Issue #148: On This Day in 1861 - Florida amid the Secession Crisis

The 3rd State to leave the Union

On this day (January 10th) in 1861, Florida seceded from the union. This action came after a week of a secession convention in the state debating proposals on the matter. In the end, Florida’s convention would opt to secede by a vote of 62-7.

I have written about Florida’s road to secession before. A 2018 article of mine delves deep into Florida’s pathway to disunion and the convention roll calls themselves. You can read a much more detailed account below.

Florida Secession Convention Article

While that link will provide a much more detailed look at the debate in Florida, I do want to use this edition to go over some key points - and look at how Florida’s secession tied in with other state actions at the same time.

Why Florida Seceded

From Florida’s rise to statehood until 1860, it remained a committed southern slave state. The population of slaves was heavy in the state’s Northern panhandle, with prominent plantations dotting the region. Florida expressed a fierce pro-slavery and anti-black sentiment when congressional debate emerged during its statehood push over a provision in the territorial constitution that banned free black people from moving to the state. By the time of the war, very few free black people resided in Florida.

From the 1850s and to the civil war, Florida would consistently elect fierce pro-slavery politicians. In the 1856 Gubernatorial contest, Madison S. Perry was elected Governor. Perry was a fire-eater, aka someone who favored secession to defend slavery. He narrowly beat David Walker, who had the backing of remaining Whigs and Know-nothings, and favored staying in the union but also defended slavery.

The major difference between Perry and Walker was how aggressive Perry was on secession even at that time. The 1856 Presidential election was taking place, and the prospect of a win by Republican John C Freemont led to calls for secession if such a move came to pass. Perry backed secession if needed to spare Florida “black Republican rule.”

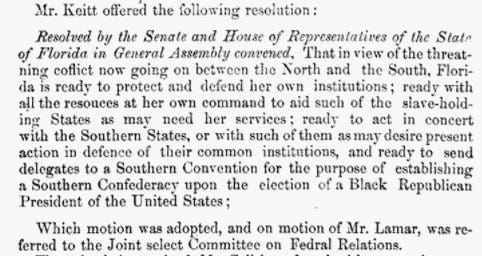

The election of Buchanan to the Presidency held of the secession crisis, but Perry and other southern politicians readied for an eventual split. In 1859, the Florida legislature unanimously passed a resolution pledging support for any states that would secede.

The resolution, and non-stop statements from politicians of the time, showed slavery was the main driver for any secession talk.

In 1860, Florida held its next Gubernatorial election. Secession was the main issue of the campaign, with fellow fire-eater Democrat John Milton defeating Constitutional Union candidate Edward Hopkins.

This result ensured the fire-eater Perry would be replaced by a similar secessionist.

The Presidential results one month later led to immediate calls for secession. Governor Perry and Governor-elect Milton backed calls for leaving the union, raising a militia, and calling a convention. Perry’s call for the legislature to pass a bill for delegate elections to a convention debating secession was passed; with December 22nd being the date of the vote. The result of these elections would likely decide if the convention would vote to secede or remain in the union.

To this day, full reports of these election results remain lost (if they were every centralized at all). Historians estimate that secession did have its opposition in the state, best seen by support for the non-Democrats in the Gubernatorial contests. However, most delegate races, as the above paper clipping shows, were unopposed. Unionists who would flee the state reported that most anti-secession voters were afraid to campaign, with the state apparatus firmly in the secession camp.

The election results may not be available, but we have detailed looks at how delegates voted at the convention. I delve much more into this in my longer article, but several votes from the convention, which began January 3rd, showed where more compromise or delay-minded delegates lie.

Different votes that split the convention between a Cooperationist (this is a broad group for those who did not favor immediate secession) and the Secessionists (who wanted no delay). Several votes on waiting for other states to act, or for a referendum to be held, failed, but showed where the fault-lines were.

Looking at all the votes, I took effort to categorize each county delegation at the convention by how it fell into the Cooperationist and Secessionist camps.

