Issue #258: Racially Polarized Voting in Concordia's Election for Coroner

Coroners and Race in Louisiana

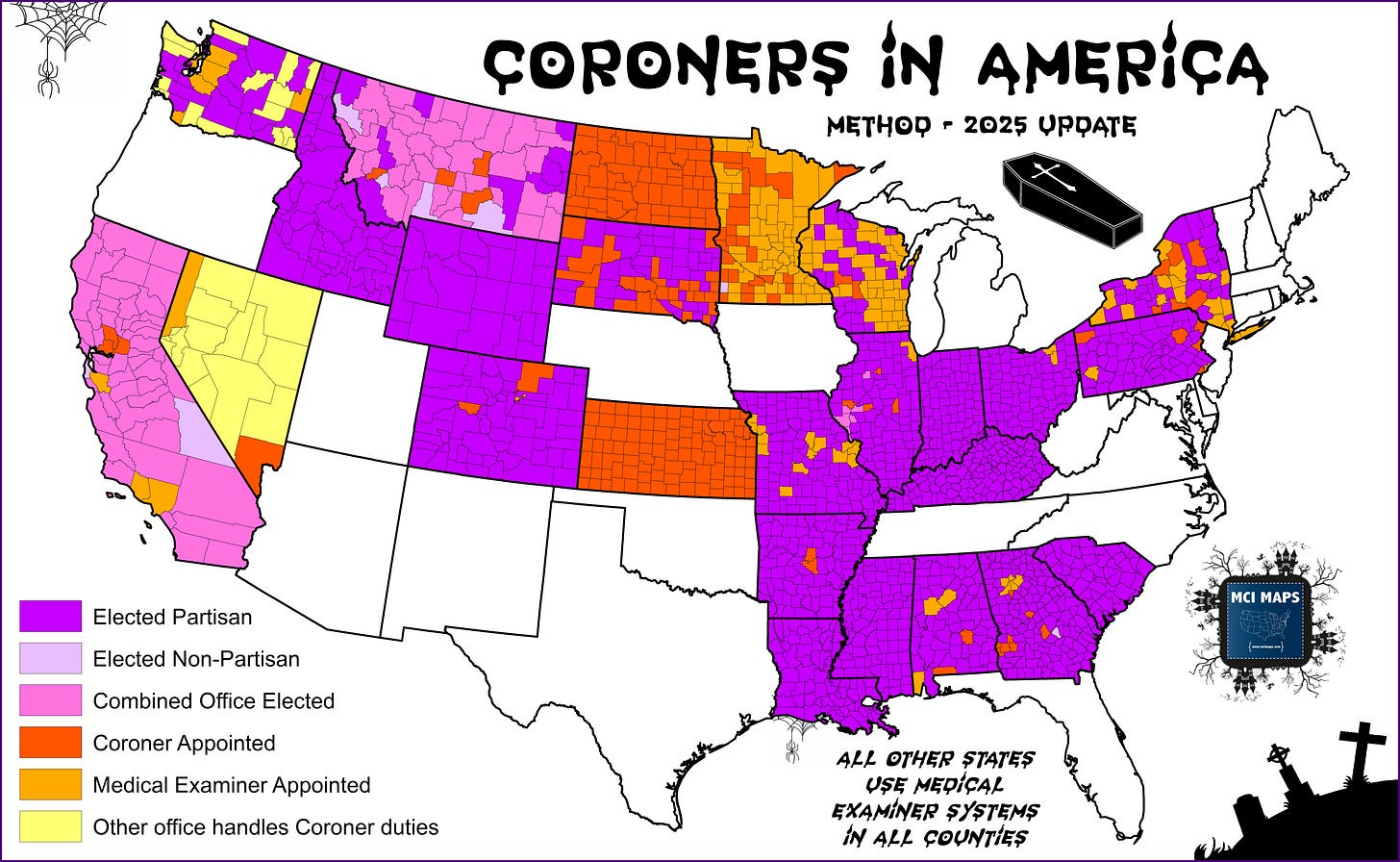

Anyone who’s followed me in recent years knows that I am very interested/obsessed with elections for County Coroner. You may not know this, but in America over 1,000 counties still elect their county coroner directly. You may live in one of these counties, but have never seen the race on your ballot due to incumbents often winning unopposed. People are shocked to learn that in over 95% of these counties, the position of coroner is elected on a partisan ballot.

What does party affiliation have to do with being coroner? I get asked this all the time. The answer is nothing. However, coroner, like your county clerks, county sheriffs, and county commissioners, are very often elected on partisan ballots.

Depending on the state, the role of the coroner can vary wildly. Some states require coroners to have medical backgrounds, or complete training once elected. In some states the coroner is involved in investigating deaths, in others they largely exist to deal with transport and storage of the deceased, and in others they are more directly involved in medical work. Their work varies. More and more, however, states have moved away from the archaic coroner system and moved toward Medical Examiner systems; which don’t involve elections.

The state of Louisiana, however, is still firmly in the business of electing coroners to every county, or should I say parish, in the state. This article will look at once coroner race in the rural parish of Concordia, and the racially polarized voting dynamics that emerged from it.

