Issue #72: Cuba's Historic Family Code Referendum

A referendum without government rigging?

On September 25th, voters in Cuba went to the polls to cast ballots for a referendum on their family code. The referendum, among other things, legalized same-sex marriage in the communist state. The vote was history for its broad support, but also the fact the referendum happened at all. Anyone who knows anything about Cuba knows that is has been under communist rule since 1959. The nation does have elections, but these are not free. The referendum last month was notable for being the most open election in modern Cuba.

For this substack, I wanted to dig into the Cuba family code referendum and its historic significance.

Cuba’s Fake Democracy

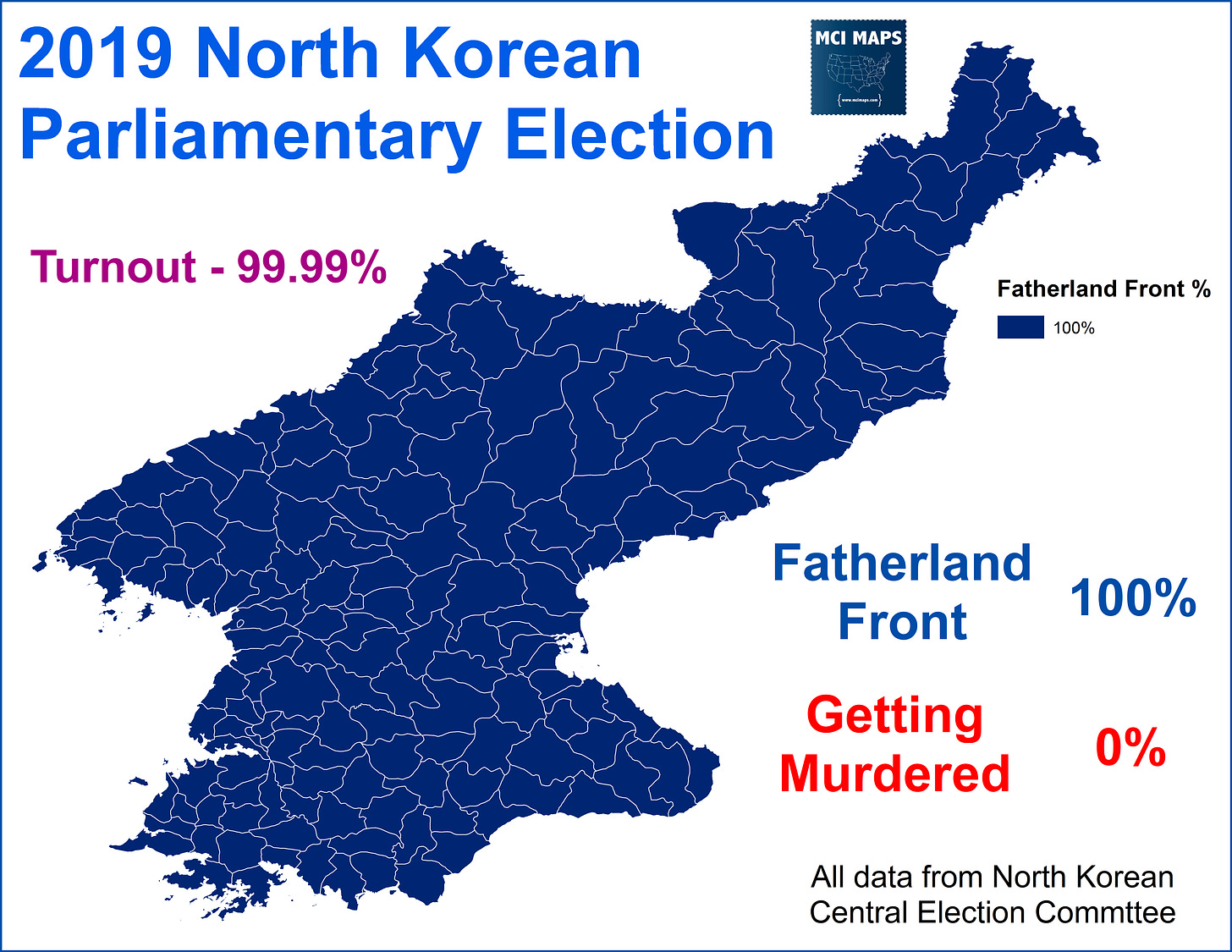

As stated, Cuba does have elections. These votes have often been for local councils or parliament. However, these races are not free nor fair. The Cuban election system is similar to those employed in other authoritarian governments. For example, this is a map of the 2019 North Korean elections. No joke, they had “elections.”

Just last year, Syria held elections; which saw Assad easily win another term via a totally fair vote.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, the 2018 parliament election did not allow opposition parties to run; giving the communists and their allies 100% of the seats.

In 2019, the country held a referendum on its new constitution. The results were 90% support with 90% turnout. All provinces gave 84%+ Support.

Those figures themselves should make you question how fair they were, but beside that, their were ample examples of ballot rigging and pressure during the vote.

Cuba has used elections to claim legitimacy. However, democracy activists on the island have continued to clash with the communist regime; with stifles dissent on most matters.

The 2019 constitutional referendum, which clearly was subject to some rigging/pressure, did remove the same sex marriage ban. However, a full implementation of legalized same-sex marriage (or any other marriage rules) would need to be approved through the nations family code law.

The Family Code Vote

By many accounts, the family code vote actually was held under true democratic principles. The debate over the topic began around 2018, as LGBT activists began a social campaign to change the state’s ban on same-sex marriage. This took place as the 2019 Constitutional drafting/referendum was underway. LGBT activists had a strong ally in Mariela Castro, the niece of Fidel Castro and daughter of Raúl Castro. The push for ending the ban led to a counter-campaign from several Evangelical Christian churches announced their opposition. However, while 60% of Cuba is identified as Christian, the data is more complicated thanks to the nation’s history.

