Issue #70: Kenya's 2022 Presidential Election and avoiding Ethnic Violence

Kenya had ethnic clashes in 2007, so it reworked its Government structure

Last month, voters in Kenya went to the polls to vote for President, parliament and county officials. This east African democracy is home to a large number of ethnic groups and has struggled with ethnic-block voting in previous elections. However, while Kenya has struggled at times, especially with racial violence following the 2007 election, the nation has been able to retain its democratic principles. I covered the 2017 election in this previous blog, and now want to take a look at the 2022 vote, as well as offer more background into Kenya’s politics.

Background to 2022

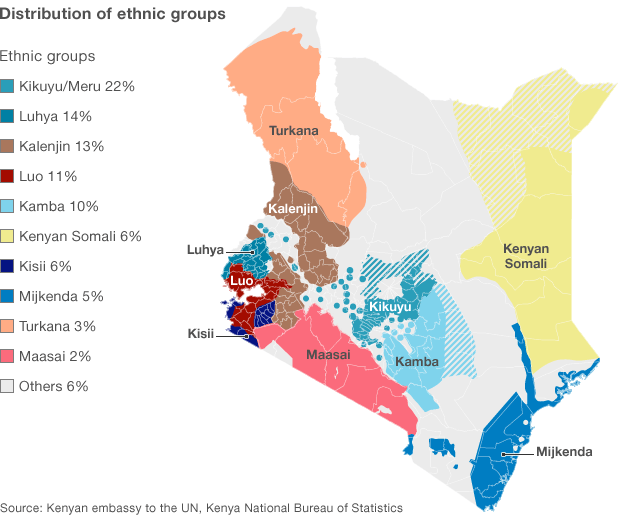

As stated above, Kenya is a very diverse nation. While the vast majority of the population is Bantu or Nilotic, the country is made up of no fewer than 70 tribes/nationalities that fall under those prominent language/racial groups. The largest ethnic group is the Kikuyu, which only make up 22% of the residents.

As a result of this fractured ethnic map, Presidential candidates in the past have worked to build coalitions based primarily on tribal loyalty; rather than political ideology. This has led to a great deal of negativity and violence; with groups pitted against each-other for resources. This has trickled down to local government as well; especially after Kenya devolved more power to its counties. The phrase “It’s our turn to eat” references the mentality of candidates/officials who work to reward the ethnic tribes that back them with government resources once in office. This not only leads to corruption, but resentment and violence.

The nation’s simmering issues erupted after the 2007 election; which has since been declared manipulated. After Incumbent President Mwai Kibaki “defeated” Raila Odinga in an ethnically-polarized vote; ethnic violence erupted for months - resulting in over 1,300 deaths. The violence, which was dominant in the Rift Valley province between the Kalenjins and the Kikuyu, was finally ended with agreement between Odinga and Kibaki that set up a coalition government. Odinga was made Prime Minster and a coalition cabinet was formed. A new constitution, which reduced the powers of the presidency and devolved powers to counties, as well as guaranteeing a litany of civil rights, was approved in a 2010 referendum. A great breakdown of the constitution and its rights can be seen here.

The Rift Valley, the site of so much ethnic violence, rejected the amendment. Why? The biggest issue was land. The fertile area is the site of many instances of land being offered up to individuals/groups for political support. The result is a very unequal distribution of land among the population. Many Rift Valley residents worried that the new constitution would lead to a redistribution of their land. Education Minster William Ruto, a former ally of Odinga (who was backing the vote) - led the NO campaign.

Two social issues drove votes, but land is widely seen as the major driver of the no campaign. The first was abortion being listed as a medical right in the constitution. This was cited by opponents, but it did not stop the referendum from passing despite the large religious population. The second social issue was the constitution setting up more roles for Muslim kadhi courts; which are courts that deal with Muslim laws around inheritance, marriage, and family. Rulings from these courts can be appealed to the higher-up secular courts. These courts exist to ensure Muslim integration into the largely Christian nation. The heavily Muslim areas border Somalia, where insurgents linked to terrorist groups have filtered across the border. These courts are part of an aim to short-circuit any terrorist recruiting effort; which usually start by convincing civilians they are persecuted by their government.

The success of the referendum set the stage for 2013 elections; which would be for President, Parliament, and local elections. This election, and those moving forward, saw the creation of the 47 counties; which have devolved/local powers. The constitutional also set up mandates for gender, youth, and disability representation among party lists for the parliament. The goal of the new constitution’s election structure was to make Kenya’s Presidential contest not so critical that it would lead to violence from the losing side.