Louisiana’s 2023 Coroner Elections

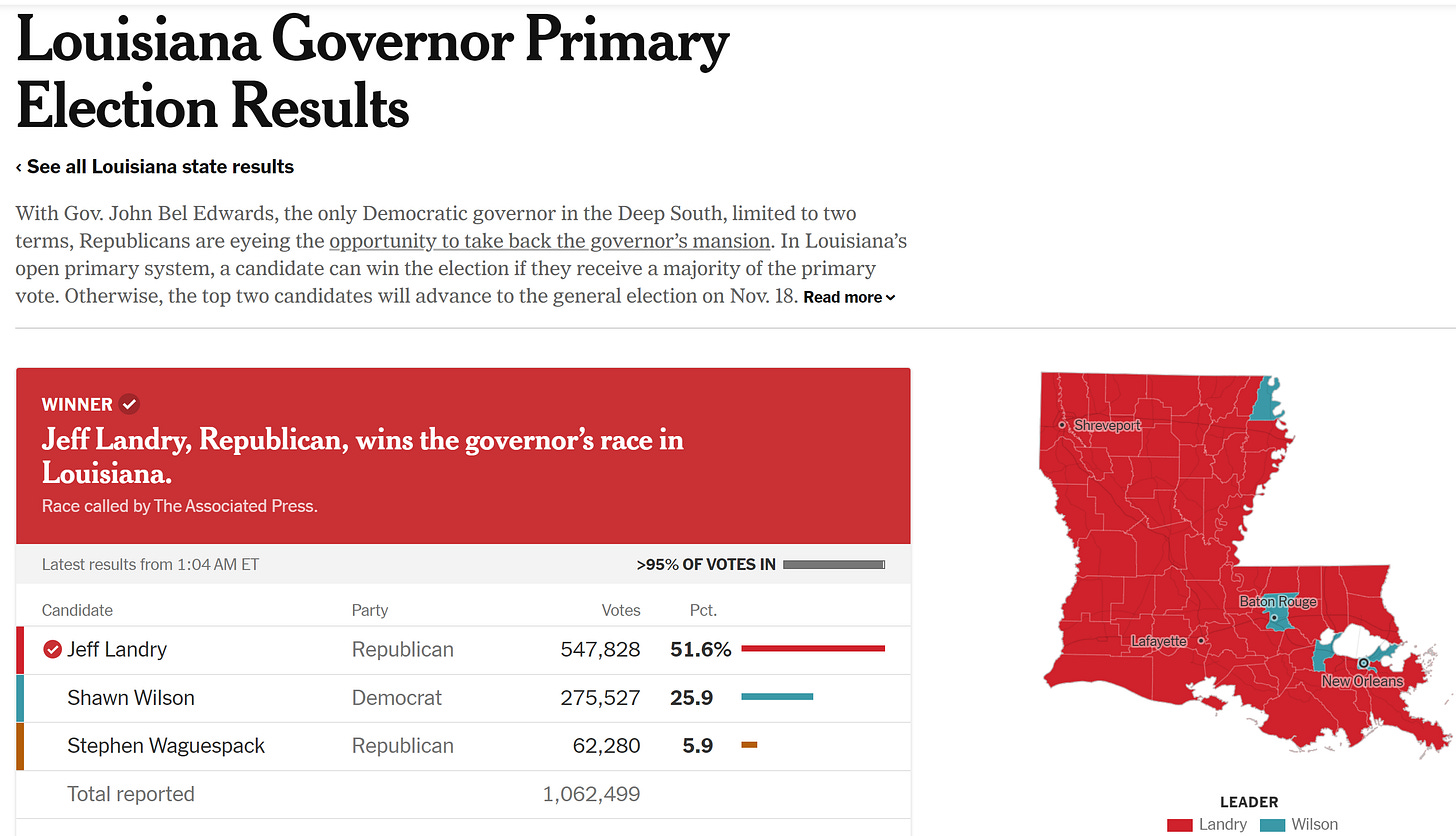

Back in October of 2023, Louisiana held its state and local elections. Louisiana, for those who don’t know, is one of just a few states to hold its elections for Governor, legislature, and other non-federal contests in “off years.” Just like how Virginia and New Jersey are holding their state elections next week, in 2023 the states of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Kentucky held their state contests.

Louisiana’s statewide contests were largely battles between Republicans. With Democratic Governor John Bell Edwards termed out, and his victories in 2015 and 2019 seen as total exceptions to the Republican dominance in the state, everyone know Republicans would regain the Governor’s mansion. Since Lousiana ureses a “jungle primary” system, where everyone runs on one ballot regardless of party, the only question was if Jeff Landry, then the state AG, could secure 50% and avoid a runoff for Governor. He did indeed avoid that runoff.

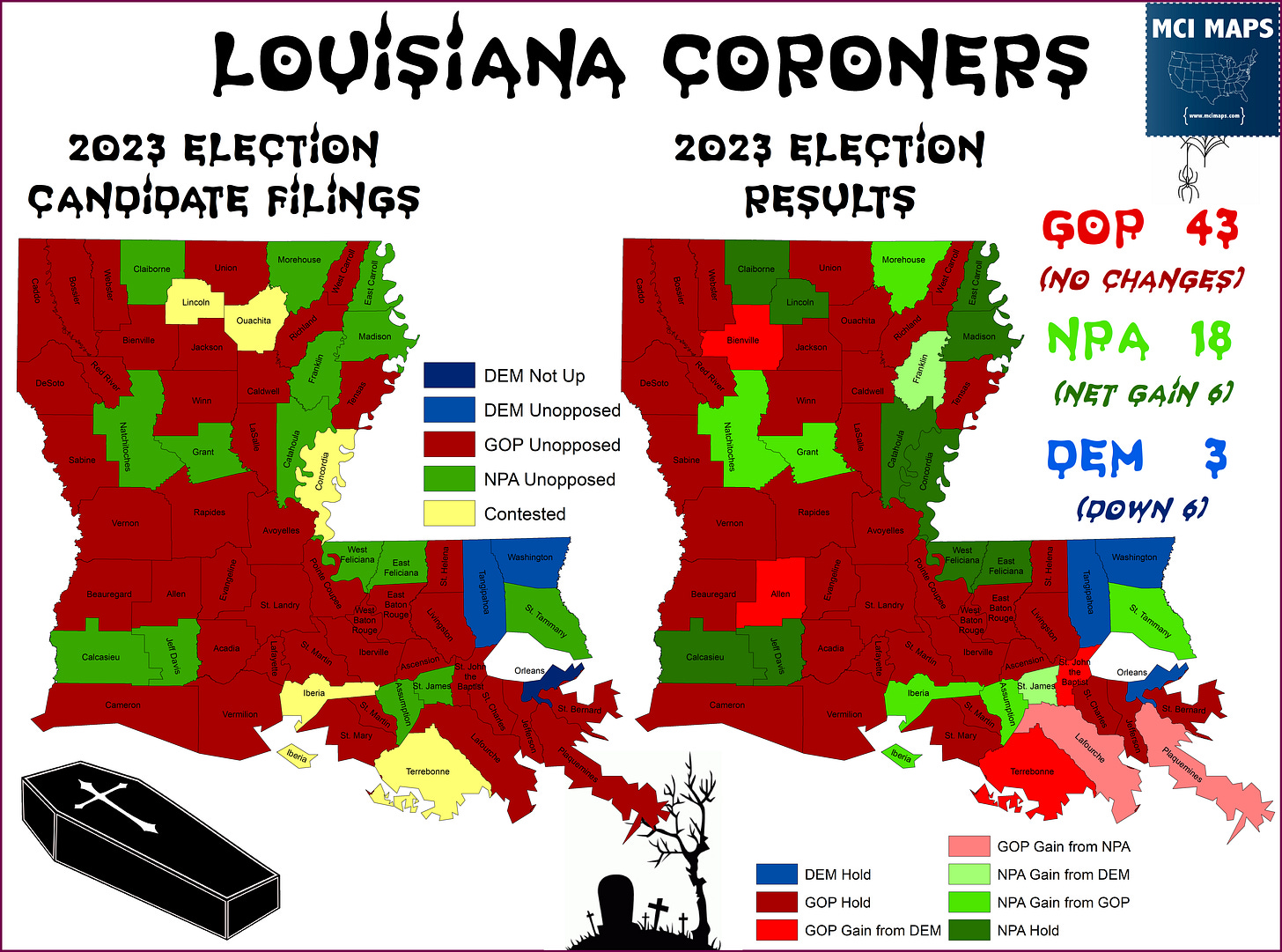

Amid these statewide races were local contests across the state. Parishes were going to the polls to elect commissioners, sheriffs, and you guessed it - coroners. I actually covered how these races went back in 2023, doing an election for the Halloween season just days after Louisiana went to the polls.

