On Tuesday, I released the first part in my series on democracy in Hong Kong. That issue covered early elections in the former-UK province, and the tense transition toward handover to China in 1997. Read that post for important background information.

When we entered the handover period, the population of Hong Kong was largely divided into two camps.

Pro-Democracy Parties - Organizations that favored more freedom of voting and were constantly suspicious of any interference from Beijing on democratic or cultural matters

Pro-Beijing Parties - Heavily dominated by business interests, these organizations wanted to maintain the status quo, which largely saw the Chinese Government allow capitalism to continue. To them, increasing voting rights or social fights was not worth antagonizing the CCP and risking instability.

For the years post-holdover, Hong Kong would be in a constant state of tension with China, with efforts to maintain the promised autonomy continuing. The Tiananmen square massacre caused a great fear within the province about what a holdover from the UK would mean. This led to a constant pro-democracy force within the population that would protest and fight against over-reach by Beijing. This was in conflict with an election system that aimed to benefit the pro-Beijing business interests.

This would culminate with pro-Democracy landslides in 2019 and a followed-up crackdown by Beijing that today leaves the area with no true elections.

This newsletter will cover the period from the UK handover in 1997 and into 2019, setting the stage for the 2019 saga.

Hong Kong’s Democracy Post-Handover

In 1995, Hong Kong, while still a province of the UK, passed expanded election reform that made the 1995 Legislative Elections the most democratic in the provinces history. (Read Part 1 for more details.) Those reforms angered China, which did not favor more democratic rights than had already been instituted in the early 1990s. While the initial agreement was that the 1995 legislature would continue in power once the handover happed, the reforms caused China to cancel that agreement. As a result, in 1996, a Provisional Legislature was set up in the mainland that would then oversee the 1997 handover.

Once the 1997 handover in Hong Kong took place, the provisional legislature worked to make changes to the election laws. New legislative elections would be held in 1998 and local councils in 1999. Beijing knew that it could not go too far in rolling-back the reforms - as it wanted to maintain good relations with the international community. At the time, Hong Kong’s economic boom also meant it was a major economic driver for the country. The instability of massive protests from a complete crackdown on elections was not desirable. The major election changes were designed to allow democracy, but with it controlled to ensure pro-Beijing forces maintained power.

The combination of reforms; as well as laws already in place via the Basic Law (the provinces constitution) set up the system largely in place for the next 20 years. I’ll break each critical post down below.

The Chief Executive & The Election Committee

The most powerful post in Hong Kong is the Chief Executive. Acting like a Premier, Governor, or President, this individual is not directly elected by the people. Instead, the Executive is chosen by the Election Committee.

So what is the election committee? From 1998 to 2012, it was an 800 person organization elected by only a small segment of society. In 2012, it was expanded to 1200. A vast majority of the committee is elected by functional constituencies made up of business guilds, unions, and interests. One of the reforms Beijing passed was moving much of the functional constituency voting back to the bosses/leaders, and less to the average works. These elections weigh heavily in favor of pro-Beijing interests. Other members include people appointed by party leaders, members of the legislative council, and religious institutions. The incredibly complicated mix of elections for the committee can be found here.

A good video on the pre-2021 crackdown method is here. As it details, only 3% of the Hong Kong population were able to vote via different functional constituencies.

Through every election, the pro-Beijing candidates always dominated votes for the committee and hence for the Chief Executive. The winner of every executive race was a pro-Beijing candidate. It was not until 2007 that candidates determined to be pro-democracy even ran and none came close to winning.

The Legislative Council

The legislative council serves as the main rule-making body in Hong Kong.

The biggest changes from Beijing after the holdover were for legislative council elections. While the outgoing UK government had democratized these elections more, the provisional legislature scaled back these changes.

First - The Geographic constituencies were changed from single-member districts to proportional representation in five different districts. The system used specifically was the “largest remainder method” and utilizing the “Hare quota” system. Now if you aren’t a political scientist, that probably meant nothing to you. Long story short, it is a system that aids low-performing parties, often ensuring a seat after passing a pre-set % threshold. This system was used to aid the less-popular pro-Beijing parties and limited the domination pro-Democracy groups could wield. This meant that as long as pro-Beijing parties managed some % of the vote, they could get seats, diluting the pro-democracy camp, which dominated these races.