2013 and 2017 Elections

In the 2013 elections, Uhuru Kenyatta defeated Raila Odinga in a very close and polarized election. Kenyatta, son of the first post-independence President, had William Ruto as his vice President. Odinga, meanwhile, has Kalonzo Musyoka has his VP. Kenyatta is of the Kikuyu tribe while Ruto is Kalenjin. Odinga is Luo while Musyoka is Kamba. These tickets covered 4 of the top 5 ethnic groups in the nation.

After the 2013 race, the 2017 contest saw the same two tickets face each-other. Both elections saw Kenyatta emerge victorious. However, both races saw many counties give 80-90% shares based on ethnic block voting.

The difference in the two elections was largest in regions with smaller ethnic groups. The major ethnic blocks represented by the candidates remained largely the same. I recommend checking my 2017 article for more detailed looks at the 2013-2017 comparisons.

These races were extremely polarized and saw Odinga claim fraud. The 2017 election was eventually annulled by the Kenya courts. The ordered re-run was not due to proof of fraud, but rather improper handling of election material; which certainly could have been a result of efforts to commit fraud. However, Odinga refused the re-run and encouraged his voters to boycott; leading to Kenyatta taking 98% of the vote. Despite this controversy, widespread violence did not erupt like it had in 2007. Local and parliament votes generated far less controversy and likely mitigated the desire for violence.

2022 Election

The 2022 election was a contest between VP William Ruto and opposition leader Raila Odinga. Yep, Odinga was running again. However, the circumstances this time were very different. Odinga had the backing of outgoing President Kenyatta. This came in the aftermath of a 2018 alliance the two formed after the 2017 controversies. While it could be viewed as a moment of national unity, its also been widely shown to be a self-interest deal between two powerful Kenyan politicians. The wide speculation around the alliance is that it served as a way for Kenyatta to avoid the risk of investigation for corruption and abuse (Kenyatta has had a very nasty relationship with the judiciary) by a politician he backed. While such an alliance could seem so unlikely considering the history, shifting coalitions of politicians and ethnic groups is a common move in Kenya.

This below graph comes from The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; who offer a hyper detailed look at Kenya’s politics. (Click the image below or high-res details)

Theoretically, Odinga, who already had a base of support, getting the backing of Kenyatta, should have made him a shoe-in for the post. Ruto, however, has much more support with younger voters; which is a critical voting block in a nation where over 90% of the population are under the age of 55. Kenya, like so many nations, has been hurt by the COVID pandemic and the post-COVID supply chain issues. Housing, prices, and jobs are all major problems. Ruto being forced to run without his bosses support allowed him to campaign on the problems in the nation; while Odinga effectively was saddled with Kenyatta’s legacy. Ruto took a decidedly populist stance in the race. Kenya’s election was largely dominated by economic concerns, with less overt ethnic-driven appeals (at least loudly). However, the results still showed heavy ethnic block voting.