The elections for coroner were held in every Parish except for Orleans; which instead holds its county elections in the 2021, 2025, 2029 cycle. This still left 63 parishes needed to elect a coroner for its locality.

Once all the contests were finished, the result was Republicans maintaining the massive lead they held before. Meanwhile, Democrats shrunk to just three postings. The big story was independent candidates securing 18 parish coroner posts! I break down the results in my 2023 article.

Only one party flip was the result of an incumbent losing re-election, with the rest being party switchers or open seat. As the map above shows, a vast majority of parishes did NOT have contested races for coroner. This is not surprising, as the post does not generate crowded candidate fields. Incumbents often win unopposed, and even open races often see only one candidate file - especially if the state has training mandates for the post. Louisiana, for example, requires its coroners to be licensed physicians. This notably lowers the pool of candidates.

The other notable factoid is that independents make up a solid share of coroners in Louisiana. To be clear, these races are still partisan affairs, and people could run as Democrats or Republicans. Independents, at the local and state legislative level, do better in Louisiana thanks to its jungle primary system, as it allows candidates to run without voters feeling they must be strategic voters and stick with major party candidates.

This dynamic has also led to several parishes having elections where all candidates opt to run as independents. Especially as a mentality exists that some races don’t need to be partisan. Concordia was one of these parishes, as both its coroner candidates would run as independents.

While the race was fairly quiet on its surface, the results revealed a very racially polarized result. That issue of racial polarized has come up in great deal as Louisiana deals with redistricting lawsuits that revolve around the Voting Rights Act.

Before getting into the coroner race itself, lets talk a bit more about Concordia.

Racial Voting in Concordia Parish

Concordia is one of many rural and often-forgotten parishes in the state of Louisiana. The parish sits in the northern panhandle of the state; bordered by the Mississippi River.

The parish is only home to around 18,000 people. Over 15,000 of that live in the top north end of the parish; namely in the towns of Ferriday and Vidalia.

