Issue #187: The 25 Year Fight for Gay Rights in Miami-Dade County

The fight for equality from 1977 to 2002

Today marks the last day of Pride Months for 2024. On each day on Twitter (screw you Elon), I have been posting #MappingPride, posting one map a day that revolves around LGBT rights or LGBT candidates. The cap off the month, I wanted to write about the fight for gay rights in Miami-Dade County. A fight that went from 1977 and into the 20th century.

Much had been written about the gay rights movement in Miami-Dade. For decades the community built a home in the area. The infamous 1977 referendum and Anita Bryant looms large. However, the fight in the late 1990s and early 2000s is often overlooked. With that in mind, I want to give more attention to the 1990s and 2000s fight. First, however, I’ll touch on the events from 1977.

The 1977 Ordinance and “Save Our Children”

The story of Dade County’s 1977 gay rights ordinance, the emergence of Anita Bryant as an anti-gay crusader, and the repeal vote, is well documented. I only want to summarize events here. The saga of 1977 deserves its own article, and I would like to do a much deeper dive down the line.

The gay community and Dade County have a long history. The Miami and Miami Beach communities were especially known as a destination for gay men and women. As the gay rights movement pushed through the 1970s, Dade Commissioner Ruth Shack proposed an ordinance that would protect gay men and women from discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodation. Despite protest, the measure passed 5-3 in January of 1977.

After passage, the “Save our Children” organization formed to push for repeal. Anita Bryant, a born-again Christian singer who was then spokesperson for the Florida Citrus Commission, became the public face of the effort. Through the campaign, which would see a June vote on the ordinance, the gay community was constantly villified. By Bryant’s own account, those who recruited her to oppose the ordiance played up the myth of LGBT people being more predatory. Bryant’s opposition to gay people being teachers drove much of her opposition.