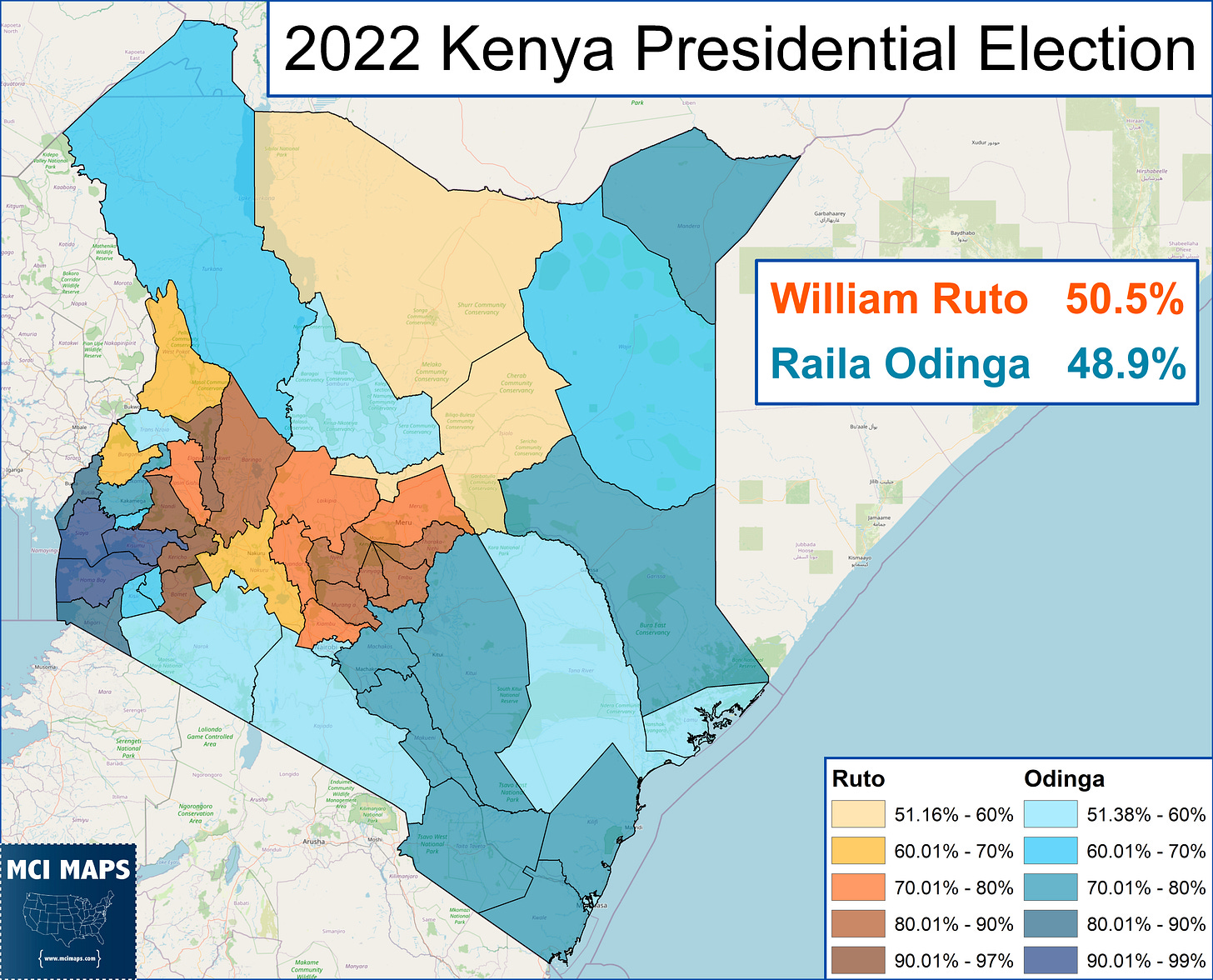

The results took several days to process, but in the end, William Ruto narrowly edged Odinga for the Presidency.

The results map is very similar to past races. Odinga only flipped a few counties from 2017, but did make improvements across much of the nation. However, he also lost ground in other counties, and in the end was not able to make up the gap.

We do not have solid data on ethnic % by county. However, based on available data, there is evidence of some shifts in ethnic coalitions.

Kenyatta’s backing did move some of his tribe. Kikuyu-heavy counties saw swings of 15-20 points to Odinga from 2017. Ruto still overwhelmingly won these areas though. Both VPs, Ruto with Rigathi Gachagua and Odinga with Martha Karua, are members of the Kikuyu tribe.

Kenya Somali counties, which are heavily Muslim, had the largest swings to Odinga. This makes sense considering Kenyatta’s support there in 2017, the lack of any candidates having ties there, and Ruto’s opposition to the constitution from 2010.

Ruto made sizable gains with Luhya heavy counties in the west end of the state. Ruto flipped Bungoma county after Odinga dropped by 32% in the county, the largest drop for Odinga.

You can see my full data table below.

Odinga challenged these results as well, but the Kenya Courts rejected the challenges. Fact checkers have found accusations of manipulation to be without merit. After the court rejected the challenge, Odinga conceded.

Meanwhile, the parliament results gave both sides nearly the same number of seats, with Odinga’s coalition narrowly edging Ruto’s. However, independents hold the difference in the chambers. On top of this, the county governor results ensured that counties on the opposite side of the Presidential winner still have local control. Again this pluralism and federalism mitigates the risk of violence.

Looking Forward

Kenya continues to have heavily polarized and close elections. However, the nation’s reworked government structure; with makes the Presidency less life and death, has no doubt aided in avoiding a repeat of the 2007 violence.

Kenya has managed to retain not just its democracy but avoided the widespread violence of the past. The nation, like so many, still struggles with corruption and tribal animosity. However, its reforms have greatly aided the nation in reducing bloodshed and moving forward as a democracy.