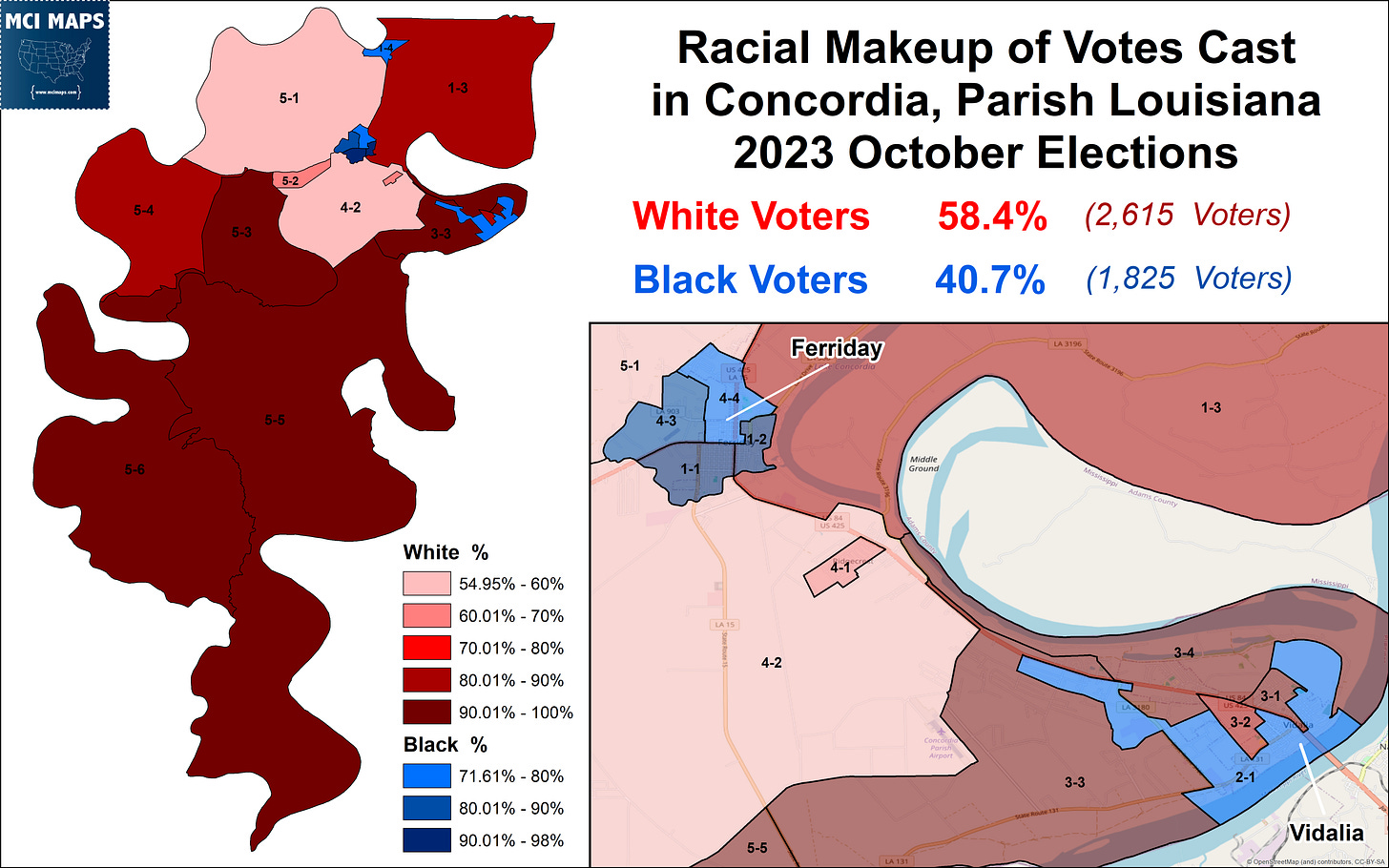

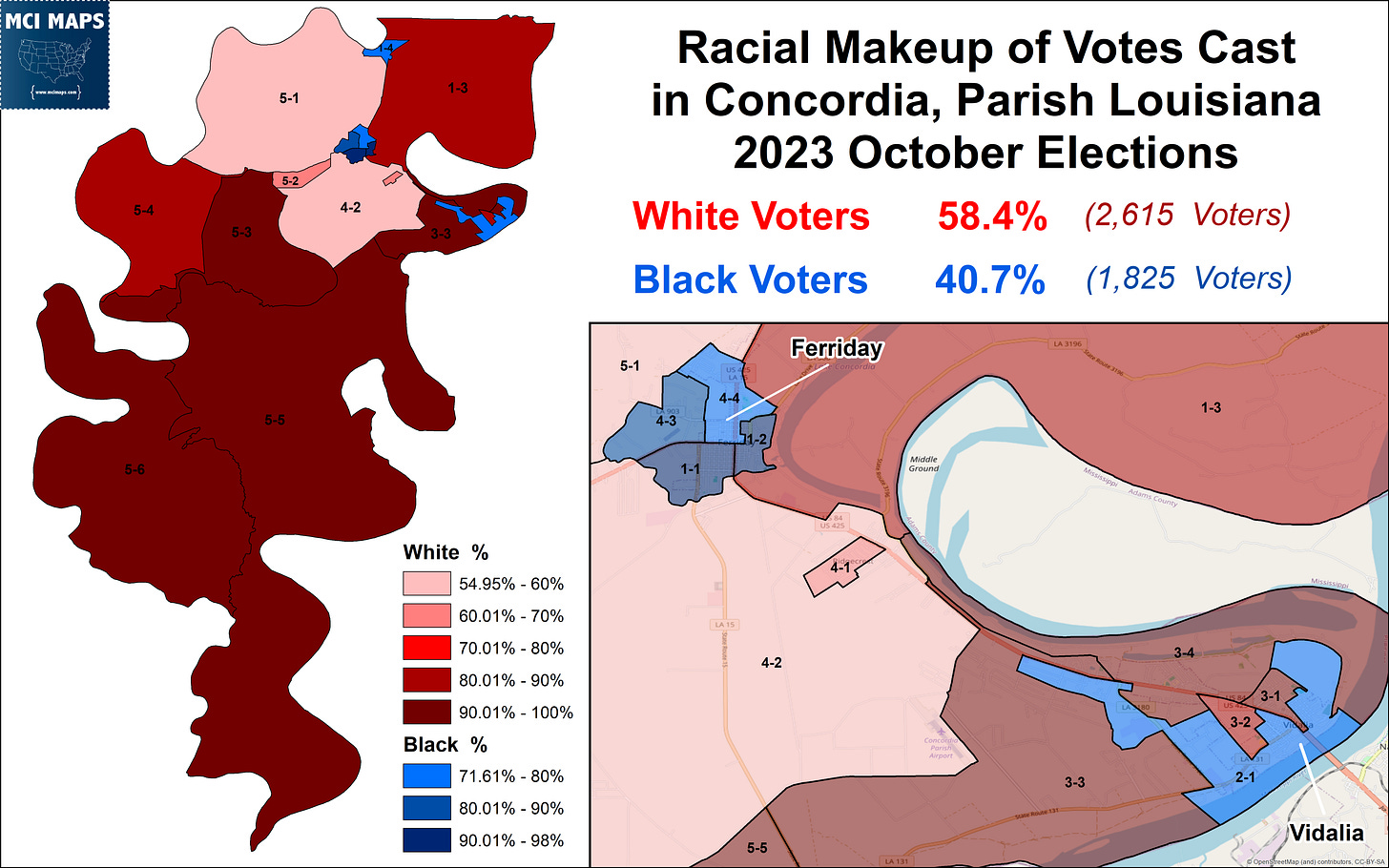

Concordia, like many parishes in the region, is majority white but also has a sizeable Black minority. The 2020 census gave Concordia a population that was 54% white and 40% Black. Thanks to higher turnout and registration rates, white voters made up 58% of the vote cast in the 2023 elections. Here you can see that the Black population is almost universally clustered in the north end of the parish.

With Concordia’s sizeable Black minority, the county has been incredibly racially polarized in its voting. This is a common trend in deep-south states, those part of the former Jim Crow racial caste system. Rural areas like this still largely see elections fall on racialized lines, specifically with Black candidates struggling to ever top 20% of the white vote.

Even at an era where Louisiana was more Democratic-leaning, Black Democrats could not win enough white voters to secure victory. While white Democrats could win offices like Governor or Senate in the 1990s and 2000s, Black Democrats could not. In the modern era, however, as party voting has become more racially polarized, even white Democrats struggle to top 25% of the white vote in the deep south.

This dynamic is something I delved into more in my article from last week on the Voting Rights Act and Louisiana redistricting. While that article is mainly focused on why Louisiana’s Congressional map is shaped how it, I also delve into the VRA and issues of racially polarized voting.

Concordia has shown a long history of racially polarized voting in both the past and present.

