Issue #247: How Fraud in Miami's 1997 Mayor Election helped Dade County Change its name

Miami politics is always controversial

In the last several weeks, the city of Miami has become a lightning rod of controversy due to a decision to move their election date. Elections for Mayor and City council were long planned for November of this year, however, just a few weeks ago, the city council voted to move the elections to November of next year; the same time as the Gubernatorial election.

The merits of a different election aside, the move has generated pushback due to the late-timing of the change. Candidates have been filed for and running for months now, and the late change is now being subject to lawsuits and negative press coverage. I will have an article in the near future on the issue of municipal election dates and the benefits/drawbacks of aligning with statewide contests. For this article, however, I have a different topic to cover.

The drama and scandal around Miami moving elections is just the latest issue for the city. Miami has never been short on election controversies, but one story in particular stands out. In 1997, Miami had a mayoral contest that was so riddled with fraud, it was actually tossed out by the courts. Many Floridian politicos know of that story. What I don’t think many know is that Miami race may be the reason Miami-Dade County has the name it currently holds.

You see, as Miami was holding its election for Mayor, a countywide referendum to change “Dade County” to “Miami-Dade County” was being held. The county had voted on name changes several time, but 1997 proved to be the success name-change advocates had hoped for. However, I believe it can be argued that without the controversy of the Miami mayor’s race, the name change very well could have failed.

How could this be? Lets dive in. First, we will talk about Dade County and the push for a new name.

Historic Dade County

Dade County was initially established by the Florida territory in 1836; originally covering a vast swath of southeastern swamp land. The original county layout covers all of modern Miam-Dade, Broward, and a chunk of Palm Beach. Dade and Monroe county split the Florida Keys down the middle for several decades.

The original name for the county was going to be Pinckney County; named after Revolutionary War veteran, diplomat, and former Vice Presidential nominee Thomas Pinckney. However, as the county’s creation was being taken up by the Florida territorial legislature, the Second Seminole War broke out. At the outbreak of the war, a company of US soldiers, led by commander Francis L. Dade, were killed. The territorial legislature changed the proposed county to “Dade.”

Dade would remain a rural backwater county for several decades. In the 1840 census, its population was just 446 people. By 1900 it was still under 5,000 residents and its final border largely took form by 1920. The county’s population would begin to grow in earnest with the turn of the 20 century. The biggest driver was the expansion of the Flagler Railroad south of West Palm Beach. A major freeze in 1894 and 1894 decimated the state’s citrus groves but had not reached what is now Miami; then called Fort Dallas. The region suddenly became a more desirable destination, and the Flagler railroad expanded to Key Biscayne in 1896; the same time the City of Miami was established.

This marked a rush of migration and development. By 1920, Dade county was 42,000 strong, with 29,000 of that coming from Miami itself. From 1920 to 1950, Miami made up over 50% of the county’s population; with it peaking at 77% in 1930. After 1950, as development expanded to its north and south, Dade County saw continued growth. In 1950, Dade County had 495,000 people. Just ten years later, it was at 935,000. That same year Miami was at 291,000 people. While the city was no longer a majority of the population, in fact its under 20% today, Miami was the go-to name for the region; not Dade County.

The Fight over the Name

The push to change the county name kicked off in the post-WWII era. South Florida business leaders argued that the name was too obscure and that the area was broadly already seen as “Miami.” Despite these arguments, voters had little interest in changing the name.

Efforts to change the name of Dade county failed 6 times before success. Voters rejected efforts to change the name in 1958, 1963, 1976, 1984, and 1990; all by landslide margins. The 1994 vote, which would have changed the name to “Metropolitan Miami-Dade County” failed by a 13%-87% margin.

Voters had long showed little interest in the name change. However, as the 1990s went on and Miami grew in international reputation as a business and tourist hub, business and government leaders aimed for another chance to change the name. When Alex Penelas was elected county mayor in 1996, he made the name change a priority – believing adding “Miami” to the name would help him attract business and investment. Penelas was a dynamic politician for the time – a young Cuban democrat who was close with the business community of the county. With Penelas in the top job, the business community has a strong ally in the effort to change the name.

