Issue #143: Hong Kong's Democracy: Part 1 - The Rise of Civic Action

The 2019 Elections Led to a Beijing crackdown

(This is Part 1 of a 3 part series on Democracy in Hong Kong. Expect Part 2 in the next few days)

On December 10th, voters in Hong Kong went to the polls to elect members to their local councils. The elections came four years after the 2019 local elections, which saw parties aligned with the province’s pro-democracy movement crush pro-Beijing parties.

The elections marked a dramatic turning point in Hong Kong politics. The victory for parties that broadly pushed back on control from Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party.

The results were a victory for Democracy - and would become the final straw for Beijing - leading to massive crackdown that today leaves “elections” in the area a complete farce.

This newsletter will aim to summarize a complex legacy of Democracy in Hong Kong, the drive for more freedoms, and the recent crackdowns by the Chinese Government.

For more on Hong Kong’s democratic history, I highly recommend “Among the Braves” by Shibani Mahtani & Timothy McLaughlin. Go buy it now.

I cannot stress how much this book helped me understand and frame the Hong Kong saga. My research included countless articles, videos, and Wikipedia election pages, to try and summarize a complex story into something fairly concise. The book aided me in many details and delves deep into important activists and civil leaders who fought for Democratic rights. I cannot do those people justice here and I cannot recommend this book enough. It will keep you reading through the night. It puts a human face on a tragedy that is often seen as cold and statistical.

With all that, lets dive in.

Hong Kong’s History & Democratic Drive

To Understand the situation in Hong Kong, we must understand the history that set it apart from the rest of the mainland.

Spoiler, like most conflicts over borders today, it starts with a European power.

The British Empire Comes Knocking

Hong Kong is likely best known to westerners as the province of China that is “technically” China but is very autonomous - and where capitalism and some democracy are practiced. This comes from its history as a British protectorate that was established after the Opium Wars; which saw the British empire work to create a trade imbalance with China by getting their population addicted to opium. The resulting war was a humiliating defeat for China and the treaty set up several trading posts, including Hong Kong, for the British.

A concise summary of that war, under 5 minutes, is here.

