Issue #109: Emancipation Day in Florida and the Broken Promises to Freed Slaves

A look at the end of slavery and rocky reconstruction

Today, May 20th, marks Emancipation Day in Florida. This marks the anniversary of Union General General Edward McCook reading the Emancipation Proclamation from from the steps of the Knott Building in Tallahassee in 1865; marking the end of slavery in the state.

Many jurisdictions in the state celebrate both May 20th and June 19th (Juneteenth) as days that commemorate the end of slavery. In recent years, a big push in Florida has begun to give attention to May 20th. This kicked off in 2021 when Leon County and Tallahassee, the site of the historic reading on the court steps, recognized May 20th as a formal county holiday.

In honor of this date, I wanted to dedicate a post to looking at the end of slavery in Florida and the fight for reconstruction. Sadly, like a vast majority of the nation, the joy of the end of slavery in Florida eventually led to the rise of Jim Crow. Much was promised on May 20th in 1865 - and Florida has never lived up to those promises.

Slavery and the Civil War

I have written about Florida’s politics leading up to the Civil War and the debate over secession in the past. I won’t go deep into all the details here, but I recommend giving my “Florida Secedes from the Union” article a read.

Suffice to say, Florida was like many of the southern states for its time. It held a large slave population, largely concentrated in the north, and had spent the 1850s becoming more radical on the issue around slavery.

Florida was full of wealthy plantations in its Northern counties.

Florida elected two “fire-eater” Democrats as Governor in 1856 and 1860. The fire-eaters were pro-slavery politicians who refused to compromise on the issue and constantly threatened secession.

In 1860, John Milton was elected Governor. He was a secession supporter and would be a feverish confederate through the war.

After Lincoln’s election, Florida would become the 3rd state to secede from the union. I covered that convention and its politics in depth in my secession article. Florida was a big supplier of goods and food for the war, but did not see more than a handful of battles itself. As it became clear that the war was lost, Governor Milton, in his final message to the legislature, said that the Northern Army “have developed a character so odious that death would be preferable to reunion with them.” He would soon leave the capital to return to his home in Jackson county.

Then, on April 1st, 1865, Governor Milton committed suicide by gunshot.

In what might be the only case of an incumbent Governor committing suicide in the country, Milton took his own life in his barn rather than face surrender and likely imprisonment. There has been some effort to claim the shooting was an accident when Milton was cleaning his rifle. This, however, is a family claim that comes up years later and also implies an experienced gunman didn’t know how to properly clean his weapon. Many friends of Milton testified to the Governor’s deepening depression as the war went bad, and there was a resigned acceptance at the time of his death that it was a suicide.

On May 10th, confederate troops surrendered to the union in Tallahassee. May 20th marked the reading the Emancipation Proclamation on the Knott Building steps.

The Fight for Reconstruction and Voting Rights

The end of slavery in Florida, like many southern states, was quickly met with white resistance. Unfortunately for the newly freed slaves, the assasination of Abraham Lincoln put Andrew Johnson in the Presidency. His plan of letting the former confederates re-enter the union on their own terms spelled disaster for the freedmen.

In 1865, President Johnson appointed William Marvin as acting governor of Florida. The goal was to get a new constitution in place, largely just removing secession and slavery. Marvin was not a supporter of giving the vote to freed slaves. Already that year, some local communities, namely Fernandina, had seen newly freed black voters go to the polls for local races. The goal of Marvin and others was to restore white rule. Marvin himself said that giving the slaves freedom does not mean they were ready for the “privilege” of voting.

The elections held for delegates to the 1865 Constitutional Convention did not allow black people to vote. In the end, the delegates of that convention passed a document that enshrined voting only for white people. That November, David Walker was elected Governor. During his tenure, Walker was dealing with the likelihood that the Republican Congress, especially after their 1866 midterm landslides, would impose new rules on the south. Walker and many took the stance that they would rather have no civilian government than have one that allowed black people to vote.

In 1867, the Republicans in Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, which forced the southern states to reorganize and give rights to the newly freed slaves. This led to the voter rolls being opened to freed slaves, as well as the removal of ex-confederate.

The Reconstruction Era

Under federal watch, Florida held November 1887 elections for a new constitutional convention. The voter rolls showed a majority of those registered in Florida were newly-freed black Americans.

The vote on holding a constitutional convention was held the same day as delegate races. The returns for a constitution are incomplete, but were declared to have passed. Opponents of a new constitution boycotted the vote, with only a handful registering formal opposition.

The delegate elections, as reported by the local papers, broke down as follows. These I believe are missing 3 delegates. However, results for this time are patchy.

The results of the elections were a majority that favored more aggressive rights for the newly-freed slaves. However, the document that would come out of this convention would be far less progressive than it should have been. This was due to the efforts of both Confederate sympathizers and more conservative Republicans to limit the power of black leaders. I covered this in my article on Reapportionment and Redistricting in Early Florida. The following text in italics comes straight from that article.