Penelas and the business community planned for a referendum to coincide with the November 13th, 1997 runoffs for city races. The referendum would be listed along two other minor questions and the mayor and city council runoffs for Miami, Hialeah, and Miami Beach. The fact this referendum would be held when these towns were holding their RUNOFFS, not their initial primary voting, is very important. We will get back to that in a moment.

The 1997 Referendum

The business communities raised just under $90,000 for a stealth campaign that largely ran ads in Hispanic and Black radio. Major businesses like American Airlines and Carnival Cruise Lines each gave $10,000. The goal was a quiet campaign that pushed the idea in the short window before the election day. As a result, no major debate took place and there was no organized opposition campaign. In addition, the Miami Herald, which had argued against every past name-change, opted to support the measure in 1997; arguing a change could help, but at worst wouldn’t hurt.

When the results came in for the referendum, the name change narrowly passed. By just a 4% margin, the county would change its name for the first time since statehood!

The measure passed in the city of Miami and along the Hispanic corridor that extends west. It narrowly passed in Hialeah. The proposal failed in the northern black precincts and in the south end of the county; including Homestead and Florida City.

The results were a shock to many voters, who didn’t even realize the referendum was happening. Voters, for the most part, seemed to shrug the change off, while the business community was thrilled. The lack of voter engagement can best be summed up by a Dade County courthouse employee saying “What do you mean the county’s name has changed? What are you talking about?” when asked by a reporter.

Supporters of the change were expecting, and counting on, a low turnout electorate. They got their wish. Just 13% of voters showed up for the referendum. As the turnout data shows, the bulk of the voters were not there for the referendum, but for city runoff’s being held in Miami, Hialeah, and Miami-Beach. You can basically see the outline of the three towns in the turnout map.

While the county had under 15% turnout, each of the three cities had turnout between 30-35%. The parts of the county not in the three cities saw a turnout of just 6%! This is also the area where it failed.

The referendum breakdown by the three cities vs the rest of the county can be seen below. Thanks to the turnout disparity, Miami made up 42% of the vote cast despite being just 16% of the registered voters. This referendum was dominated by the three cities holding election runoffs.

Most importantly, the referendum’s 5,400 vote margin in the city of Miami was larger than the 3,400 countywide margin. Without the higher turnout in the cities, the measure would have failed.

Note the absentee ballots results, about 10% of the vote cast, are not broken down by their respective precinct/city, so I included them as a separate total. The city referendum votes are therefore election-day only.

The name-change failed in absentee’s by almost 2-1. Half of these ballots came from Miami, though its unclear how the absentees would have broken down by each geographic area. However, there is alot more to be said about absentee ballots further into this article.

Miami Secured Victory

The city of Miami was instrumental in the measure passing thanks to its strong support and turnout. However, even in the city itself there was divide. The northern end of the city; which is heavily Black, was largely against the proposal. However, it was also an area with much lower turnout. The Mayoral runoff being held that day was between two prominent Cuban politicians, which I will get to more in a moment. That runoff race drove turnout up in the Hispanic areas; areas that also backed the name change.

Another way to highlight the importance of the Hispanic Miami precincts is to look at the margin’s by square mile (a type of density analysis). The Hispanic Miami precincts stand out from space – giving the YES camp a major block of votes to withstand losses elsewhere

So as mentioned, the turnout in the Hispanic portion of the city had such strong turnout thanks to the Mayoral Runoff between two prominent Hispanic candidates. We need to talk about that election and the absentee scandal around it.

The Infamous 1997 Miami Mayoral Election

The Dade name-change referendum took place the same year as the most infamous mayoral election in the city of Miami. It stands as one of the biggest fraud scandals for the state in the modern era. It eventually led to a court case that saw the results overturned.

The Miami mayoral election was a major heavyweight fight. Incumbent Mayor Joe Carollo was being challenged by Xavier Suarez, who’d served as mayor until retiring in 1993. Three other candidates, none serious, were also running. The race was nasty and vicious; with Miami’s finances becoming a major focus. Carollo is a fierce and controversial politician who had lost re-election to the city council in 1987. Carollo made a comeback, winning a city council race in 1995 and then a special election for Mayor in 1996 when Incumbent Steve Clark died of cancer.