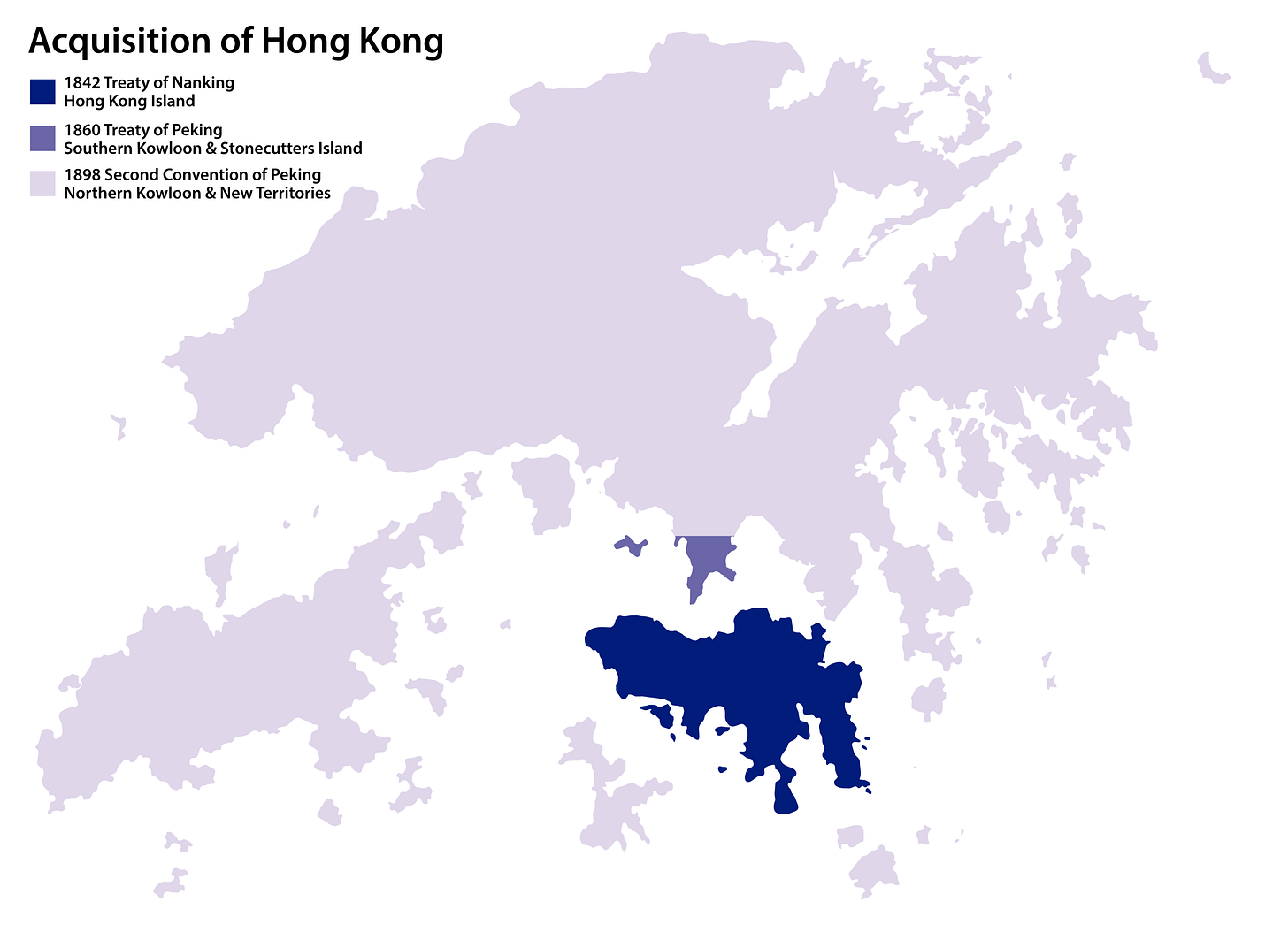

The initial treaty in 1848 gave Hong Kong Island to the British, but later in 1898, the British acquired a lease on the surrounding land that now makes up the broad province of Hong Kong. Map source here.

A good detailed history of early Hong Kong rule under the British can be seen here.

Hong Kong would develop very different from the Chinese mainland, especially following the Chinese Civil War and rise of Mao and Communism. Hong Kong also became a major refugee site for people fleeing Mao’s rule. The Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution saw hundreds of thousands flee the mainland to make it to Hong Kong. Many future Democracy leaders descended from these refugees, who carried stories of harsh CCP rule. From 1951 to 1961 alone, the population of Hong Kong went from 2 to 3 million people.

When China became isolated following the communist victory, the location of Hong Kong, coupled with its British rule, made it an appealing site for businesses. The province was directly ruled by the British, which meant businesses saw it as a stable place to set up shop. The once poor province saw major companies come in and thrive. Of course, this left a population divided between a rising middle/upper class, and abject poverty. The contrast of vast apartment buildings not far from slums and shacks was a common sight in the region. However, while Hong Kong would become known for business tycoons, the presence of the companies did increase the middle class of the province.

However, Hong Kong would not remain in the hands of the British forever. A treaty in 1898 gave the British control of the region for 99 years. The diplomates at the time viewed this “as good as forever” - however, that would not be the case.

Politics of the British Handover

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was clear that a handover of Hong Kong to China would happen. The Chinese Government had emerged out of isolation, taken Taiwan’s place in the UN, and begun to flex its muscle. With decolonization the major driver of the day, the UK was not in a strong position to hold onto the islands.

Even in the 1970s, before a handover was locked in, the British administration in Hong Kong worked to improve economic conditions in the island, as well as begin a process of democratization. At the bare minimum, the Government of the UK did not want China to be seen as a benevolent force that would be able to easily absorb the province. Reducing poverty and housing issues was a major driver; as fewer in poverty means fewer willing to risk major change. While the British had their own selfish reasons for seeking to drive up the differences between Hong Kong and the mainland, it was beneficial for its people.