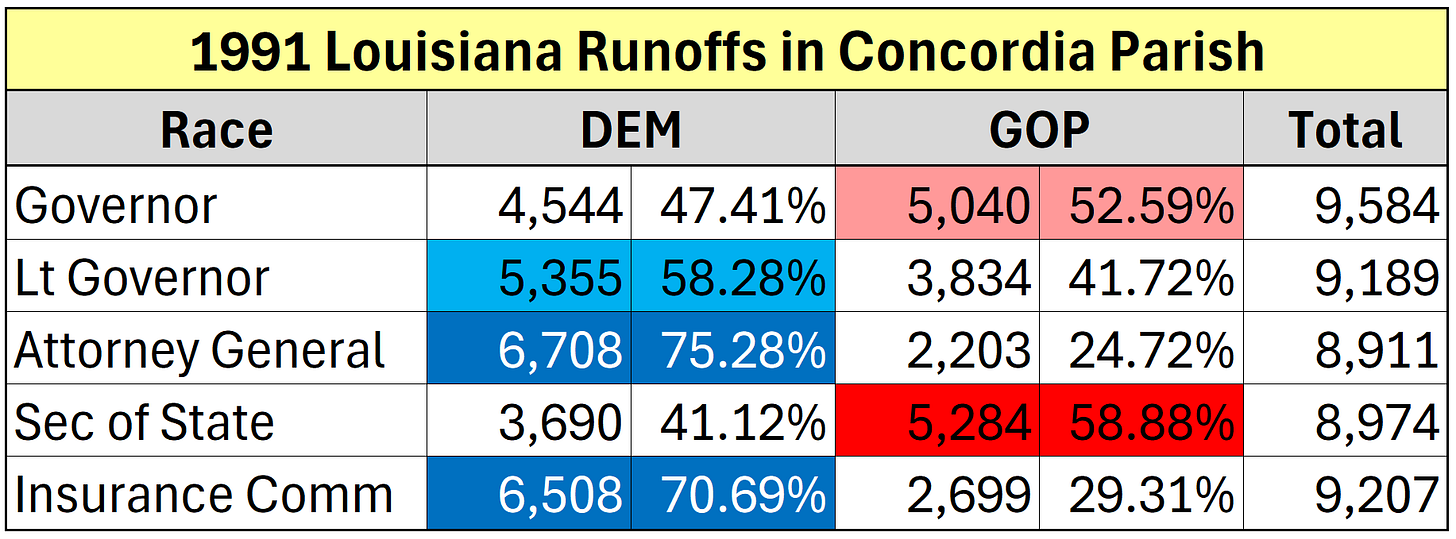

In 1991, it was one of a batch of panhandle counties to vote for David Duke in the infamous Gubernatorial contest. Duke, for those who don’t remember, was a former Ku Klux Klan leader that, despite claims he’d “reformed”, still ran on a white grievance campaign. He’d famously say he wasn’t racist, he was just “pro-white.” Duke would lose statewide with 39% of the vote. In Concordia, however, he would win 53%.

At the same time it voted for Duke, the parish went Democratic for all other races except Secretary of State. That race is unique too, as the Republican was W. Fox McKeithen, a popular official who initially was elected as a Democrat in 1987 and would go on to serve as Secretary of State until his death in 2005. Democratic candidates otherwise excelled in the county - except in the case of Governor.

Democratic candidate Edwin Edwards won statewide over Duke with a coalition of Black voters and moderate whites. In his loss, Duke would brag that he at least “won the white vote” - which he did with vote shares between 55% and 65% depending on socioeconomic bracket. In many of the rural parishes with sizeable Black minorities, Duke’s vote share among whites was much higher - revealing racial animus in these counties - many filled with white voters from the Jim Crow era.

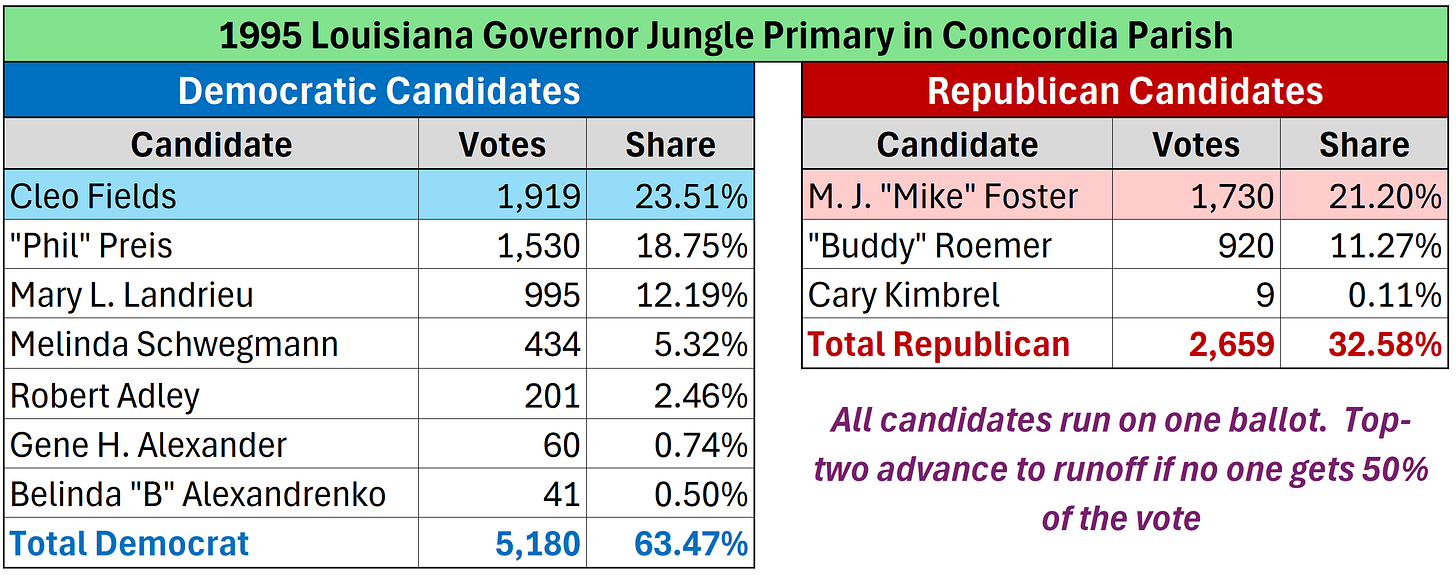

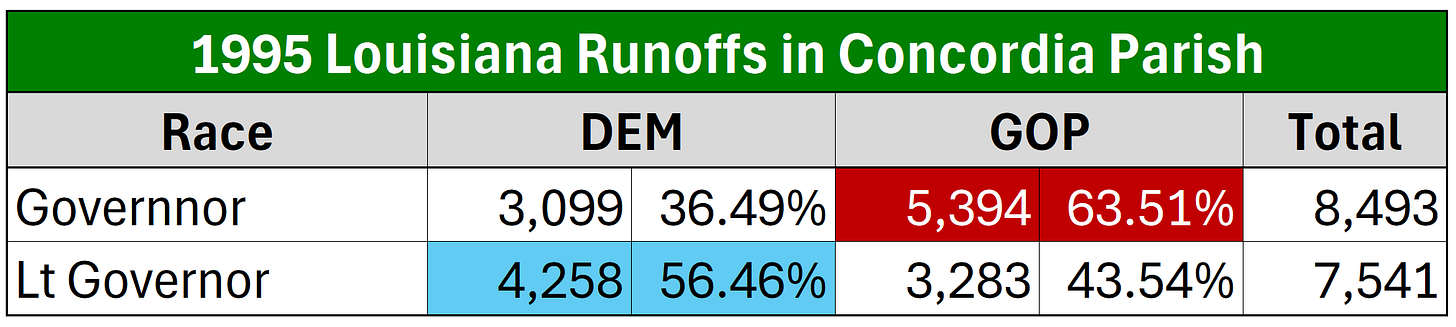

The 1995 Gubernatorial election saw another example of racially polarized voting in Concordia. That year, Black Congressman Cleo Fields ran for Governor. In the first round, which uses that Jungle Primary system discussed before, Fields and Republican State Senator Mike Foster advanced to the runoff. In Concordia, over 60% of the vote cast went to Democratic candidates, as seen below.

