Special Issue: On this Day in 1845 - Florida's First State Elections

First statehood votes after 20 years as a territory

(Note: This issue was originally published in 2023. I am re-sharing it now to commemorate the anniversary of Florida’s first statewide elections)

Today marks the anniversary of Florida’s First State Elections - which took place on May 26th, 1845. These elections, held for Governor, legislature, and Congress, came just months after Florida finally achieved statehood.

In honor of this, I want to share an article I wrote in 2020 looking at these contests in great detail. I will also offer a rapid-fire summary of events here, but I definitely recommend the full article for a more in-depth picture.

Florida’s First Elections Article

With that, lets take a trip down memory lane.

Territory elections

Before Florida became a state, it was established as a territory in 1822. At first the President appointed both a Governor and territorial legislature. Legislative elections would begin a few years later, however. The territory had the option to appoint a non-voting Delegate to Congress or hold elections for that as well.

I covered the early territorial political situation in this article - which covers first elections for delegate. The state’s early politics was heavily driven by West v East Florida sentiment. Pensacola and St Augustine were competing for influence in the early territory and the population centers were world’s apart. Tallahassee’s establishment as the State Capital was to be a middle point. Otherwise trips from the two major cities could take weeks.

Early Florida politics was also dominant by loyalists to Andrew Jackson. In 1822, it seemed Richard Keith Call and James Bronaugh, both Jackson men, would battle it out for the Territorial Delegate spot. However, after Yellow Fever broke out in Pensacola in 1822, the election was postponed. Joseph Hernandez, an East-Floridian, was appointed to the delegate post by the west-dominated council as a sign of cross-region appeasement. Bronaugh then died of Yellow Fever, clearing Call’s path to be the designated Jackson man in upcoming elections.

Elections were finally held in 1823 for delegate. Thanks to unanimous support from the West, Call won the contest.

You can read far more about this contest in my Yellow Fever and the First Delegate Election article. I wrote it in early 2020, just as COVID began to take over our society.

Call would only serve one term as delegate, but would remain an important figure in territorial Florida - serving as appointed Governor as well. Elections for Territory Delegate would often be regional affairs with less focus on any sort of party loyalties.

I intend to delve deep into all the territories’ politics, from delegate elections to the territorial legislature, in the future.

Path to Statehood

Calls for statehood began to grow in earnest in the mid 1830s. In 1837, Richard Keith Call, now an appointed Governor, set up a referendum asking if statehood should be pursued by the territory. The measure passed with strong support from the Middle Florida counties - which made up the planter class establishment of the state.

East Florida was eager to break into its own state and saw statehood as a threat to that effort. West Florida was likewise warry of the growing power of middle Florida - which was known as “The Nucleus” in political circles.

Delegates gathered at Port St Joe to work on a constitution. This time is credited as when party politics and factions really flourished in the state. The delegation met amid the Financial Panic of 1837 - and as such the delegates were in a strong anti-bank and anti-finance mood. These were largely rural democrats, while Whig-style upper-class plantation planters and merchants favored a stronger financial system. Yes this all sounds like Hamilton vs Jefferson or Jackson vs Clay.

A conservative and anti-bank constitution was drafted and sent before the voters. The measure narrowly passed in 1939.

Florida drafted a slave state constitution - which laid out that the legislature could never repeal slavery and expressed the right to ban freed black people from the state’s borders.

Congress moved slow on Florida however. Many Northern politicians despised the Florida’s rigged constitution. In the meantime, statehood got a boost when David Levy was elected as delegate to congress. Levy, a slavery Democrat, was a firm statehood pusher.

Levy, who emerged around the time of the convention, became one of the prominent Democratic Party leaders in the state. Meanwhile, in 1841, Call was again appointed Governor (he’d been removed shortly after statehood referendum). Call would be the de-factor leader of the emerging Whig Party in the state.