Carollo had undergone an image rehabilitation in the 1990s, making amends with many black leaders after racist barbs in the 1980s and trying to reset his image as less combative and bombastic (that didn’t last). Carollo walked into the mayoral office in 1996, facing no real opponents, and immediately clashed with and fired the city manager, Cesar Idio. This firing, however, revealed a long history of corruption and debt with the city’s finances. The new manager uncovered over $68,000,000 in debt for the city. Idio would go on to be convicted of obstruction of justice relating to a kickback scheme. The reputation of the city was shattered. Its bonds became junk status and in December of 1996, Governor Lawton Chiles ordered the takeover of the city’s finances at Mayor Carollo’s request.

Suarez, who was not hit by the corruption scandal’s themselves, decried the state intervention and claimed Carollo was exaggerating the city’s problems. In September of 1997, just two months before the city elections, the residents voted to reject a petition-proposal to abolish the city itself. The proposal drew heated opposition from the city’s Cuban voters, who controlled government and saw it as a direct attack.

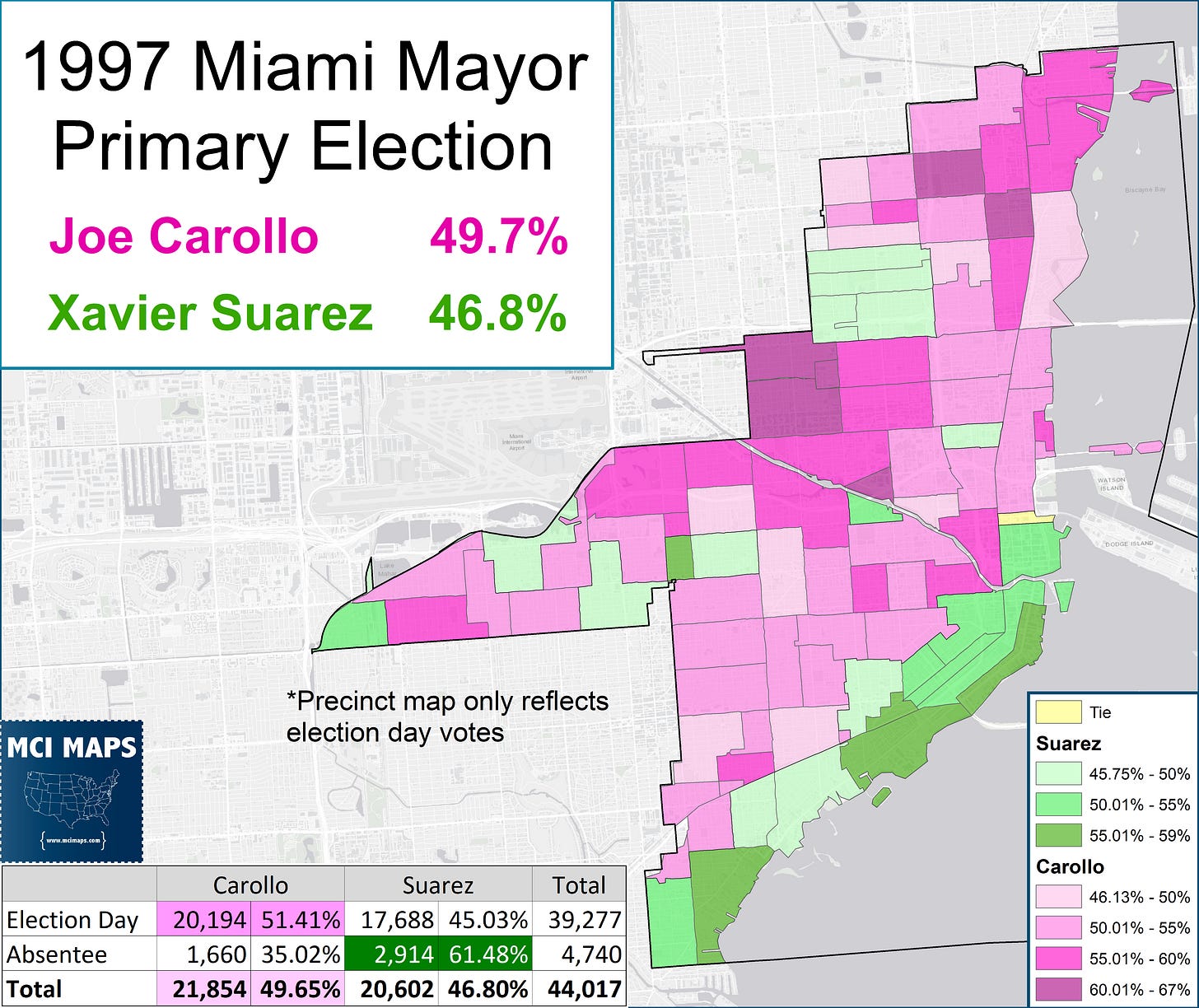

This drama set the stage for the November 4th Mayoral election. Suarez ran hard against Carollo, while the mayor used his stewardship as the justification for a full term in office. When the results came in, Carollo was just shy of the 50% to avoid a runoff. He’d actually secured the majority of election day ballots, but lost absentee’s almost 2-1.