Cuba, like many Caribbean islands, was heavily Christian, and specifically Catholic, before the 1959 Communist Revolution. After the rise of Fidel Castro, the church was severely repressed in the nation. Over 80% of clergy left the island and Christians were barred from Communist party ranks. Large churches were closed and worship went underground for those who continued to practice. It wasn’t until the 1990s and the fall of the USSR that the communist party pushed a reconciliation with the church. The 1990s reforms; which saw laws to outlaw religious discrimination and an opening of the communist ranks to believers. These reforms culminated in 1998 with a visit from Pope John Paul II.

Today, people can practice the major faiths with little issue; through the Church is still subject to surveillance and scrutiny. The effects of this history, however, means that while many Cuban’s might identify as Christian, they also do not consider themselves very religious. A 2015 study found 44% of Cuban voters did not consider themselves religious. The article points out the complicated nature of quantifying religion in Cuba. There is a clearly many who when pressed would offer a passive identity with the Christian Church, but also do not consider themselves major practitioners.

In the time leading up to the 2022 vote, the government spent months working in local meetings with communities leaders to work on crafting what would ultimately be a 100-page document. The new code made many changes to the nations’ 1970s-era family rules. Some changes were…

Legalization of same-sex unions

Allows same-sex couples to adopt

Allows surrogate pregnancy

Increasing rights of children from parental neglect

Increases rights of the elderly

Equal rights between men and women

Many Evangelical Churches led the opposition campaign; while the Government urged a Yes vote. The campaign saw open debate between both signs, with opponents and supporters printing signs and posters advocating YES or NO votes. This level of open democratic debate is rare in Cuba. While dissent against the communist state is heavily repressed, dissent from this vote was tolerated.

The election was held on September 25. Few reports emerged of the type of intimidation that has dogged past campaigns. In the end, the island backed the family code with 67% of the vote. Every province on the island gave its support.