Second - The Functional constituencies would see more of its voting come from leaders and bosses than average workers; reversing the 1995 reform. Under the UK reforms, over 1,000,000 workers in different industries could vote for their functional constituencies. Beijing’s changes took that down to under 200,000. This, in practice, would ensure that Beijing-supporting parties controlled the council, as the votes from these would be dominated by the business-minded and hence “keep peace with Beijing” voting blocks.

A good visual of the functional voting and its complexities can be seen here.

In addition to these changes, the 1998 and 2000 elections would see additional members picked by the Election Committee, which was of course dominated by the Beijing parties.

However, following a wave of protests in 2003 over a proposed national security bill, the government made some reforms to quell anger. The bill in question would have strengthened CCP hands in arresting and questioning citizens without due process. the massive protests and marches of 100,000s of people led to the legislation pulled and the Chief executive step down. This was a prime example of the protest and democratic culture that developed in Hong Kong (and that I discussed more in Part 1)

Most critical changes were the increase in Geographic Constituencies and an elimination of appointees from the election committee. Additional reforms later would have the District Elections get to select a few members, which were more pro-Democracy.

From 1998 to 2016, this was how elections broke down for the Legislative Council. D = Pro-Democracy, B = Pro-Beijing, and I = Independent/non-aligned. Thanks to the functional constituencies, the Beijing-oriented parties would always control the legislature.

This green vs red perspective is important for understanding the broad issues in Hong Kong, but it must be stressed each “camp” had several parties within it that varied in their major issues. Business interests wanted to maintain stability while other parties were more pro-CCP. Some pan-democracy parties were more aggressive than others in their approaches. Also at many points these broad issues took backseat to day-to-day issues from the economy to crime.

Btw, if the 2016 results stand out for the 6 “other” parties - don’t worry I’ll get to that.

District Council Elections

After the handover, the local District Council races stood out as the most clear way to gauge voter sentiment. The council elections were straight forward, with voters picking candidates within their council region (see part 1 for map/history).

Through 2011, the Chief Executive would also get to appoint additional members - with the clear aim of stifling pro-democracy voters. That said, with turnout often low in these elections and broader economic concerns driving the agenda, pro-Beijing parties often did very well. The 2003 elections, following the protests of that year, saw the pro-Democracy camp only narrowly get fewer seats.

Since these elections were mainly advisory, with only small and local issues at play, these were not the main fight of democracy activist.

Of course, that was until 2019.

But we will get to that.

This was the election system that governed Hong Kong from 1997 through 2020. So what caused the 2019 landslide, which then led to the major crackdown? Well things really began to turn bad in the early 2010s.

The Final Straws

The conflict between pro-Democracy activists and pro-Beijing business interests seemed to be at a constant state of balance for some time. However, shifting population sentiments AND changes within China led to an inevitable clash that finally set Hong Kong for the stage it is now.

Rise of Xi Jingping

The developments within China are critical for understanding what would happen in Hong Kong. The most critical item was the rise of Xi Jinping as the Premier/Leader of China.

Xi has proven to be a fervent nationalist with little care for freedoms or dissent within the country. Despite his father suffering under Mao, the dictator has taken a similar track. Xi’s tenure has saw increased censorship, reversing a loosening society that was occurring before his Premiership. On the international stage, Xi’s genocide of the Uyghur Muslims in western china saw international condemnation but little action. Xi has also continued to threaten Taiwan, taking a more aggressive posture on the island than has been seen for years.