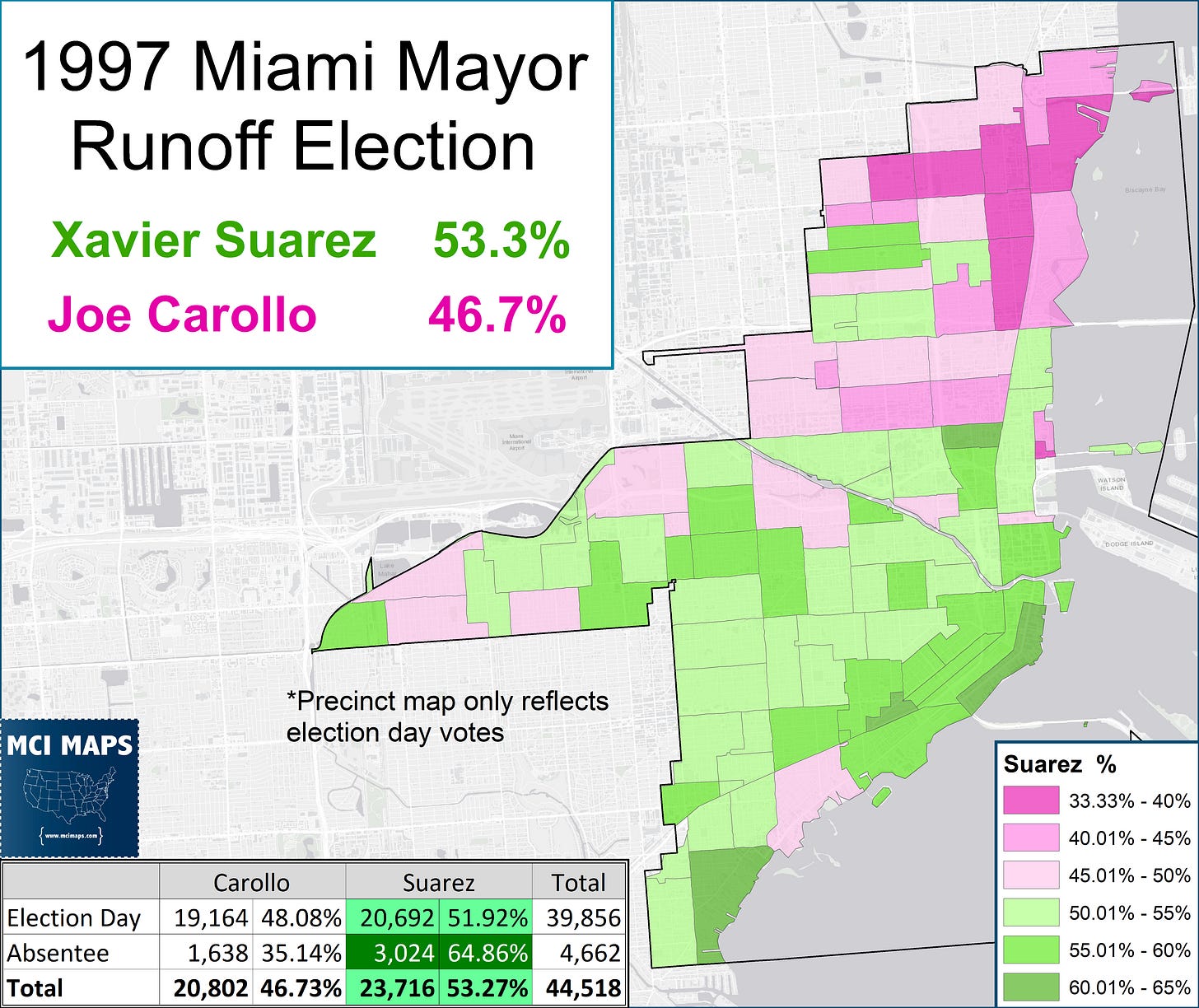

As a result, a runoff would take place less than two weeks later, on November 13th. Suarez would go on to win that race by a fairly comfortable margin. This was the same day as the Dade county name-change referendum.

The runoff and first round where largely contested in the Hispanic community and Spanish radio/literature. It was a clash of two prominent Cuban politicians and it resulted in Hispanics making up over 75% of the vote cast despite only being 50% of registered voters. It was thanks to that high turnout in Miami’s Hispanic corridor, which netted the YES side 5,300 votes, that the name referendum was able to pass.

Notably more ballots were cast for Mayor, 39,000 on election day vs the 30,000 for the flag referendum. Mayor was the main driver of votes; with many residents giving no attention to the county questions.

The runoff itself drove turnout for Miami. This is very important to note: had Carollo won outright on November 4th, Miami would have had nothing to show up for beside the name-change vote. The referendum itself was not a driver of votes – as demonstrated by the weak turnout in the non-Hispanic portions of Miami.

Without that contested runoff, turnout likely collapses in the Hispanic corridor, and the name change could very well have failed.

Absentee Ballot Corruption in Miami

Before the runoff for Miami mayor even took place, a major investigation was already brewing around the absentee ballots cast in the first round of voting. Reports began to emerge that volunteers and staffers with the Suarez campaign had engaged in absentee ballot fraud in order to secure their candidate a huge win – which forced the runoff.