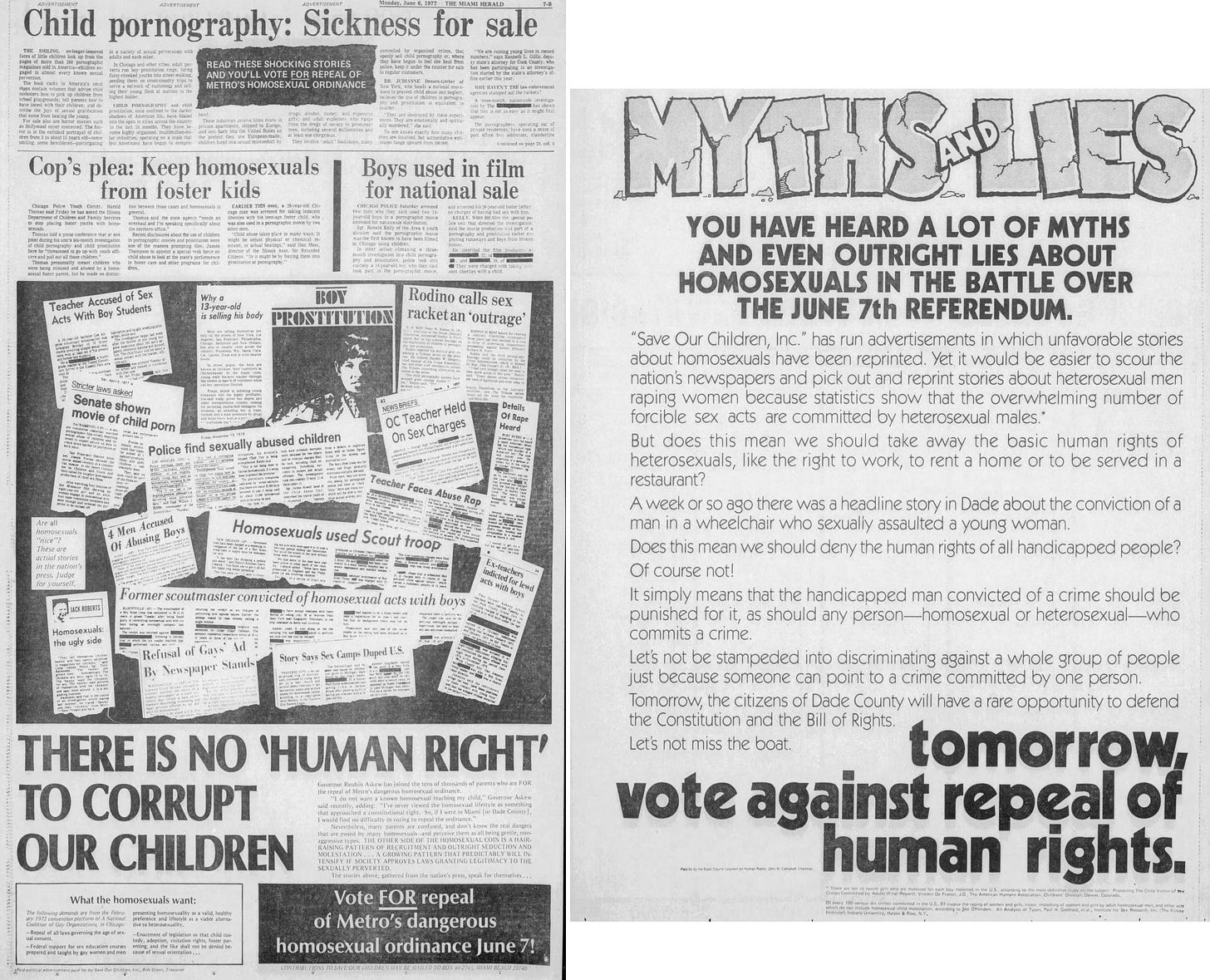

During the election, the “Save or Children” campaign ran ads selecting horrible accounts of abuse, and aiming to paint the entire LGBT community as dangers to children. The anti-repeal forces pointed out this hypocracy and selective reporting. By this point, ample medical and psycholigal studies had dispellened any link between sexuality and predatory behavior, but the public largely bought into these tactics.

The Save our Children was a far more organized effort. A very thorough look at the campaign can be seen here. In the end, the repeal easily passed by a 2-1 margin. The repeal vote was a major blow to moral among the gay community.

What is often forgotten is that another vote took place in 1978. Gay rights leaders pushed for a new ordinance, this one expanded to other issues like religious protections, that would appear on the November ballot that year. This measure would fail, but by a much closer margin amid higher turnout.

The result of the 1978 campaign saw the gay community disappointed, but also happy about the shift in margin. It certainly pointed to the 2-1 repeal in 1977 being driven by turnout and perhaps some changing minds. While talk of another vote for 1980 came up, no new ballot measure would be pushed for the next decade. Focuses in the 1980s moved to the AID epidemic and other battles for rights on the national level.

Bryant, meanwhile, won that fight but lost the war. The controversy she generated led to her - as conservatives would say - being “cancelled.” Her contract with the Citrus Commission was not renewed in 1980 and she lost many paid gigs thanks to protests and different venues and groups not wanting to suffer blowback. Bryant divorced her abusive husband in 1980; but that divorce drove a wedge between her and the evangelical community. She’d eventually retreat from public life.

The 1998 Ordinance Fight

Gay rights would be voted on and debated across different counties, cities, and states through the 1980s and 1990s. Dade County would finally have a debate over the issue beginning in 1997. That year, Commissioner Bruce Kaplan introduced an ordinance similar to the 1977 proposal; banning discrimination based on sexual orientation for housing, employment, and public accommodation. In the 1990s, an organization called SAVE DADE was formed to advocate for the LGBT community.

The 1997 effort, however, stalled in June. On the 18th of that month, the commission voted 5-7 against moving the proposal forward for another reading. The reaction to the proposal had led to a massive religious drive to kill the effort. Not all of the 7 were firm in their opposition to gay rights. Dennis Moss, a black commissioner representing southern Dade, vote not to move forward because as he saw it, the measure was not needed. Commissioner Pedro Reboredo, a Cuban Catholic, directly sited his religious objection.

Organizers did not give up however, heading into 1998 looking to find the votes on a repeal. In October of 1998, it was believed at least six commissioners out of 13 were on board. The issue was so divided, that conservative groups tried to force pro-gay commissioner Jimmy Morales to recuse himself due to possible conflicts regarding his law firm. They argued Morales’ firm could benefit from any future discrimination suits done under the ordinance. This effort led to nothing when ethics officials confirm Morales had no conflict.