Xi shows no care for pretending that Hong Kong has rights. This is reflected in the people he surrounds himself with. In 2014, Beijing released a white paper that stated clearly that Hong Kong’s autonomy was a privilege bestowed by Beijing, not a guaranteed right. One passage from the white paper, which can be found here, read…

“One country, two systems” is a holistic concept. The “one country” means that within the PRC, HKSAR [Hong Kong Special administrative region] is an inseparable part and a local administrative region directly under China’s Central People’s Government. As a unitary state, China’s central government has comprehensive jurisdiction over all local administrative regions, including the HKSAR. The high degree of autonomy of HKSAR is not an inherent power, but one that comes solely from the authorization by the central leadership. The high degree of autonomy of the HKSAR is not full autonomy, nor a decentralized power. It is the power to run local affairs as authorized by the central leadership. The high degree of autonomy of HKSAR is subject to the level of the central leadership’s authorization.

The paper was drafted by Jiang Shingong, a member of China’s “New Left.” To best describe these people is a type of red-blown alliance: aka mixes of fascism and communism. This movement had no care for democracy and mixed a distorted form of Marxism with fascism, nationalism, and totalitarianism.

Once Xi was in power, Shingong spent time in Hong Kong, working to cultivate support within the pro-Beijing parties and study the democratic movements in the population. Beijing was already looking for ways to reverse the democratic tide in the province.

Failed Reform & The Umbrella Revolution

Through 2013 and 2014, Hong Kong was in the middle of a major debate over the nature of Chief Executive elections in the province. The push for direct elections of the executive grew; with longtime activists and younger student leaders, namely under the Scholarism group banner, demanded direct elections for the executive.

Scholarism had arisen in 2012 as it organized protests against a government education policy proposal that would have amended school reading/history to match more with the Chinese Government’s teachings. From these protests, the government backed down, and young activist Joshua Wong rose as a young leader in the democracy movement.

In 2014, Democracy activists, aiming to put pressure on Beijing, held an unauthorized referendum, largely via online polling, on the election system they wanted. Over 800,000 people voted on several proposals, all which all offered some form of public getting to vote for the Chief executive. The turnout for the referendum was meant to show Beijing and the Hong Kong legislature that reform was desired. The vote angered Beijing greatly, which denounced it and worked to scrub it from the internet as much as it could.

In the end, on August 31st, 2014, the announcement from Beijing was that direct elections of the executive could happen, but only after candidates were approved by a nominating committee, and the winner being signed off on by the Chinese Government.

This proposal was deemed unacceptable, and it launched a wave of protests, especially among student groups, in Hong Kong. However, these protests went very different from the past. Protests in Hong Kong were often peaceful affairs, but this time the police used tear gas on protestors and blocked off popular protesting sites. Protestors used umbrellas to block tear gas cannisters and shield themselves. As a result, the tool became a symbol of the movement and coined the protests as the Umbrella Movement or Umbrella Resolution.

The harsher police tactics reflecting the growing totalitarian movement in the mainland of China. The Hong Kong government, meanwhile, ruled by pro-Beijing business interests, worked to keep the mainland happy while also trying to balance popular sentiment. The police actions, however, led to greater anger.

A good breakdown of the protests can be seen here.

The protests lasted for almost 80 days, with activists setting up encampments in the city centers. In total, 1.4 million people would take place in the movement at one point or another.

The movement, unfortunately, came to an end with no concessions. The government dug in firm, and the final encampment in the community of Mong Kok was eventually cleared out. The movement was often fractured, with students disagreeing on tactics or concessions within their own ranks, not to mention older activists. Unlike previous protest movements that often led to the government backing down, this time the Government won.

As a result, the proposed electoral reform for the Chief Executive was scrapped. Reformers didn’t want it, and Beijing was happy to cancel it. The 2017 Chief Executive Election was held under the old system. Pro-Beijing candidate Carrie Lam would win the post. We will talk more about her in issue 3.

The Umbrella Revolution was, for a time, viewed as a bitter disappointment to many. This was the first major protest that did not yield concessions. However, the anger did not go away, and shaped politics for the next several years. Activists would also look at the failures of the movement, and work to improve tactics for when the next inevitable call to the streets would occur.

Localists in the 2016 Legislative Elections

The Umbrella movement shook up politics in Hong Kong heading into the 2016 Legislative Elections. A rush of young candidates from the umbrella movement ran for office, with several young 20 year old’s winning posts. Many did not come from the established pro-Democracy camp, but rather from the Localist Movement.