In the 1980s, British Prime Minster Margaret Thatcher met with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping about the handover. Despite surveys indicating over 80% of the population wanted to remain under British rule, the option to not turn over Hong Kong was not in the cards. Deng made it clear to Thatcher that the country could easily take the province by force; and that they would do so to erase the “shame” of the Opium Wars. While the initial treaty for Hong Kong island did not have an expiration date, China made it clear the ENTIRE province had to be returned. As discussed here, it was clear China would invade Hong Kong if a deal was not reached.

"I could walk in and take the whole lot this afternoon" (Deng to Thatcher)

Thatcher knew a war could not happen, with international condemnation and sanctions being the only real threat the West would be willing to offer. For China, taking back Hong Kong had to happen for the sake of history, but they likewise did not want to isolate themselves again.

After tense negotiations over many years, the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration was announced. It created the notion of “One Country, Two Systems.” For the next 50 years after 1997, the freedoms and rights of Hong Kong would remain largely untouched, with emerging democratic reforms safeguarded as well. However, the clause and emerging details would give China continued avenues to get involved in Hong Kong affairs. This, to some degree, the announcement eased the minds of Hong Kong residents that feared a crackdown the second 1997 came. Others were not so sure and expressed great frustration at the handover plan.

Thatcher believed and hoped China would remain dependent on Western support; and hence would be forced to leave Hong Kong alone.

She was wrong.

Civic Engagement

Regardless of the decisions being made between leaders and diplomates, the population of Hong Kong was already instilled with a democratic drive. The emergence of local elections in the region (more on that in next section) and the contrast of the region’s free press from the stories of censorship on the mainland led to Hong Kong residents developing a strong distrust of the Beijing Government. This hit a fever pitch in 1989 with the Tiananmen Square protests - led by students in the mainland. The protests were warmly received in Hong Kong, with residents holding protests in support.

Protests in Hong Kong at the time were family affairs, with people largely peacefully marching to show their solidarity. Crowds chanted opposition to Chinese Premier Li Peng. The slogan went

“Li Peng, Li Peng, we will not accept your tyranny”

Another fun note, actor Jackie Chan was also in the crowds.

Residents formed The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China - one of several organizations to come that pushed the principles of democratic rights. Among the crowds were future Democracy leaders. Martin Lee, often called the “Father of Democracy” for Hong Kong, was expelled from the committee working on the details of the British handover after he angry denounced the Beijing government when the crackdown on the Tiananmen protests began..

The eventually crackdown on the mainland protests, which saw the Government run tanks over students and fire with guns, led to a massive wave of grief in Hong Kong. Democracy leaders in the island had traveled to the protests, and many residents saw their democratic future at grave risk if the government was willing to violently crush protestors the way it did. Residents flocked to march and protest on July 4th, 1989, and the date has become a yearly anniversary. Residents would flock every July 4th to Victoria Park and hold a vigil for those killed and arrested in the attack.

And the image of the infamous “Tank man” - an unknown civilian standing in the way of tanks during the crackdown, became an international collective memory.

On top of protesting the actions, Hong Kong became a safe haven for activists on the run from the Beijing Government. While Western leaders did little but condemn the massacre, they worked behind the scenes to aid wanted activists/leader in getting to other nations. Hong Kong became a major halfway house for those who fled the mainland and then needed to get to other countries. Citizens from all walks of life; from religious leaders, students, professors, labors, worked to aid people in staying low while in Hong Kong as they awaited a flight out. The Hong Kong mob (known as the Triads) even used their smuggling efforts to aid people in escaping the mainland.

From Hong Kong, many civic leaders and activists from the Tiananmen protests made their way to Europe and North America. The massacre and its aftermath would affirm a pro-Democracy sentiment within the province, especially among the working class.

Protests and push-backs against what the voters saw as “over-stepping” by Beijing would continue through the years. The election systems in Hong Kong (which will be described below) would ensure all leaders of the island would lean toward Beijing on issues. In 2003, an effort by the ruling government to introduce a law that would allow for arrests and questioning without probably cause, something common on the mainland, led to a wave of protests and an eventual shelving of the law.