In late October, SAVE DADE and the Catholic Archdioceses announced an agreement. The proposed ordinance would exempt churches and church-run programs, and in exchange the Church would not oppose the measure. In November, public meetings were held on the ordinance. This proved crucial in swinging over at least one member. The virtriol on display did not help the opposition.

“Homosexuality is choice. Its a demon. Its a sin” - Patricia Millien, giving a well-structured legal argument in opposition.

“I have nothing against the homosexuals. What they do behind closed doors is their own business. But I don’t think I should be obligated to participate in their things or mingle with them" - Businessman Carlos Dominguez, apparently worried if he lets a gay person work at his store it will be like sex or something

The responses from supporters fed off of the nasty attacks.

“If you need proof of why we need this ordinance, you heard it here tonight” - Heddy Pena

Organizers kept working to win over votes as needed. The vote was finally scheduled for December 1st, 1998. In a narrow vote, just 7-6, the ordinance passed!

The YES votes came from areas that even today still lean Democratic. Four of the five NO votes were from more conservative Hispanic Commissioners. Dorrine Rolle, a black commissioner recently appointed to district 2, was a surprise NO. Meanwhile, Dennis Moss, who’d voted NO back in 1997, switched after he said the hearings showed him the measure was a well-balanced proposal to combat the discrimination he saw. Notable names on the YES column also include longtime Cuban Republican leader Bruno Barreiro and former State Senate President Gwen Margolis.

The opposition was absolutely despondent. They vowed recall efforts against commissioners, which amounted to nothing, and vowed a repeal effort. Over the next few years, no commissioners would see their electoral fortunes fade due to the vote.

Repeal Effort Struggles

Opponents of the ordinance were unable to mount the rapid-fire petition and referendum drive that the 1977 efforts had achieved. Opponents, largely organized under “Take Back Miami-Dade,” would need to gather over 35,000 petitions, or 4% of the county’s population, to get it on the ballot. This effort began in 1999, but eventually failed to gather the petitions needed. It came as commissioners who opposed the ordinance, like Miguel Diaz de la Portilla, argued that revisiting the issue would prove to be divisive and unnecessary. In the end, the effort failed when it only gather 27,000 petitions by the summer of 2000.

Not to be deterred, the opposition again rallied to gather petitions for the repeal, launching an effort in September of 2000. On December 1st, they submitted over 50,000 petitions. However, the approval dragged on for ONE YEAR. This stemmed from many petitions being shown to be incorrect or incomplete, leading to further review and verification. On top of this, a criminal investigation opened up into fraud in the petition process. The long saga of that is its own story, but it eventually led to Jeb Bush removing Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Rundle from the investigation; with the argument being her support for gay rights was a ‘conflict.’ However, the special prosecutor appointed then brought charges against petition collectors in the summer of 2002; with testimony showing people listed as having signed the petition had not… in fact…. signed the petition. This led to this line by the attorney for the charged individuals.

This is the work of the homosexual, bisexual, and transsexual mafia that wants to destroy our families and take away the right of every Dade county citizen to vote” - Attorney Rosa Armesto de Gonzalez

This is not exactly the quote from someone who thinks their client has the facts on their side.. While that legal saga would drag out through 2002, in December of 2001, the Miami-Dade elections department was able to verify the petitions needed for the ballot had been achieved. This meant the measure would be on the September 2002 ballot, the same day as the state primary.

The 2002 Campaign

The referendum held in 2002 would be over whether or not to repeal the ordinance from 1998. A YES vote was to repeal (anti-equality) while a NO vote was to keep things as is (pro-equality).

The supporters of the law formed the ‘Say No to Discriminations’ /Save Dade Committee. The coalition included a vast array of political and business leaders. Even before the campaign was set, leaders like County Mayor Alex Panelas outright urged the measure to be dropped; warning of the divisive nature a referendum would bring.