Localism in Hong Kong, broadly, was a movement that pushed much more for Hong Kong self-determination. In contrast to the established pro-Democracy movement, which aimed to keep Hong Kong autonomous while not poking the CCP bear too much, localists favored much more aggressively pushing potential referendums on possible independence - namely after the 50 year period post 1997 expired. This movement clashed directly with Hong Kong’s Basic Law, which stated HK was part of China. The movement was especially popular with younger voters, who saw 20 years of Beijing constantly trying to crack down on different reform efforts. The movement did turn off some voters, however, with nativist sentiments among different parties.

Several localist candidates would see their candidate papers rejected when the election committee added a requirement to affirm they were not advocating for independence. The new forms and disqualifications furthered localist support and sympathy, and were again seen as overreach from Beijing.

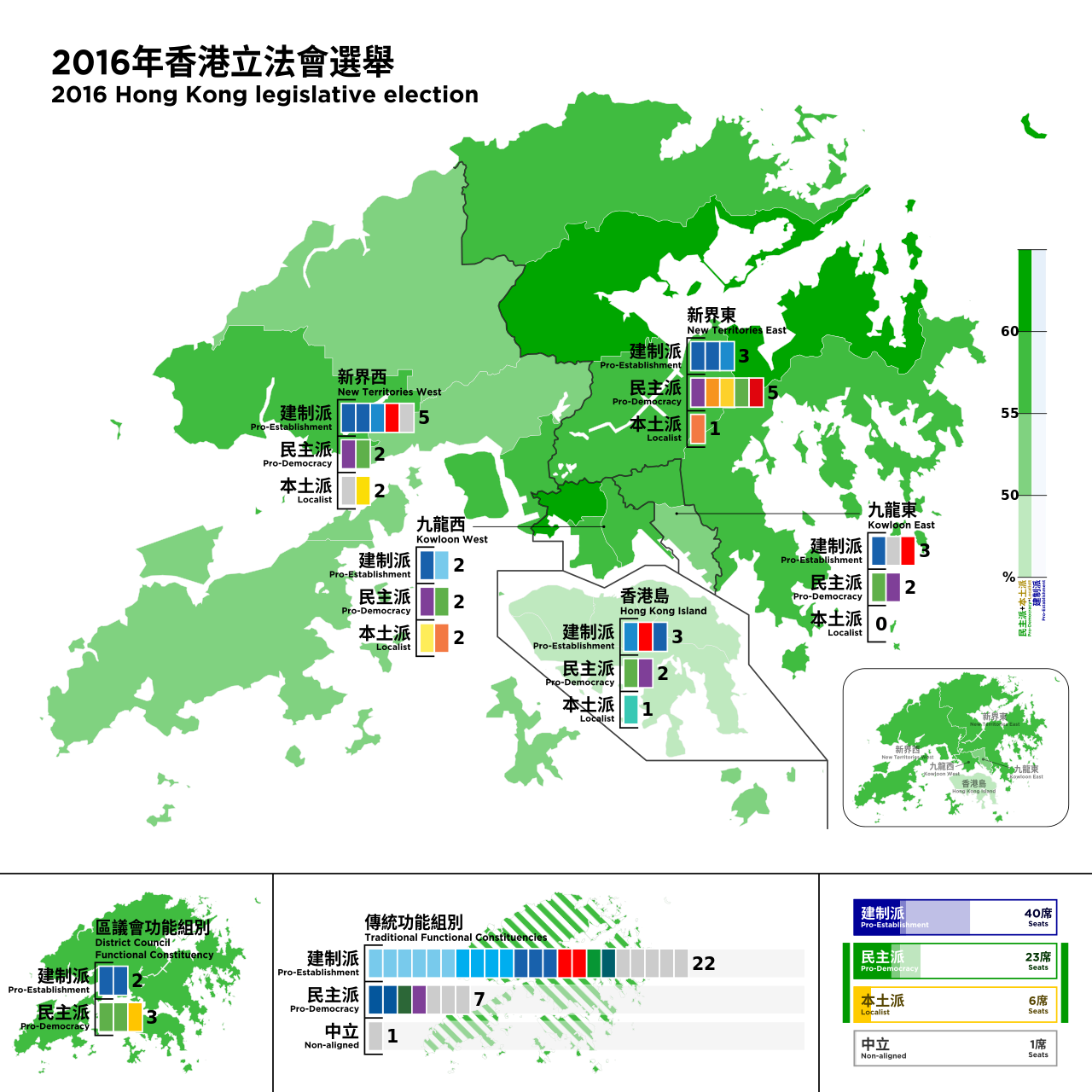

The election results saw the pro-Democracy establishment lose some seats to localists, but combined both forces outpaced pro-Beijing parties in the geographic constituencies. Map below and more details come from here. This map shows the three camps (Beijing, Democracy, Localist) by region.

In the geographic constituencies, the Localist secured 19% of the vote, which almost perfectly matched with pro-Democracy groups dropping 20%, from 56 to 36%. However, thanks to the proportional system, this split did not aid Beijing parties, which actually lost one seat from 2012.

These results did not make Beijing happy, which saw a rising localist sentiment as a continued risk. The functional constituencies would keep pro-Beijing parties in power. Predictably, the functional constituencies gave 0 seats to the localist side.

The Oath Taking Controversy

In October and November of 2016, a major controversy exploded when several localist and Democracy lawmakers were disqualified from the legislative chamber. This move came as several members made alterations to the oath taking, with some members either bringing in pro-Independence props or adding words. In some instances, this included adding pro-independence sentiment, or even directly insulting the mainland.

Beijing directly responded to the controversy, insisting that the Hong King Basic Law barred such independence claims…….

“We will never allow any person, any organization, any political party, at any time, in any way, to split from any part of China’s territory” Premier Xi (source)