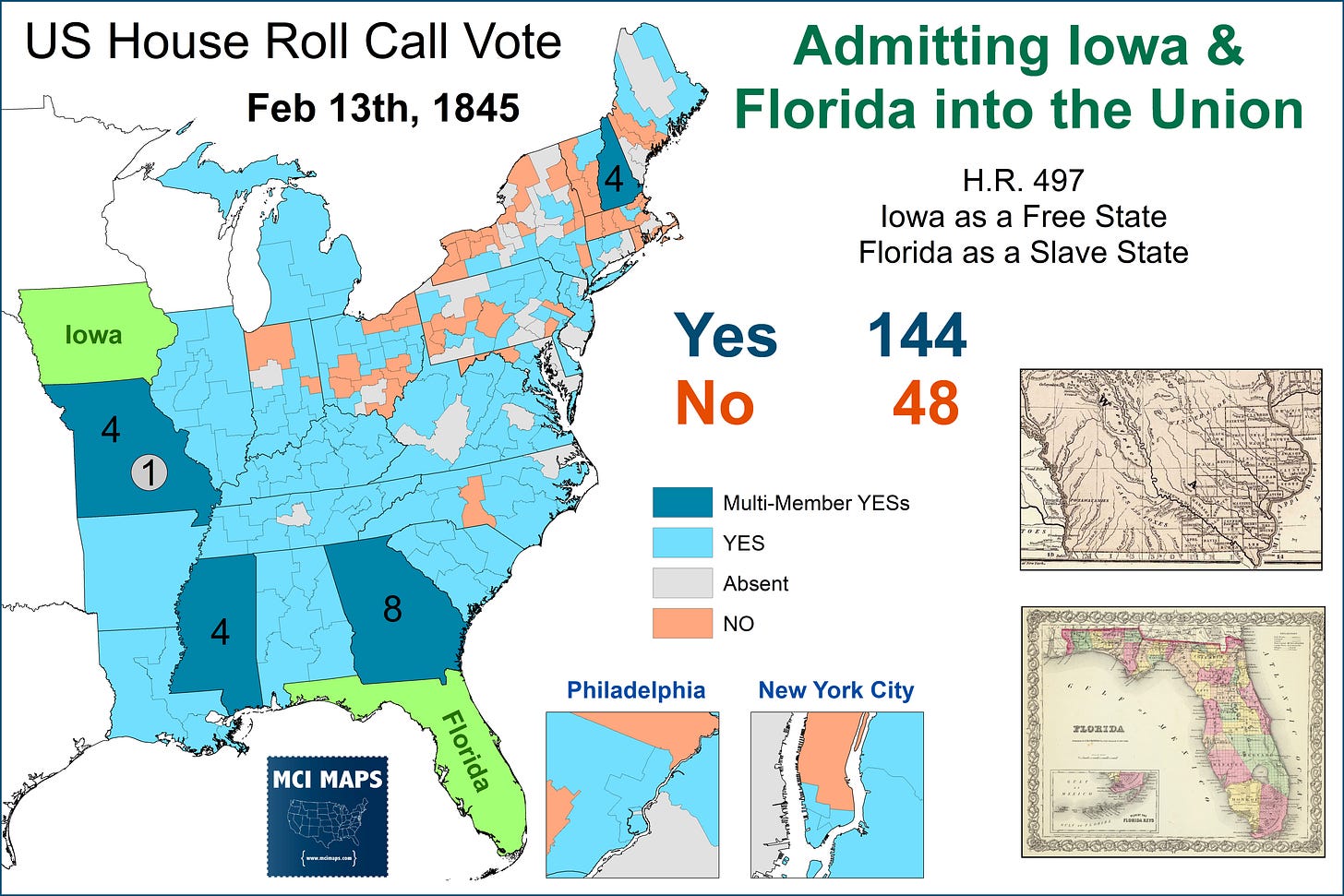

The final statehood push took place in 1845. There Florida and Iowa were to be admitted to the union together; with Iowa as a free state. First, an attempt was made to allow for East Florida to break off and become its own state. This provision was originally added to the bill. It was backed by Levy, who hailed from East Florida, and slavery backers. Both Florida’s would almost surely be slave states. A vote to remove the provision passed on purely sectional lines.

After this, and after efforts by Northern congressmen to change Florida’s constitution, statehood would pass - largely only failing with anti-slavery Northern Congressmen.

The Senate would soon follow suit and Statehood was achieved on March 3rd, 1845.

This set up elections for the new state for May.

Statewide Elections

Heading into 1845, it was clear Florida would have a democratic edge over the Whigs. Democrats were popular with the rural poor while the Whigs represented the upper and middle classes. The state’s demos pointed to a more natural gravitation toward Democrats. Both parties would hold conventions to pick nominees.