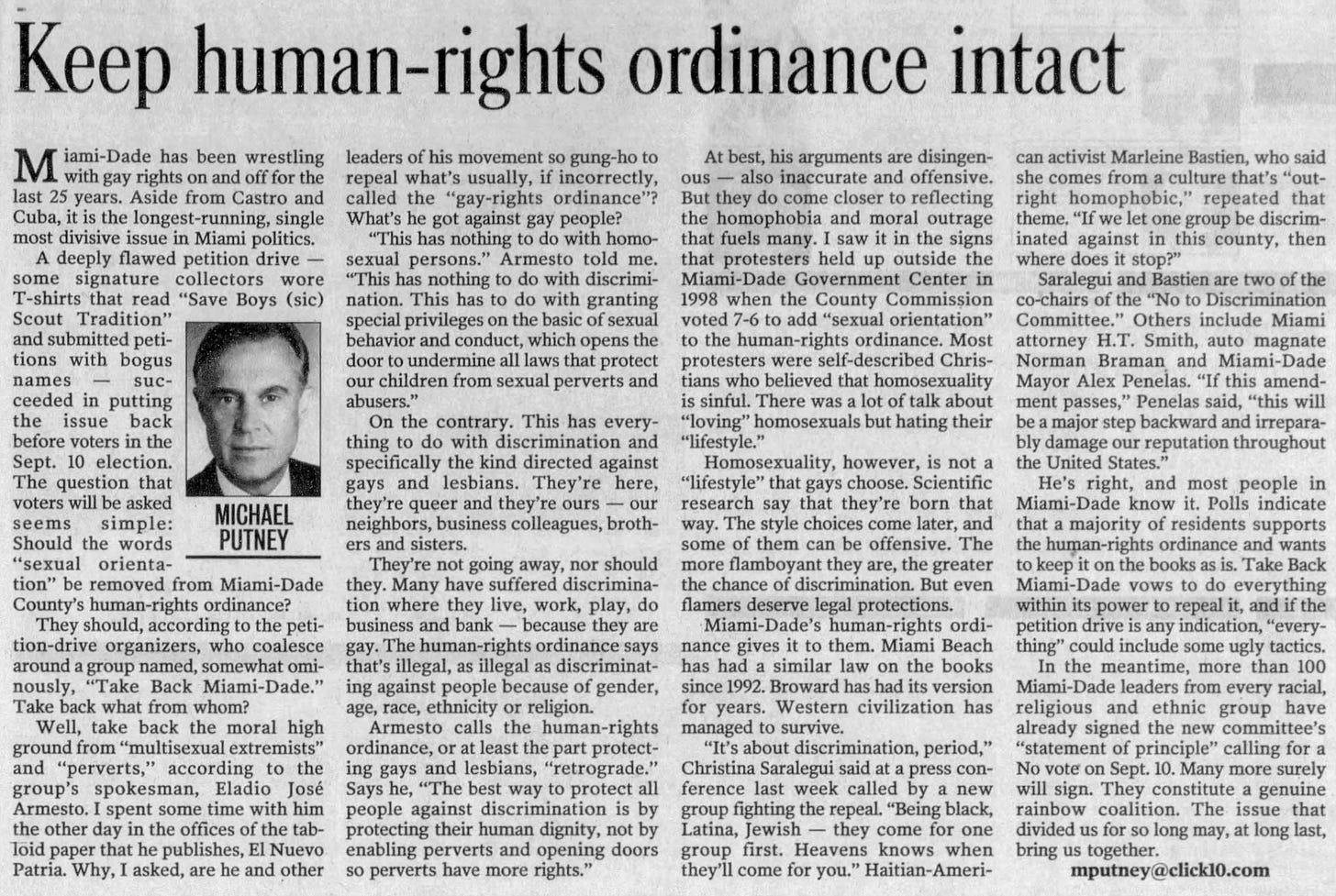

Through the spring and summer of 2002, the organizations for and against the repeal organized their efforts. Religious leaders were the main force of the “Take Back Miami-Dade” effort. However, they ran against the diverse coalition of backers of the ordinance. Business leaders warned that repealing the ordinance would damage the area’s reputation for tourism and other business communities. Religious and racial leaders from all groups organized to outreach to their communities. The papers also remained firmly against the repeal effort.