Fields would go on to lose the runoff badly to Foster. Fields was unable to consolidate support from many white Democrats, who instead went to Foster. This was further evidence of Louisiana’s racially polarized voting. In Concordia, the story was the same. Fields lost the parish easily to Foster. However, that same day the parish voted Democratic down ballot.

This dynamic would continue in Louisiana and Concordia Parish specifically. Now in the modern era we have seen Lousiana become a firmly Republican state, though white Democrats do still outperform Black candidates in modern races.

Anyone who thinks racial voting isn’t still an issue in Concordia needs to look no further than their coroner election two years ago.

Concordia’s Coroner Election

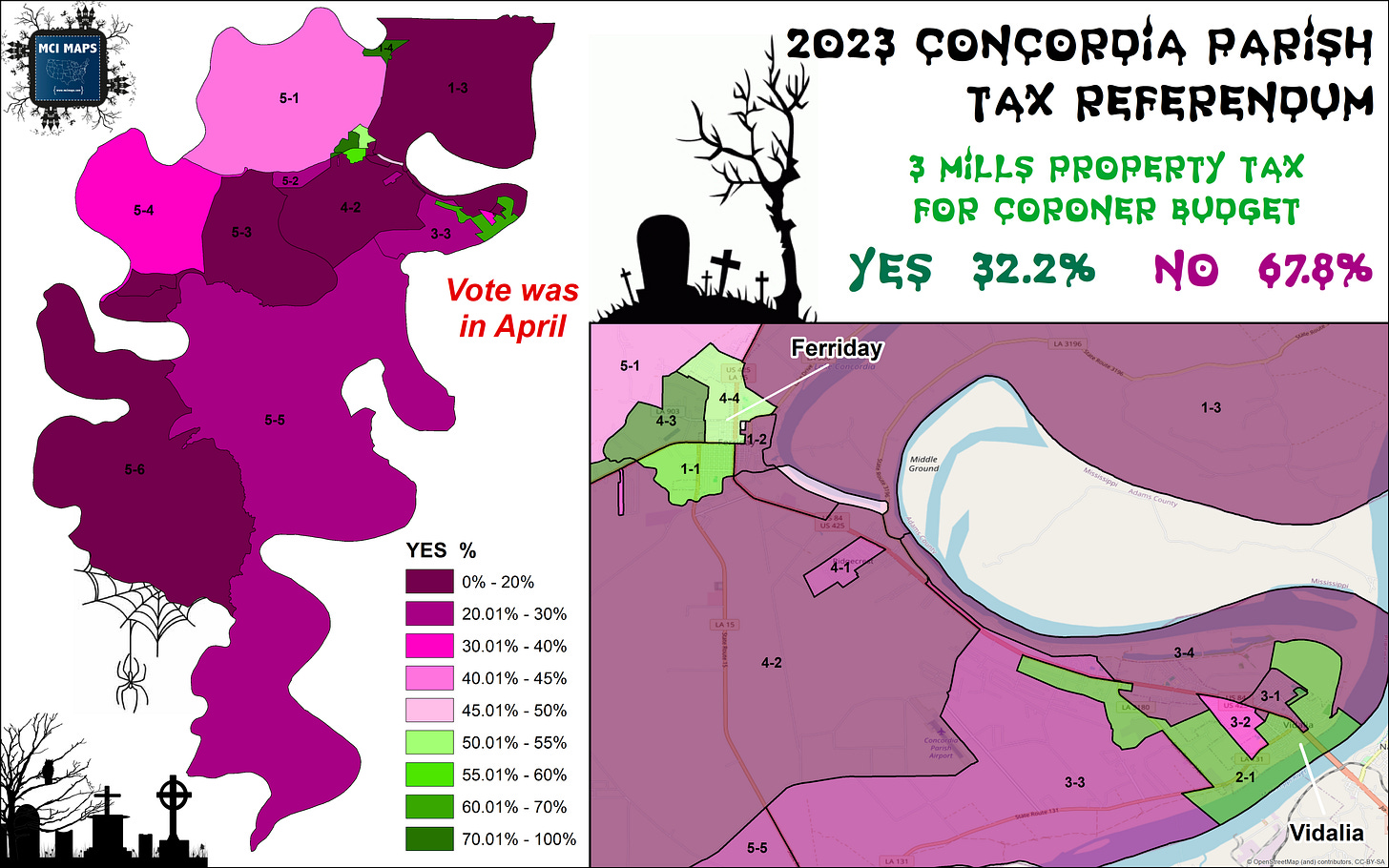

Heading into 2023, Concordia’s coroner office was mired in political tension. The incumbent Coroner, Dennis LaRavia, an independent himself, opted not to run for re-election. The reasoning was the failure of an April property tax referendum that was designed to increase the coroner’s office budget. As this article lays out, LaRavia was right that the budget for the office was far too small to meet the demands of the office. LaRavia had even notably paid for a deputy out of his own pocket. Despite this, most politicians and leaders in the parish pushed against the referendum, which easily failed.

Notably, the measure only succeeded in the more heavily Black precincts, while white areas rejected the measure. This is likely down to political attitudes. Black voters, and hence Democrats, are more in favor of such referendums, seeing it as a reasonable ask. White voters, now more Republican than ever, are more locked into a libertarian anti-tax sentiment.

LaRavia felt that the failure was at least partially due to dislike for himself by different community leaders. In his announcement, he said that he did not have support of the county’s police jury (note this is the Lousiana version of county commissioners) and that he felt the best course of action was to let a new coroner push for updated budgets.