Ballots were cast from dead voters, from voters who insisted they never asked for a ballot, people out of the district, and people who were bribed to offer their vote. The emerging scandal, which resulted in its first arrest of a Suarez worker within days of the first round, was nothing really new for Dade. “Ballot brokers” – as they were often known, would get paid sometimes $30 per returned absentee ballot. The election for Miami mayor generated hundreds of thousands raised and spent by the two candidates – all for a low turnout race. Plenty of money was free for such payments.

Ballot broker scandals included calling in requests for ballots for older voters, then picking them up at the addresses and filling them out. The tricking of elderly voters could best be seen in a quote from a 103 year old Miami Beach resident who, according to records, had voted absentee: “I’m not on top of things….. I have a citizenship card. I think maybe I voted, I don’t know.” Plenty of forged signatures were also discovered. Such scandals led to an election in Hialeah being tossed out in 1993 and efforts to curtail the shady practices were falling short by this point.

Several voters interviewed admitted they just turned in blank ballots to the brokers who offered to “take them off their hands.” A story out of Miami Beach’s Mayoral election showed candidates hiring ballot brokers who lived in the senior communities they would collect from. Many of these brokers, when questioned by the press about payment, would try to deny it despite campaign records showing it. The trick here was that brokers were trusted neighbors – and many voters told the press they trusted the man/woman to pick the right candidate. For the voters, it came off as a convenience.