For the next decade and a half, a cycle of over-reach by the Government followed by protests, and sometimes backpaddling, would take place.

But why was the Government constantly at conflict with the people? Well lets look at how elections began and evolved in Hong Kong.

Early Democratic Reforms

For much of British rule of Hong Kong, elections were very limited. The province was largely ruled by the royal Governor, who was selected by the British Government. Since the late 1800s, small elections for municipal boards were held. These boards were largely advisory but served as a way to gauge concerns. That said, suffrage was limited based on careers and positions in society. Voter rolls from those offices normally topped around 40,000 and only saw 10,000 votes on average cast. To highlight this, here are a few of the urban/municipal elections, with population and voting figures compared.

Democratic reform really began at the start of the 1980s. This tied with the looming deadline for a hand-over of Hong Kong to the Chinese Government. Seeking to booster Hong Kong autonomy before the handover, election reform began to pick up steam.

The first major change was the set up of elections to District Councils. While similar to the earlier councils from the late 1800s, these were more formally organized and had broader electorates. Many seats on the councils were appointed, but the 1982 election saw 132/490 seats decided by voters. The election saw over 340,000 ballots cast with the registered roll at 900,000. This was the first true democratic race in Hong Kong.

The region was divided into these 18 districts, with each be ruled by a council. The process continues today. Map source here.

Just months before the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, the UK published the Green Paper: the Further Development of Representative Government in Hong Kong; a series of electoral reforms. The proposals established INDIRECT elections for the to-be-established Hong Kong Legislative Council. The paper would set up new elections in 1985 for the District Councils, which would have the total number directly elected expanded. At the same time, elections for the Legislative Council would take place. The way these members were decided was multi-tiered

Voters from certain sectors of the economy, as well as companies themselves, would be able to elect members via Functional Constituencies. A breakdown of these can be found here.

Additional seats would be part of “official members” - essentially permanent positions, like cabinet members, always having seats.

Appointees from the Governor

Appointees from an “electoral college” made up of urban/municipal councils. This included the District Councils with more direct elections.

The Green Paper also set up an Executive Council headed by the appointed Governor and with members coming from the Legislative Council and other appointees. The reform also aimed for the Governor to slowly yield less power and allow the new systems to govern. The reform was meant to be a first step in Democratic reform, with the Green Paper pledging to considered more direct elections via geographic constituencies down the lines.

For those having trouble keeping track (can’t blame you) - this was the Hong Kong structure post 1984.

The province was still largely ruled by appointees and limited franchise elections (largely functional constituencies) - but the first bit of true democracy was introduced.

Democratic Expansion

Following the 1985 elections, the UK administration continued to move Hong Kong in a more Democratic direction. In 1987, it introduced the Green Paper: Review of Developments in Representative Government; another proposal of reforms. The most notable was consideration for the DIRECT election of the Hong Kong Legislative Council.

The reform proposal came at a time when the British and Chinese Government were working on their “Basic Law” - which would govern the province post its handover - essentially its constitution. Chinese officials objected to the direct elections, arguing they were create instability in the island (and of course contradict to much with China’s 1-party state).

Business groups and many unions also did not want their Functional Constituencies weakened. With Hong Kong in an economic boom, the opposition argued that direct elections could lead to political uncertainty that could hurt its attraction of businesses. Voter sentiment leaned in favor of the reforms but was not overwhelming, with poverty reductions still the biggest concerns.

As a result, the Government opted to go for slower reform. The 1988 Legislative elections would continue under the old system. In 1991, however, 18 members would be elected directly by voters in geographic constituencies to the legislature. The layout for the election would be as followed

Hong Kong would be divided into 9 Geographic constituencies

Voters would elect two members in the constituencies they lived, bringing to the total to 18

Another 21 members would come from the Functional Constituencies

An additional 21 members would be appointed or be individuals like the Governor or other administrators

With this, the legislature would take on some, but not all, of the democratic elements seen in the local council races.

