employment was a major topic. The debate in Tallahassee came as reports painted a damning picture of the city’s hiring practices. A 1974 study showed that the Tallahassee Government used Black workers for manual jobs, but rarely gave any manager positions. A report from the Florida Commission in Human Relations showed…

69% of the the city’s 309 day laborers were Black, but 95% of managers were white

History existed to show promotions from within was rare, with new white leaders brought in when management or supervisory positions opened up

Black men made just $4,500 a year compared with $7,400 for white men

Women made just $5,300 a year on average, with less of a racial disparity

Women were still largely relegated to clerical and non-managerial roles

The report did commend the city for recent efforts to improve hiring practices. Before the study had been released, Kleman had discussed the importance of improved affirmative action within city departments. This was also a major issue for James Ford, and it would become a major concern at the end of 1974 when the US Justice Department announced it was suing the city for its discriminatory hiring practices.

The lawsuit was expected, but it was noted that in the last few months of 1974, the city had been working to improve its practices. Kleman was outspoken on the importance he placed on Affirmative Action.

The city was able to come to a settlement with the DOJ in the spring of 1975. As part of the settlement, the city creating an Equal Employment Office to review practices, and mandated quotas for new hiring; namely that 50% of all new hires in all departments must be to a qualified Black applicant. This would be in place until a proportion of black employees matched the demographics of the city. Issues around employment would be ongoing through the rest of the decade. By 1978, there would still be criticisms about the lack of advancement into managerial posts for many Black employees, but the city was able to point to notable improvements in hiring practices.

Through the many years of debate and review of the affirmative action process, Commissioner Ford would be a voice for improved hiring practices whenever he felt they were lagging. He would do this with a deftness, however, rarely being antagonistic when it could be avoided.

1974 Ballot Confusion?

Considering Ford’s balancing act, its not entirely shocking he was re-elected without opposition. He’d done nothing to really anger voters in the white communities, and any frustration from black civic leaders wasn’t enough to warrant not supporting him.

Once he was officially unopposed in his 1974 re-election, Ford’s campaign spent some of the money on a newspaper advertisement thanking the voters for their faith in his service.

While Ford was unopposed, he would actually still be on the runoff ballot. Election laws for the time stipulated that unopposed candidates still appeared on the ballot during the runoff campaign. Voters would only be able to vote for Ford, and realistically he just needed 1 official vote to be “formally” re-elected. That would of course happened in the runoffs, with Ford getting thousands of votes. The coverage was 100% focused on the Jones v Houston race.