General John Pope ordered delegate elections for a new constitutional convention, which subsequently met in January of 1868. Of the 46 delegates, 18 were black and 28 were white. A coalition of black members and radical republican white members made up a majority; known as the “radicals.” A faction of “moderates” – made up largely of white planters and business interests, were a minority at the convention. Once the “moderates” realized they were a minority at the convention, they tried to delay the actions of the body for weeks as they plotted with former Confederates to overthrow the leaders.

Apportionment became a major fight at this convention. The “moderates” wanted a system that gave equal county weight – a system that would benefit the small but numerous rural, white counties. The former plantation counties, many now with voting black majorities, were the biggest voting blocks in the state. As such, the “radical” faction at the convention favored apportionment with more of a population emphasis. The fight over apportionment by county vs population became a def-facto fight between black and white.

The “moderates”, realizing they couldn’t win fairly, left the Tallahassee convention and travelled to Monticello, some 25 miles away. There, they passed their own constitution, which gave each county one state house member and allowed a county to have an additional member for every 1,000 registered voters (not census count). No county could have more than four members. The State Senate would be single-member districts and supposed to be equal in population “when feasible.” The “moderate” faction then returned to Tallahassee, kidnapped two “radical members” in order to get a quorum, went to the convention hall at night, and “passed” their constitution. This was all done with the aid of federal troops stationed at the capital. Eventually the “radical” majority was able to pass its own constitution, but the reconstruction committee in DC picked the “moderate” constitution. Future Governor Harrison Reed, a moderate Republican politicians, wrote to former Democratic Senator and pro-Confederate David Yulee

“Under our Constitution the Judiciary & State officers will be appointed & the apportionment will prevent a negro legislature.”

This constitution, passed under nefarious means, aimed to limit black power to the benefit of white Republicans in many additional ways. Most notably was the power of the Governor to appoint ALL local officials at the county level. This means the majority-black counties could not decide for themselves who would be their commissioners, appraisers, or county clerks.

The measure also did allow for restrictions in voting rights. Education limits could be set and criminal convictions could deny someone the vote. At times these rules were enforced selectively, and often were used to essentially keep black voters in line with the white Republican leaders.

In the 1868 Elections, held in May, Harrison Reed won the Governorship. He largely had the backing of former slaves. However, black voters in Tallahassee, Jacksonville, and Fernandina backed Radical Republican Samuel Walker. Even this split resulted in an easy Republican win thanks to the empowerment of black voting and many ex-confederates still being off the voter rolls.

The same day the constitution was approved, and its vote matched the Gubernatorial contest almost perfectly. Backers of the Democrat for Governor rejected the measure for expanding black rights, while black voters supporting Walker rejected the constitution as well for short-circuiting bigger advances.

The elections began an 8 year period of Republican rule in the state Governorship. However, as the late 1860s and early 1870s went on, the Democratic party in Florida began to rebuild. Meanwhile, Republicans were divided between radicals that favored more black rights and the conservatives who wanted to maintain their own rule. In counties like Jackson, mass violence was used to stop black people from voting. Governor Reed’s solution was to appoint white leaders to county posts who would uphold white supremacy but stop the lynchings. The truth was, folks like Reed were more willing to buy off ex-confederates and the Klan.

In 1872, Republicans held the Governorship with Ossian B. Hart, a former slave owner. For black voters, sticking with the modest advancements under these white leaders was the best option versus the terror of many Democratic leaders. However, with many black voters continuing to be intimidated away from voting, or restricted by the 1868 constitutions restrictions, Democrats began to slowly gain control in Florida. In 1874, Democrats took control of the State House and the State Senate became a tie. Then in 1876, Democrats won the Gubernatorial Election, a win that came amid a massive divide between Republican leaders.

This win came during the contentious and controversial 1876 Presidential Election. While Florida would eventually be declared for Republican Rutherford B Hayes, the mix of fraud and violence is so severe that it is legit impossible to know who really won the vote. Granted the same is likely true for Governor.

The Republican rule of Florida came to an end with 1876. Much of the last eight years had been spent with these leaders using black voters to keep their power while limiting the full advancement of the freed slaves. The flip of the Governor’s post meant that Governor Drew could now appoint all local county leaders. This led to the mass appointment of Democrats to lead majority-black counties. With this sea change, violence also increased to intimidate black voters. Fraud against black voters also increased.