First, two lawmakers were rejected before they even formally took their seats, both due to how they took their oaths

Sixtus Leung - Localist member of the Youngspiration Party

Yau Wai-ching - Localist member of the Youngspiration Party

Just a month later four more lawmakers were disqualified for how their oaths were taken

Edward Yiu - A pro-Democracy member from a functional constituency

Lau Siu-lai - A pro-Democracy member of the Hong Kong Labour Party

Leung Kwok-hung - A pro-Democracy member of the League of Social Democrats

Nathan Law - A pro-Democracy member of the Demosistō party

Appeals and challenges went on for years, with non being successful. This unprecedented action continued to set the stage for increasing Beijing crackdowns.

The actions set up further concerns about any hope for Democratic future in Hong Kong, as Time Magazine covered here.

“[The rulings] will confirm their fear that Beijing — while the Chinese Communist Party is in charge — will never give Hong Kong democracy” - Willy Lam of Chinese University of Hong Kong

Challenges in the courts delayed a few of the bye-elections for the seats in question, with four of them, three geographic and one functional, being held in March of 2018.

The March 2018 Special Elections saw pro-Democracy advocates only take two of the four posts; a bitter disappointment for the pro-democracy side. Turnout within the districts was down, just 43%; with many attributing it to disillusionment about the over-reach from Beijing.

“They have concluded that any candidate who shares that dream, as they define it, will be [disqualified] either as a candidate or afterward, as a Legislative Councilor. So they must feel not indifference but a sense of futility and defeat,” - Writer Suzanne Pepper

For pro-Beijing forces, the entire oath taking saga was a victory. The opposition was frustrated and demoralized; unsure how to proceed.

But Then…..

It seemed the pro-Democracy camp was stuck between a rock and a hard place in the fight against Beijing rule. The public was demoralized and apathy was at risk of setting in.

But then, in 2019, the Hong Kong Government began to debate an extradition law. A law that could open up Hong Kong residents to the whims of the Chinese legal system. That proposal was the last straw. The debate over the law would spark a massive protest movement, lead to a massive electoral swing, and hence lead to the final brutal crackdown from Beijing.

I will cover that on Monday in Part 3.