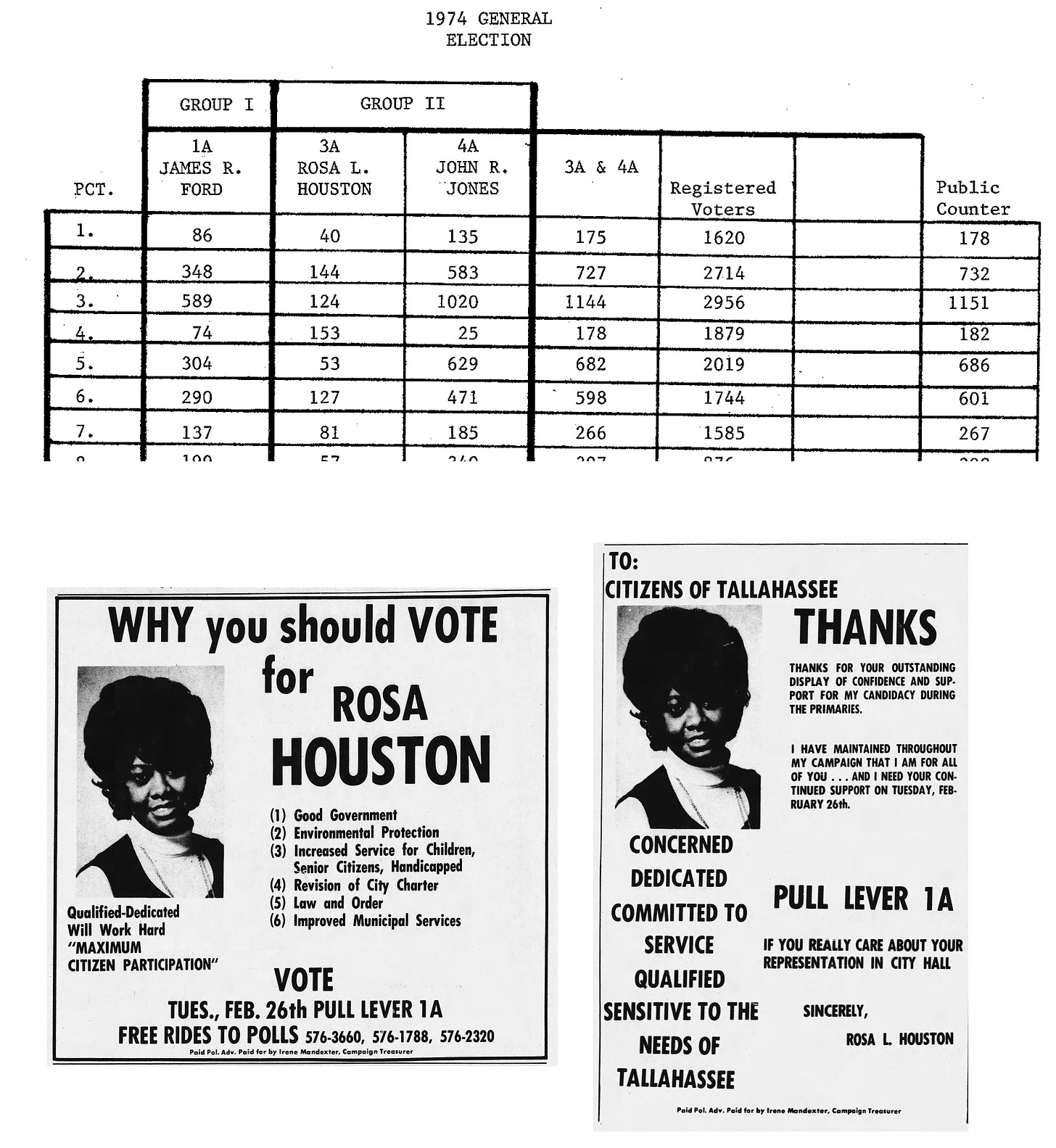

However, Ford’s place on the ballot led to a moment of confusion. As you can see below, the way the ballots were structured, Lever 1A (back in the days of the old voting booth machines) was designated for James Ford in his race. Rosa Houston was 3A and John Jones was 4A. However, Rosa Houston’s ads leading up to the runoff told voters to pull lever 1A for her.

The mix-up was thanks to Houston being unaware Ford would be on the ballot at all. This is not a shock, as it was not a well-reported or covered process. Also remember that the time between the primary and runoff was just one week. These Houston ads were likely produced quick to get to the Tallahassee newspaper in time. Its an unfortunate error and while yes the burden is on the candidate to get things right, it is also easy to see how such a mistake could happen.

As a the results were announced, Rosa Houston was very upset to find out about the Ford 1A slot. She pointed out, correctly, the city had not produced sample ballots ahead of time. She speculated that folks may have pull the lever for Ford thinking they were pulling it for her. She lost the race by 3,600 votes while Ford took in 4,700. Could that have been the difference? Should Houston have won? Well lets run the numbers.

The Ford Ballots

Spoilers, the Ford vote was not a mistake that should have gone to Houston. This is pretty apparent when looking at how Ford did compared to previously unopposed candidates. In this case, I looked at the 1973 city contests. In that runoff, which saw Earl Yancy defeat Larry Brock for one of the seats, Russell Bevis ran unopposed for a different seat. Bevis got 3,900 votes that year, or 56% of the total votes cast; so 46% left that seat blank. If we compare this to Ford in 1974, his 4,700 ballots is just 48% of the total cast.

Ford’s 48%, meaning 52% of voters just left 1A un-pulled, was already below Bevis’ share. His total certainly isn’t inflated in a way that we’d assume if he accidently got thousands of additional votes from Houston backers.

In fact, we have the data on how many people showed up and voted just for Ford before leaving. This is gotten by taking the total turnout and subtracting the total ballots cast for the contested city race. If thousands of Houston voters accidently pulled 1A thinking it was for her, then the Ford-only vote should be in the thousands. Instead the Ford-only vote was just 70. That vote was highest, up to 2.5% of ballots cast, in Frenchtown, but was under 1% in most of the city. I likewise also looked at Ford vs Blank, and nothing in the precinct data indicates an inflated vote share in specific areas strong for Houston.

The data definitely does not point to thousands, or even hundreds, of mistaken Ford votes meant for Houston. If such an event occurred, we’d see higher Ford shares and higher Ford-only votes in specific precincts.

Houston likely realized this was the case fairly quickly. After her initial frustration on election night, the issue did not come up again. She would remain active through the rest of the year, with the city making some election reforms for the 1975 contests. I will cover that more in my next piece.

Final Thoughts

Numbers aside, its also easy to see why every Ford voter would not automatically be a Houston voter. Ford had a broader base of support due to his style of of politics. His unopposed re-election the same day Houston went down 2-1 shows how the city was not opposed to electing Black candidates, but it was warry about many Black issues. As I discussed in Issues 4, 5, and 6, Black candidates who didn’t operate like Ford often got labeled as the “Black issues candidate” - which killed them in the white parts of the city.

Ford was a groundbreaking official. He paved the way for future Black candidates and eventually future Black commissioners. However, the numbers and stories from this era still show the city was not willing to entertain more “active” Black advocates.

We will see how that dynamic evolves as I move into the mid to late 1970s.