Major battles took place within the Hispanic and Black communities over the issue. In the Black community, several reverends argued against the proposal. However, major Black leaders like Carrie Meek, and the NAACP itself, encouraged voters to reject the repeal efforts. In the Hispanic community, the large Catholic presence was the major obstacle; however, several LGBT Cuban volunteers worked to swing voters. Mayor Alex Paneles, himself a Cuban Democrat, was a major surrogate in this effort. I don’t have the final vote by race, but I do have the registration for that time.

Polls heading into the election showed every major demographic was against the repeal effort. White voters were the most anti-repeal; a not especially surprising statistic considering Dade white voters were much more liberal than the rest of the state; owing partly due to large LGBT and Jewish populations; with white conservatives long left the county by this point. Black and Hispanic voters were more divided, but leaned against repeal. Among Hispanic, the more Catholic Cuban population was less sure.

The results were overall good for the anti-repeal forces. The NO side was already over 50%. The concern among the anti-repeal forces was if the undecided’s were “shy yes” or if turnout could throw off the data. In a clear sign, however, that the YES campaign was not optimistic, they accused the county of planning “massive fraud” to ensure repeal failed.

Hey look, we found out the people that gave Donald Trump his campaign strategy.

The election finally came on September 10th. Turnout in the county was 32%, with 290,000 ballots being counted. Turnout was especially high among Democrats, 37%, compared to Republican’s 29%. This was no doubt helped by the Democratic primary for Governor featuring the county’s own Janet Reno. In all, the vote cast broke down 53% Democratic, 35% Republican, and 12% independent.

As Janet Reno secured 70% in the Democratic primary for Governor in her home county, and a slew of other candidates fought it out for legislative and commission seats, all eyes turned to the gay rights repeal vote.