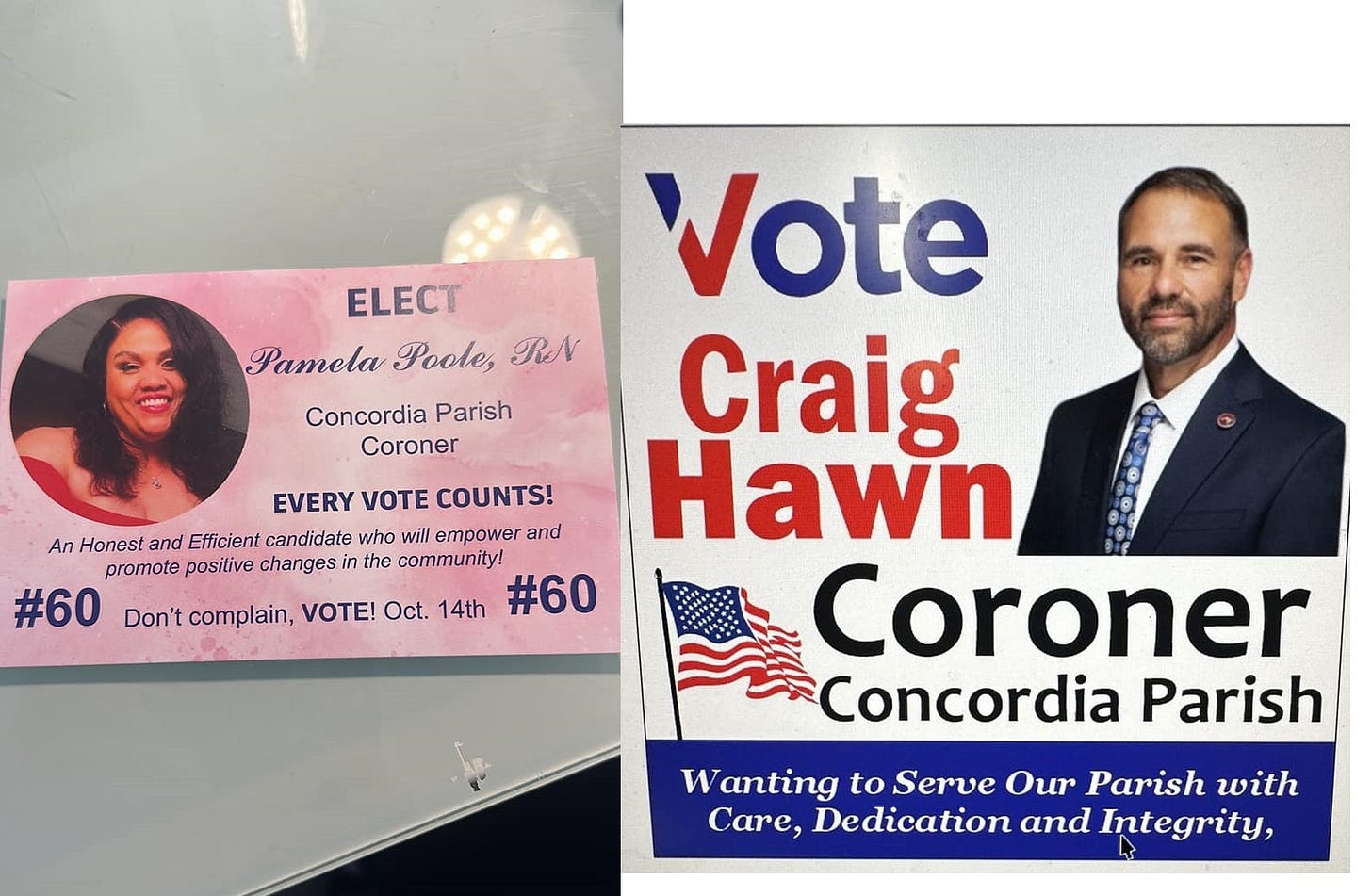

With the open race, two candidates filed for the post.

Pamela Poole, a Black woman and a registered nurse

Craig Hawn, a white man who worked for a funeral home

Per state law, both were licensed to practice medicine to even qualify to run.

There is very little discussed about the race online, as best I can find. This is not uncommon with smaller counties/parishes. Clearly nothing scandalous happened to warrant news, with local papers largely just reminding voters of campaign forums and who was running. I only managed to track down some actual advertisements by searching through Facebook.

The only news of note I can find for the race is that Poole was formally endorsed by the Southern Poverty Law Center Action Fund. In their endorsement, the SPLC stated…

“While there is often not a lot of attention paid to the position of coroner, it is of incredible importance. It is essential that those who serve in this position put fairness and transparency first. We believe Ms. Poole will do just that which is why we are endorsing her.”

As best I know, this endorsement didn’t come with any or much financing for the race. Many of these endorsements are up to the candidate to utilize in spreading their message as they see fit. It does reflect a the SPLC, often seen as focused on national events, is also focused on down-ballot races.