I lay out my methodology much more in my main article. Many delegations were clearly nervous about rushing to secession despite the calls from state leaders. In the debate within Florida, but other states as well, there were many concerns about the economic damage of a war, and the worry the south could not win. In many instances, plantation families did not want secession, as they saw a war as disastrous.

In the end, efforts to compromise or delay failed, and many of the cooperationists opted to vote to secede when all efforts failed. The final vote was was January 10th, making Florida the 3rd state to secede, one day after Mississippi.

The Actions of Other States

Florida’s push for secession was, as we all know, hardly unique. Florida was the 3rd state to secede, but it was part of an even larger effort to leave the union. The early states would leave via convention rather than popular referendum. As a result, the short-noticed elections for the delegates were the major fight.

First was South Carolina, which quickly moved to hold delegate elections scheduled for December 6th. We clearly know that all the delegates elected would be secessionist, as its final vote at the convention was 169-0. However, a full roster of results, like Florida, proves illusive as of this writing. Newspaper reports do indicate that broadly only secessionists were running in many areas, while unionists slates were getting under 5% of the vote. This clipping from the December 10th Charleston Courier shows some reported results.

South Carolina’s convention voted to leave on December 20th; making it the first to formally secede.

The next state to hold delegates elections was Mississippi, which went to the polls on December 20th, just two days before Florida. We do have detailed returns here, which show that secessionists won 61% of the vote.

Opposition, similar to Florida, was a mix of unionists but also folks who favored a delay to coordinate southern efforts. The “cooperationist” camp was also filled with many members, often from the planter class, that saw a war as economically disastrous. They’d be proven right in the long term.

On December 24th, two days after Florida, Alabama would hold its delegate elections for a convention. Here we saw a 56% win for the strict secessionist crowd, who favored an immediate leaving. The state produced a geographically-divided map.

The geographic divide is two fold. The Northern counties were less slave-dominated; though don’t be mistaken we are seeing several slave-heavy counties vote Cooperationist. Another factor was exposure. Many cooperationists worried about being exposed to Northern troops if a war broke out. With Tennessee, North Carolina, Kentucky, and many other middle-south states unclear on their path in the crisis, North Alabama leaders worried Tennessee would be a prime location for federal troops to march in.

These concerns fell away to rigid anti-North sentiment, with Alabama’s convention voting on January 11th to secede. The final vote was 61-39, with many northern counties remaining concerned.

On January 2nd, one day before the Florida convention began, George held its delegate elections. Secessionists would narrowly win the popular vote, but secure a decent majority of the delegation.

I’ve actually written about the George secession crisis in this article here. In it, I work to dispel an old myth about rural Dade County (NW corner of state) seceded from Georgia when Georgia took too long to secede.

I’d read more there for info on the Georgia campaign. In the end, Georgia would secede by a vote of 208-89 on January 19th. This also highlights, like Florida, that many cooperationist delegates would eventually opt for secession when compromises failed.

These three states all held elections before Florida began its convention. No doubt the reports of the secessionist majorities helped fuel the efforts at the Florida convention. The delegates no doubt had wind of the results, as the capital was filled with pro-secession leaders reporting the latest. Accounts of the Georgia returns being spread in the first few days of the convention show up in correspondences.

To the Florida delegates, they’d see a wall of neighbors supporting leaving the union; no doubt aiding in defeating those delay roll calls.

Before Florida’s convention was finished, another state went to the polls for delegate elections. Louisiana would hold delegates elections on January 7th. Like Georgia, the popular vote was not overwhelming, but the delegate breakdown was solid for the secessionist camp.

Louisiana also notably held elections at the parish/house level and at the state senate level.

Louisiana would vote to leave on January 26th, with Texas following on February 1st. These would be the seven states in the confederacy when the attack on Fort Sumter began; formally starting the Civil War.

Some great history here. Thanks, Matt.

Georgia also. Obviously Alexander Stephens had been a Whig!