Just a few days before the runoff, Florida Department of Law Enforcement served a subpoena to Alberto Russi, a 92 year old ballot broker for Suarez. Inside his home, which had seen multiple absentee ballot requests for the first round and all witnessed by him, was 100 absentee ballots set to be turned in for the runoff and 21 voter registration cards. Russi was like many ballot brokers, folks trying to get influence with city hall for things their worn-down communities needed. Russi, a Cuban exile, was not rich. He lived in a modest house with bars on its windows. Politicians like Suarez and Commissioner Humberto Hernandez would remember these loyal people. In the interview with Russi, he talks about helping Commissioner Hernandez’s secretary register at his neighbor’s house so that she could vote for her boss in the November 4th election. His next lines stand out – “This is illegal?” – or “I hope she doesn’t get in trouble. She is a nice girl and wanted to help out.” The point I’m making here is Russi isn’t some mastermind villain.

Now, why am I talking about Russi? He was a mentor of Commissioner Hernandez – who had been elected in a 1996 special election. Hernandez, the son of a Bay of Pigs veteran, was a young and charismatic Cuban politician who had already been suspended from office for money laundering and bank fraud. His 1996 win was the last year of Miami holding at-large elections. His win against Richard Dunn meant no Black commissioners remained in Miami, a first in 35 years. The ethnic split in the vote (which saw Dunn dominate the black and white vote and Hernandez dominate the Hispanic vote), coupled with Hernandez’s already poor reputation for ethics, resulted in the final move to single-member districts – which were set for the 1997 elections. Hernandez ran for the newly-created district that covered the 80%+ Hispanic “Little Havana” and got 65% of the vote in the November 4th election.

Hernandez, who hated Carollo for backing Dunn in the 1996 election, endorsed Suarez for the runoff. His and Suarez’s machines worked in tandem in the Little Havana region of the city and across the exile community. This drastically improved Suarez’s share of the Hispanic vote in the runoff. While the absentee investigation was already raging by the runoff, there was a similar share of ballots returned compared to the first round and they again dominated for Suarez. Hernandez would be a staunch Suarez ally on the council. However, he’d eventually be suspended from office again and serve jail time for his corruption scandals.

Election Thrown Out!

Even as Suarez was sworn into office, the investigation into the absentee fraud continued. In March of 1998, the circuit court THEW OUT the first round of voting, saying the absentee fraud was so severe it could not stand. There was no way to parse out which ballots were legitimate our fraud. The only choice was to disregard it entirely.

Just a few days later, the appeals court of Florida restored Carollo as Mayor, arguing he would have won the first round of voting if not for the fraud. No new election was ordered, instead the court found that under any fraud-free absentee vote, Carollo was so close to 50% that he would have achieved a majority. In the final eyes of the court, no runoff should have even taken place. Carollo was officially elected on the 1st round of voting and restored to the office of Mayor on March 12th, 1998.

Did the Runoff Secure Name-Change Victory?

As I’ve laid out, the runoff was the key driver of turnout for Miami. There is no reason, based on the data we have, to believe turnout in the city would have remained high for just a name-change county referendum. The question is, would turnout have dropped enough to cost YES the victory?

One tricky issue is we don’t know how the absentees voted within the city, so there is at least a batch of absentees we cannot factor in. That said, we can still run some math to get an idea of what different turnout dynamics would have meant.

The YES side of the referendum won by 3,400 ballots.

In Miami, 30,000 ballots for the referendum were cast on election day

From that block, the YES campaign netted 5,400

For YES to still win countywide, they needed to net 2,100 ballots out of Miami

Assuming the 59%-41% margin does not change….

If turnout fell to 10% or lower in Miami, the same range as the rest of the county, then the referendum would fail by over 800 ballots

If a runoff was not taking place in Miami, there is little reason to assume turnout doesn’t collapse. A drop of 50% would put the measure at risk, and only a 50% drop seems generous. More likely 60% to 70% of the city voters would have stayed home on November 13th. Without that runoff, the referendum likely fails. This cannot be said for sure due to the black box of absentee data, but its a reasonable bet if you had to make it. Its more likely to have failed to have succeeded; even if not a guarantee.

We will never know for sure how the vote would have gone without that runoff election in Miami. Too me, however, it is quiet humorous that Miami finally got its name added to the county title due to one of the biggest fraud scandals in recent memory.

Honestly, Miami would have it no other way.

Real ones remember when you wrote an article about this issue resulting in a court deciding to strike down the name change referendum as illegitimate for April Fools once.