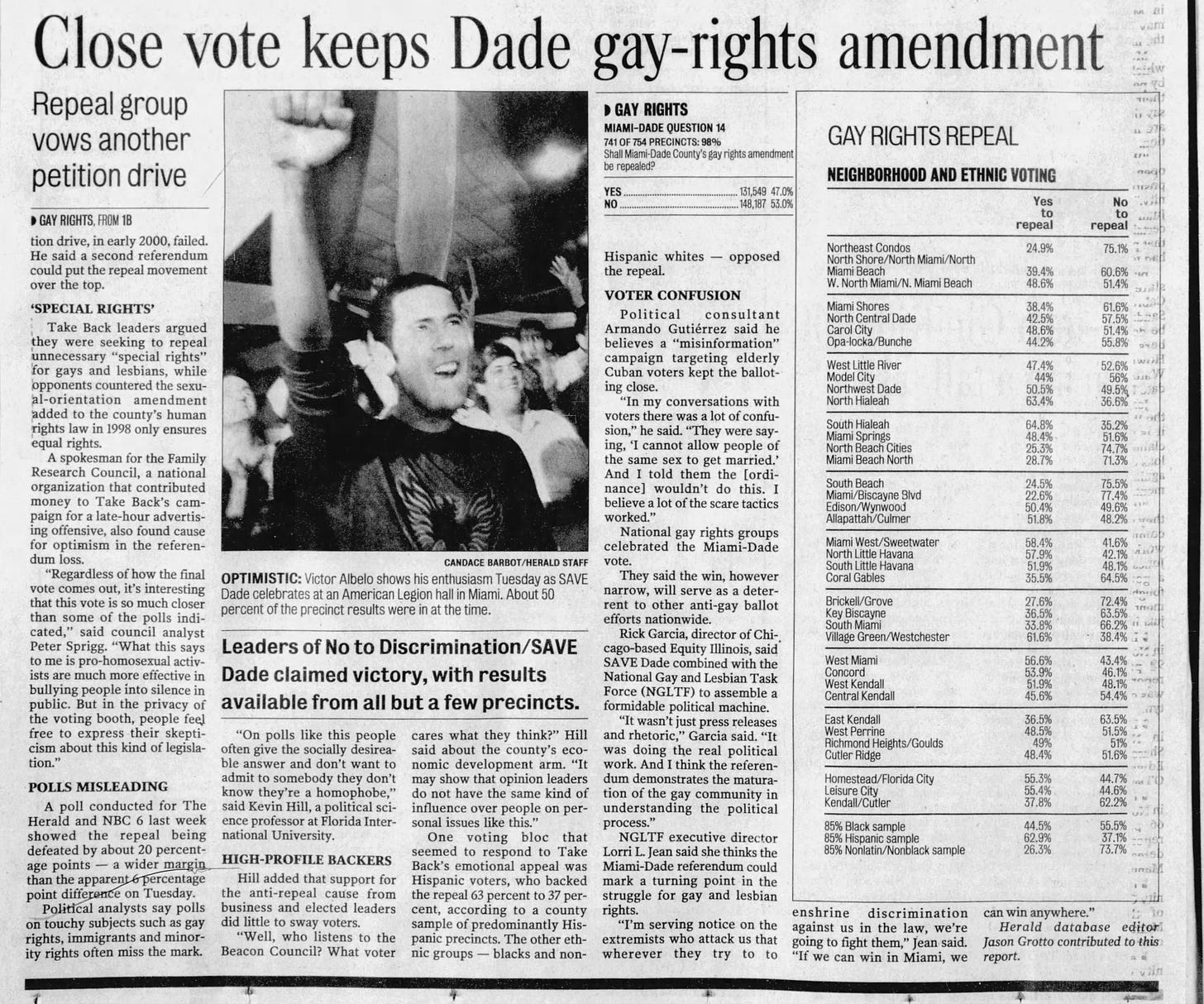

The vote was the subject of national coverage by the end of the campaign. With 53% voting NO on the repeal, the effort from conservatives failed by just under 20,000 votes!

The pro-repeal crowd was despondent and vowed to launch another effort, which never happened. Many anti-repeal leaders were surprised by the close result, however, as polls showed the NO forces in a much stronger position. Some did wonder about confusion either in the poll wording or ballot wording. On top of this, apparently a disinformation campaign went heavily into the Cuban community to imply the measure was about gay marriage.

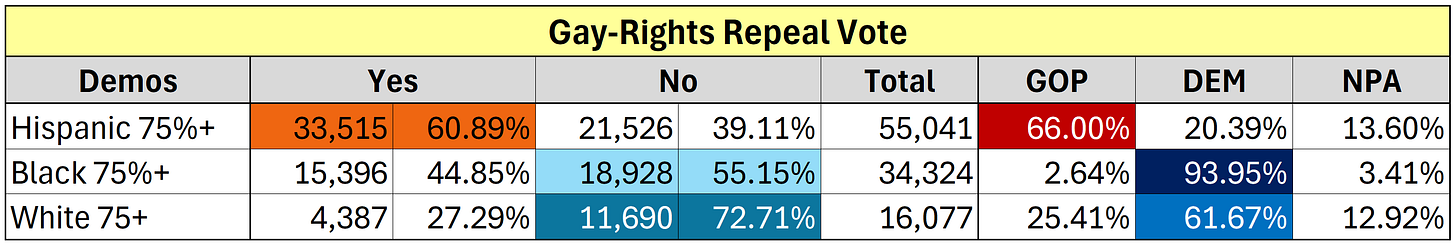

The Herald also has some notable demographic and regional data. Their demographic report is similar to what I see, albeit I used a wider precinct sample. White and Black voters rejected repeal, while Hispanic voters backed it. However, I do see that in those Hispanic precincts, the Republican share of the electorate was VERY high.

Primary elections mainly draw hardened partisans to the polls; even in times when a local measure like the repeal effort would bring out more unaffiliated/NPA voters. Therefor, with the Hispanic precincts so heavily Republican, its easy to see that margin. Black voters, meanwhile, broke 10 points against repeal; a major gay-rights victory for a community with a strong religious presence. The precincts I looked at showed most were between 40% and 60% on repeal.

Regardless of margins, the result was a major victory for the gay rights movement. Another referendum would never come. Then, in 2014, the commission would expand the ordinance to include gender identity in a 8-3 vote. Despite referendum threats from opponents, no effort succeeded.

Today, the fight for LGBT rights and equality continues. The same forces that threw out fear mongering in the 1970s play the same game today. They have nothing but fear and bigotry to fuel them. However, as the saga of Miami-Dade shows, in the end, the eventually lose. Time is against them.

And yes, in fact, the gay mafia is real.