Turnout for the referendum was 74%, which is notably lower than the “elections” for parliament or the constitutional vote. This is thanks to not only no pressure DEMAND to show up, but no fudging of numbers by the election authority.

The fact the referendum would not feature compulsory voting was something gay rights activists actually had to factor in with their campaigns. Some activists for democracy had considered pushing to boycott the vote as a way to registered displeasure with the regime. This left backers of the reforms working to argue such a protest act would only hurt others by causing a possible defeat of the measure.

The success of the referendum is not only a victory for LGBT people in Cuba, but also an important true democratic step for the island. No this does not mean we should expect the next parliament votes to be free/fair. However, this is undoubtedly a vote that will go down in history as being an important first step.

American Cuban Voters and LGBT Rights

We saw the emerging Christian church in Cuba be a major opponent of the family code referendum. Likely one of the things that helped the YES campaign was that while the island is passively majority Christian, the organized church is still much less powerful than it is in America. This is tied to the history of religion in Cuban I discussed.

Meanwhile, in America, Cuban exiles and their descendants have been long able to attend churches and develop their own views. A vast majority of Cuban voters, who’s history in Miami-Dade politics I covered here, are Christian. Right around 50% of Cuban voters in 2013 identified as Catholic. As a result of this religious makeup and allegiance with the GOP, Cuban voters are socially and economically conservative. This stood out in 2014 when the Cuban regions a rejected medical marijuana referendum. In addition, the Cuban community voted to ban same-sex marriage in 2008.

I delve deep into this vote in my substack post here. The measure to ban same-sex marriage easily passed in 2008 with white and non-white support. This referendum map would look very different today; as it predates the shifting views among white and non-white Americans. Today an estimated 70% of Americans support same-sex marriage. Back in 2008, that nationwide support was well under 50% and non-white voters, who are heavily religious, were steadfast opposed.

The map below shows the ban results in census tracts that were 50% Cuban or more. While 62% of the state banned same-sex marriage, the ban got 69% in the Cuban-majority areas.

You got to love the little Florida International University island in the middle.

Now, this vote was 14 years ago. I would venture gay marriage would have failed on the island back then as well. That said, I would not expect a modern same-sex marriage referendum to get 67% of the vote in these precincts either. The island’s population is likely much more accepting of same-sex marriage; with this being a reflection of its religious history and the effect on the Church’s strength.

Other National Referendums on Gay Marriage

Cuba is not the first nation to hold referendums on same-sex marriage. There is a long history of national votes in different regions on the world. I’ve delved into two of these referendums in the past: Australia and Ireland.

In 2017, Australia held a non-binding referendum on same-sex marriage. The vote saw 62% of voters back equality; with all states voting for it.

In the Australia vote, the most prominent opposition regions were inland Queensland and western Sydney. The inland Queensland area is a very conservative region. Western Syndey is home to a large number of working-class immigrants from the Middle East and Asia. The region is also the home of choice for religious suburbanites. Overall, due to high Christian and Islam shares of the population, the region has been referred to as the Bible Belt of Australia.

Australia’s parliament would formally legalize same-sex marriage after this referendum,

In 2015, Ireland held a referendum to legalize same-sex marriage. This referendum was historic, as it made Ireland the first nation to legalize same-sex marriage via a popular vote. I wrote about the 2015 campaign in this post.

The referendum lost in only won rural riding; while absolutely dominating in the Dublin area. The vote was especially historic considering Ireland’s long history of social conservativism and influence from the Catholic church (which I talk more about in the article).

Conclusion

The vote in Cuba is historic for island, marking one of its first fair elections in the modern era. It also ads Cuba to a long list of nations approving LGBT rights via popular vote; something unthinkable just two decades ago. However, the nation still remains under a one-party state where free expression isn’t a guaranteed right. The positives of the referendum should not be used to excuse other repressive actions; or be used to claim Cuba is a real democracy. The island still has a long way to go on the democratic front; something many activists are risking their lives to push for.