The Rise of Jim Crow

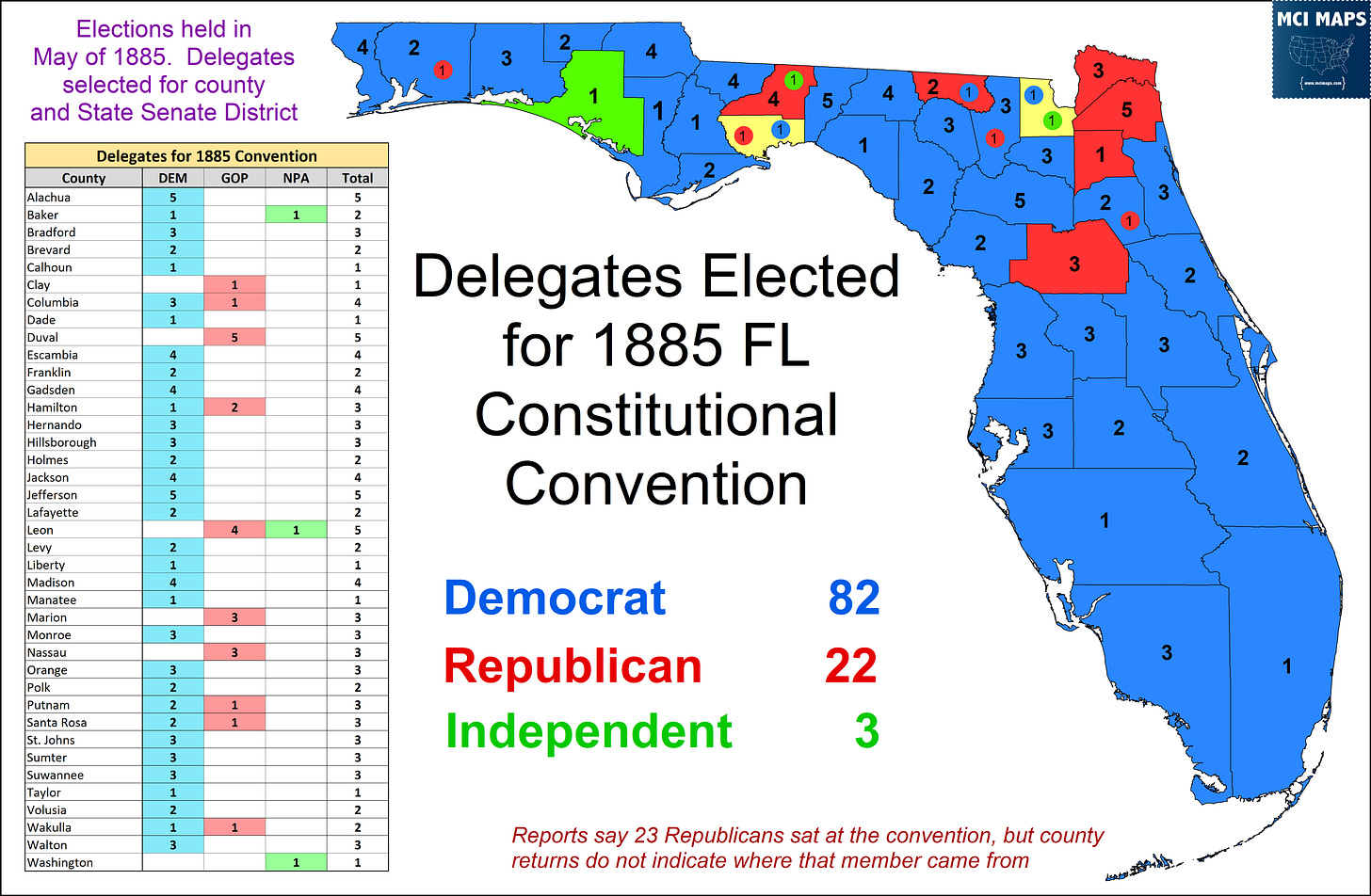

The next several years would would mark a continued solidification of Democratic rule. This culminated with the push for a new constitutional convention. In 1885, delegate elections were called. By this point, Democrats were guaranteed to control the convention, and many black and Republican voters debated whether to back moderate Democrats to at least have an influence. Discussions about fusion voting were successful some places, but in many areas the black voters did not want to side with Democrats. In many counties, intimidation was used to keep black voters from coming to the polls.

The convention itself only had 7 black delegates. The delegates worked to cement white rule by including a poll tax provision, keeping several other voting restrictions from 1868 in place, affirming segregation, and allowing the election of local officials except for county commissioners. Some black delegates supported the local elections, hoping it would give some power. However, eventual uses of poll taxes and more intimidation would negate that gain. Commission elections would eventually come in future years, well after white rule was absolute.

In the 1886 elections, the constitution was approved with 60% of the vote. Intimidation kept many voters away from the polls. Ballot stuffing and threats of job losses were also common tactics.

With the new constitution taking effect after the 1888 elections, the Democratic leadership of Florida was able to pass several methods of restricting black voting. These includes

A poll tax that disenfranchised black voters and many poor whites

“Multi-box voting” - a system where voters needed to put certain ballots in certain numbered boxes. This severely hurt the illiterate, which was about 40% of black voters.

Different polling stations for state and federal elections, aimed at confusing voters

Eventual adoption in the 1890s of a party primary, which was closed only to whites

The poll tax was passed in 1889, and its effects are clear cut. The 1876-1884 Presidential Elections in Florida had been close, but even by 1888 the gap was widening. However, the poll tax and other methods gutted black voting power so bad that in 1892, Republican were so decimated that they opted to side with the Populist Party. When they returned to the ballot in 1896, a big Republican landslide year, they were a non-factor in Florida.

This marks the final transition to Jim Crow. Florida would remain a one party state for the next several decades.

It wouldn’t be until the Civil Rights era that black voters would begin to re-emerge as a political force in Florida.

So as we celebrate Emancipation Day and upcoming Juneteenth, we cannot forget the broken promises and short-won voting rights that black voters across the south were subject too.

Of course, you may not see much of this history in any Florida school books for awhile.