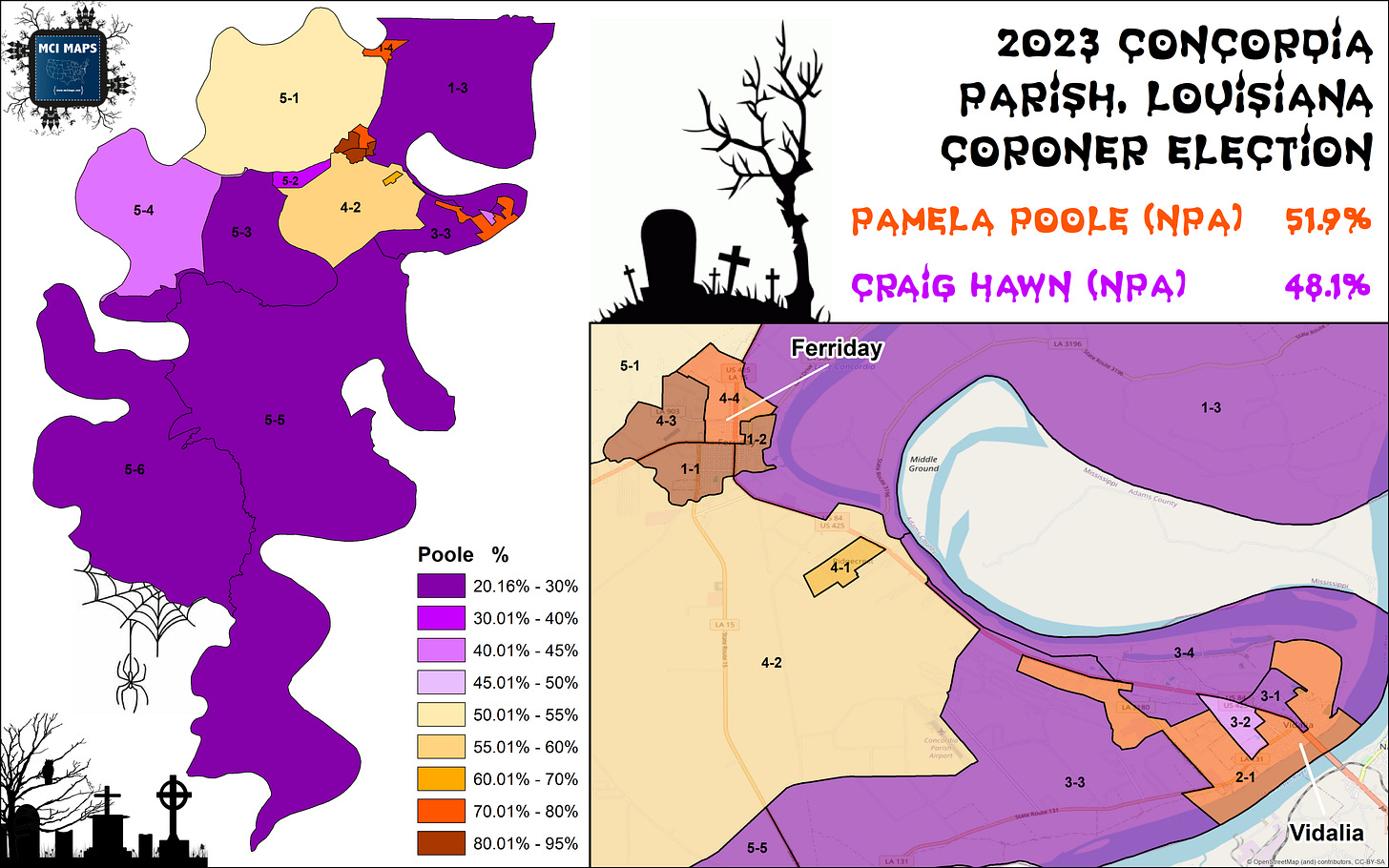

As I alluded to at earlier in this article, when the results came in, they revealed a very racially polarized vote. However, while the vote was very polarized, Pamela Poole was able to narrowly squeeze out a victory in the race.

Poole eeked out a win by doing very well in the Vidalia and Ferriday communities. Meanwhile, Hawn was strongest in the even-more-rural portions outside these towns. For reference, here is the racial makeup of that night’s vote, as seen earlier in this article.

If you look back and forth at the election map and the race map, they are nearly identical, just with different color schemes.

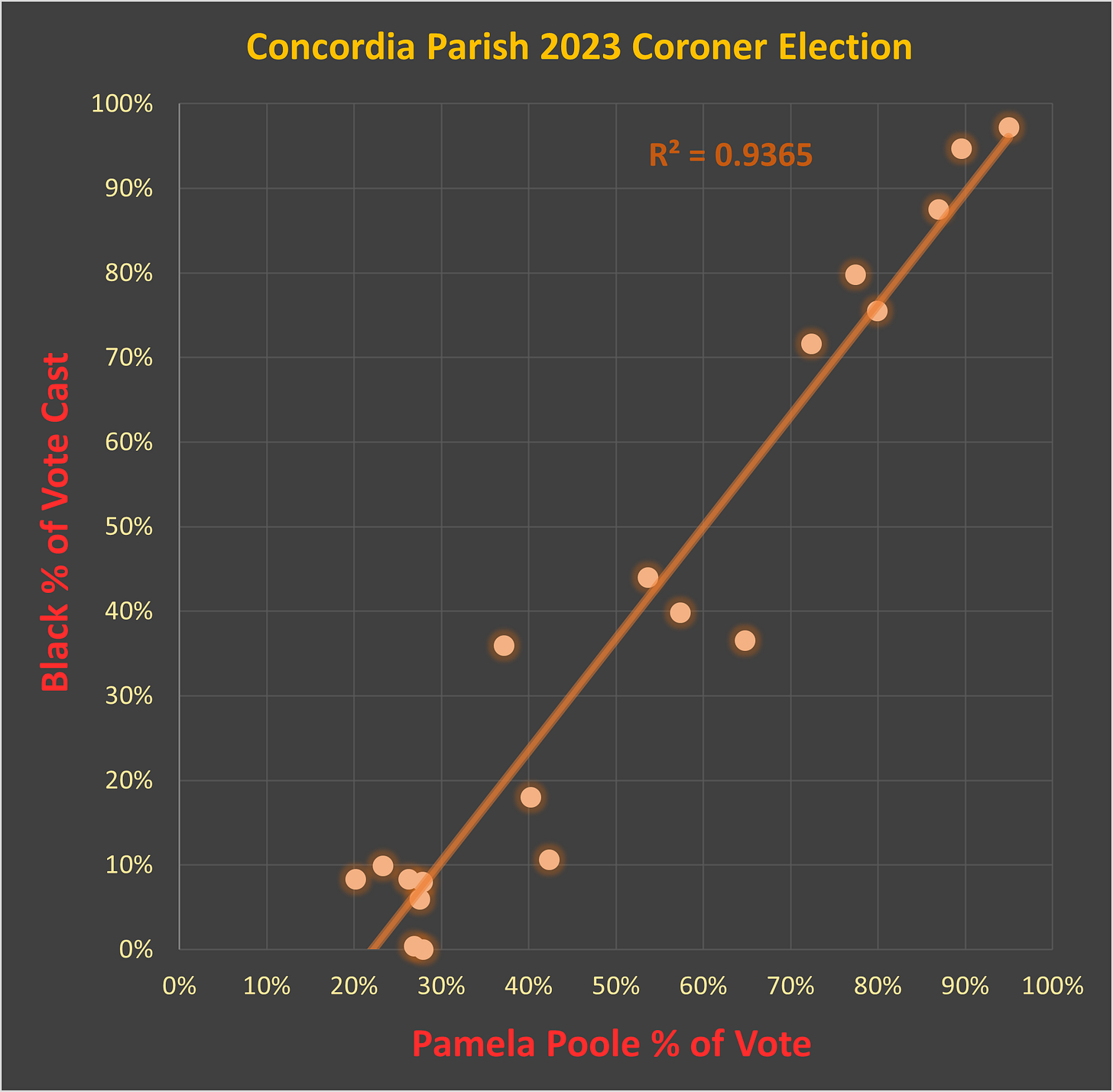

Indeed, the correlation between the election and the racial makeup of the vote is very high. If we plot out Poole’s share of the vote with the Black share of the vote cast, the correlation is 0.93; indicating a very high correlation between race and candidate support. For reference, a 1.0 would mean a perfect correlation.

The correlation means that Poole was able to win almost all of the Black vote, however, Hawn likewise dominated with white voters. Using the precinct data, I estimate that Poole secured 92% of the Black vote and got just 28% of the white vote.

Poole’s margin with white voters is actually much better than many other Black candidates have gotten. Granted part of that may be those races being higher profile and them running as Democrats. Poole’s showing with white voters was stronger than other Black candidates have faired. However, even with that fact, the racial polarizing in the election is quiet extreme.

The results show that, despite what some want to claim, we are not a “post racial” society. Racial Black voting, coupled with a history of discrimination in the form of Jim Crow, something only brought down a few decades ago, shows why laws like the Voting Rights Act are so important.