The 1991 election was heavily shaped by the Tiananmen Square massacre, which caused great unease within Hong Kong. As a result, all 18 members directly elected came from pro-Democracy camps, with candidates backing Beijing interests securing none. The “United Democrats” (Green), led by Democracy leader Martin Lee, dominated the election

This map and a much deeper-dive into the 1991 Elections can be found here. The domination of the pro-Democracy parties stunned many observers, who believed that the 2-seat system would elect some more conservative and Beijing-minded members. I should note, but I will delve into this more further down. The “Pro-Beijing” side broadly refers to a mix of folks who did not want a radical break from China and were largely tied with business interests.

These elections and Tiananmen Square led to the Electoral Reforms of 1994, which caused a great deal more tensions with the Chinese Government.

The 1994 Democratic Reforms

The stage was set in the early 1990s for a greater rate of Democratic reform. The crushing of the student protests in Tiananmen Square cause the UK Government to seek a quicker democratization of the region. The first clear step was UK Prime Minster John Major replacing David Wilson as the ruling Governor. Wilson had taken a more moderate stance on democratic advancement, seeking to not anger the Chinese Government. He was replaced with Chris Patten, who’d been involved in electoral politics and was considered much more pro-Democracy.

Patten had limits to what he could push. The Basic Law, which was going to be the region’s mini-constitution that was worked out between the British and UK Governments, locked in that many seats in the Legislature would be via Functional Constituencies. Patten instead came up with a serious of reforms to expand Democracy as much as possible within the limits he had. Some of the major reforms included….

Establishing Single-member districts within the geographic constituencies

Lowing voting age from 21 to 18

Abolishing appointed members of District Councils

In some Functional Constituencies, move it so more workers could cast ballots and not just the corporate leaders/bosses.

Expansion of Functional Constituencies to include more potential voters by bringing in more industries.

The proposals were met with considerable hostility from the Chinese Government. Patten was painted as the face of the reform and portrayed as someone sabotaging the handover and dividing the province. Business interests rejected the plans, again sticking to a “less change the better” mantra. Conservative British politicians also did not like the proposals, seeing them as hurting relations with China. In the end, many did not consider Hong Kong’s democratic rights to be worth angering the CCP. Regardless, with John Major’s Support, Patten moved ahead. A slightly amended proposal would pass the Hong Kong legislature and be used for the 1995 elections.

The 1995 Legislative elections would again be a resounding win for the pro-Democracy parties. A deeper dive is here, but the general breakdown was

From the Geographic Constituencies

16 Seats for Pro-Democracy parties

3 Seats for Beijing-Aligned parties

1 Seat for independents

From the Functional constituencies

10 Seats for Pro-Democracy Parties

16 Seats for the Beijing-aligned parties

4 Seats for independents

10 appointees

In total, the pro-democracy side outpaced the pro-Beijing side 29-24, with 7 non-aligned. The legislature would pick a moderate leader and hope for a smooth handover in 1997.

This election was critical in setting up the polarized politics that Hong Kong would endure for the next two decades. Many parties would form and run, but broadly they would fall into two camps.

Pro-Democracy: These more liberal organizations that sought greater Democratic rights, pushed back on Beijing interference in local affairs, and some ultimately wanting full independence. For much of their existence their main issues were expanding voting access and keeping Beijing at bay.

Pro-Beijing: Heavily dominated by business interests and conservatives. These parties saw cooperation with Beijing as good for economic growth and worried that too much tension would lead to crackdowns and instability.

This dynamic would outlive the 1994 reforms.

As a result of the elections, Beijing terminated the ”through-train arrangement" - which would have allowed the elected legislature to continue to serve after the 1997 handover. As a result, Beijing held elections in 1996 for the “Provisional legislature.” This election, held on the mainland and more of a “selection” saw a legislature of 54 pro-Beijing members and just 4 steadfast pro-democracy members.

This provisional legislature would rule the province once the handover took place in 1997, with the body then seeking to re-amend election systems before new ballots were cast in 1998.

Looking Ahead

With the handover looming and Beijing promising to make changes to how elections were run, the mid 1990s was tense for Hong Kong. How China would handle the handover and its subsequent administration of the region will be discussed in Part 2.