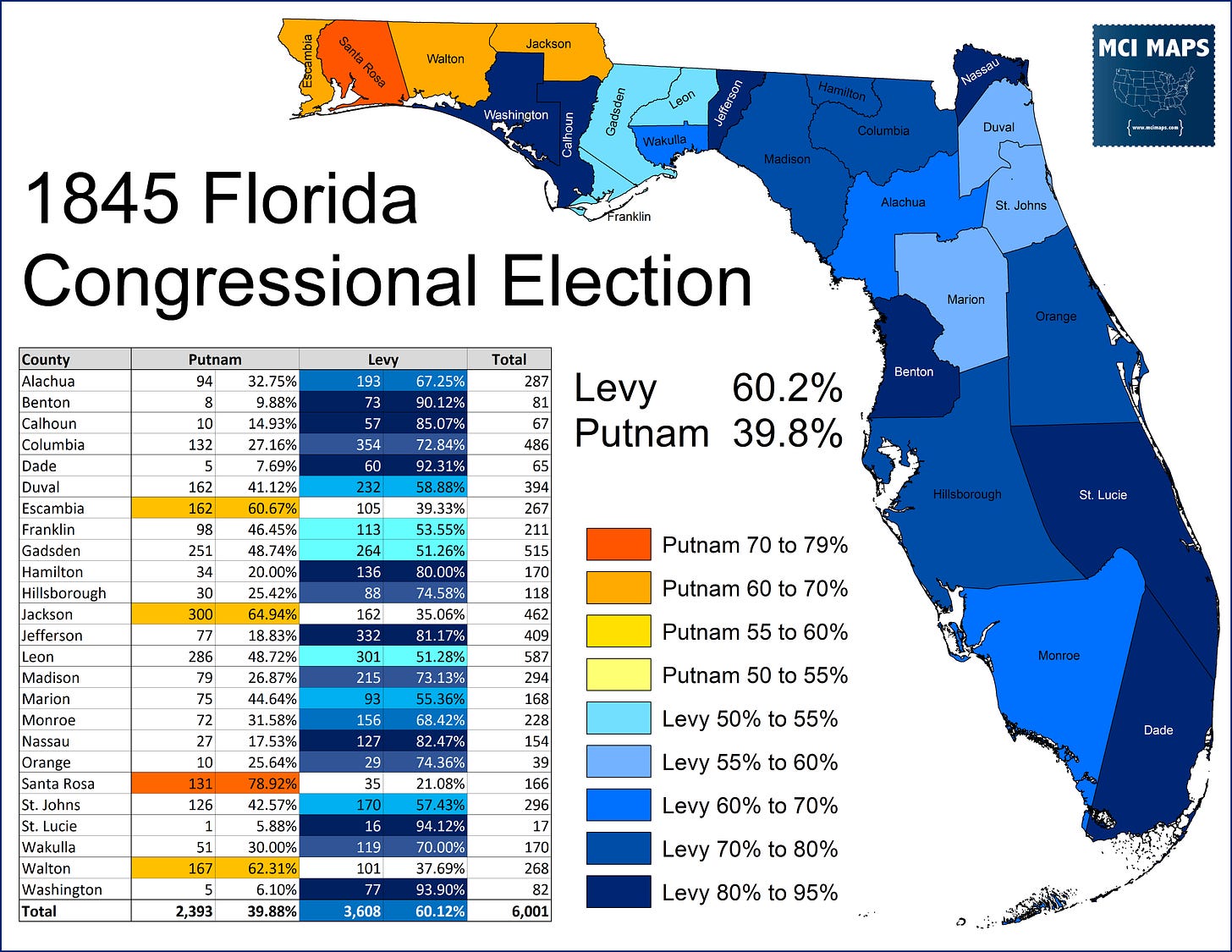

David Levy opted to run for the state’s lone Congressional Seat. He made it clear, however, that he wanted to be appointed Senator if the legislature elected was Democratic. For Governor, the Democrats nominated William Moseley, an active but far less high profile territorial politician. The move was an effort by Levy to be the main campaigner and leader of the Democratic faction.

Whigs were far less organized, and struggled to even set up a single state convention. Their first pick to be Governor, William Bailey, rejected the nomination. On top of that, the east and west counties were split over who should be the Congressional nominee. In the end, they convinced Richard Keith Call to accept their nomination. Since Call represented Tallahassee, the party agreed to Benjamin Putnam, of St Johns, to be the Congressional nominee. This at least gave some regional balance.

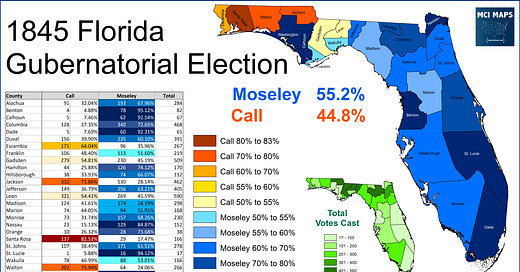

The lack of Whig organization foretold the election results. Democrats easily won the elections. For Governor, Moseley won with 55% of the vote.

Call’s 45% was a high water mark for the Whigs that day. In the Congressional race, Levy won 60%, taking Leon County from the Whigs.

Precinct data from some counties are available. The data from Leon County shows Levy outperforming Moseley across the area, even flipping a Call precinct.

I also go into some Nassau county precinct data in my in-depth article.

The legislative races were big Democratic wins too. In the State House, Democrats won 30 seats to the Whig 11.

In the Senate, the margin was 12 votes to 5.

This would eventually lead to David Levy becoming Senator for the state. Democrats would be the biggest party in the state from here and through the civil war.

There would be Whig Victories however. In fact, the special election for Levy’s seat, held in October of that same year, would see a race so close that it took Congress deciding on a winner. It would also be a catalyst to Whig’s getting a brief bounce in the state.

To read about that, however, you gotta give my much more in-depth look a review.

As always, great work by Matt Isbell.

Great stuff here Matt and tracks with the period of time, the territorial days that I’ve been studying recently so I appreciate this post gives me even more to chew on.