Issue #161: The History of Ireland Ballot Measures & Why The 2024 Proposals Lost

Shifting social politics in Catholic Ireland

On March 8th, voters in Ireland went to the polls to cast ballots on two proposed constitutional amendments. It was the latest series of votes in recent years that has seen the nation update its conservative 1937 constitution. In the modern era, Ireland’s population has become more progressive on many social issues; with many of the old bans, from abortion to divorce, being repealed.

These referendums both started off very uncontroversial. They largely aimed to reword language around family and amend to strip out language that said a woman belonged in the home. Both started off with dominant polling leads. However, as the campaign went on and the government struggled to articulate the changes, why they were needed, and the effect of the proposed new wording, voters rejected both.

These rejections were celebrated in far-right twitter as some sort of proof that conservativism was back in Ireland. Serious analysists all agree that is not the case, but rather a stunning example of the government’s botched campaign and the poor wording of the measures. In league with this, I wanted to discuss those measures, but first I want to take a look at the march to this moment. I want to look at some of Ireland’s most notable referendums, and how they show the nation’s transition from religious conservativism to a more egalitarian/secular government.

The Conservative Years

As stated before, Ireland’s constitution came from a very conservative era. The constitution used today was drafted for the Irish Free State in the mid 1930s. Eamon de Valera, a prominent Irish political leader who was part of the founding of the Fianna Fail party, drove the move to draft a constitution that would replace the 1922 one pushed from the Irish-Anglo treaty. John Hearne, an academic and advisor to the government, is considered the main drafter and the “Thomas Jefferson of Ireland.” The constitution drafted and presented saw input from major religious figures, with a copy even sent to the Vatican for their take. The Vatican opted to not offer an opinion, but there was a clear religious hand in the drafting, which no doubts reflects the deeply Catholic nature of the nation.

In a 1937 referendum, the constitution was approved. Since then, it has undergone many amendments. Many of them revolve around government structure, treaties around things like the EU, and other non-social matters. However, social issue amendment votes highlighted the socially conservative bent of the electorate.

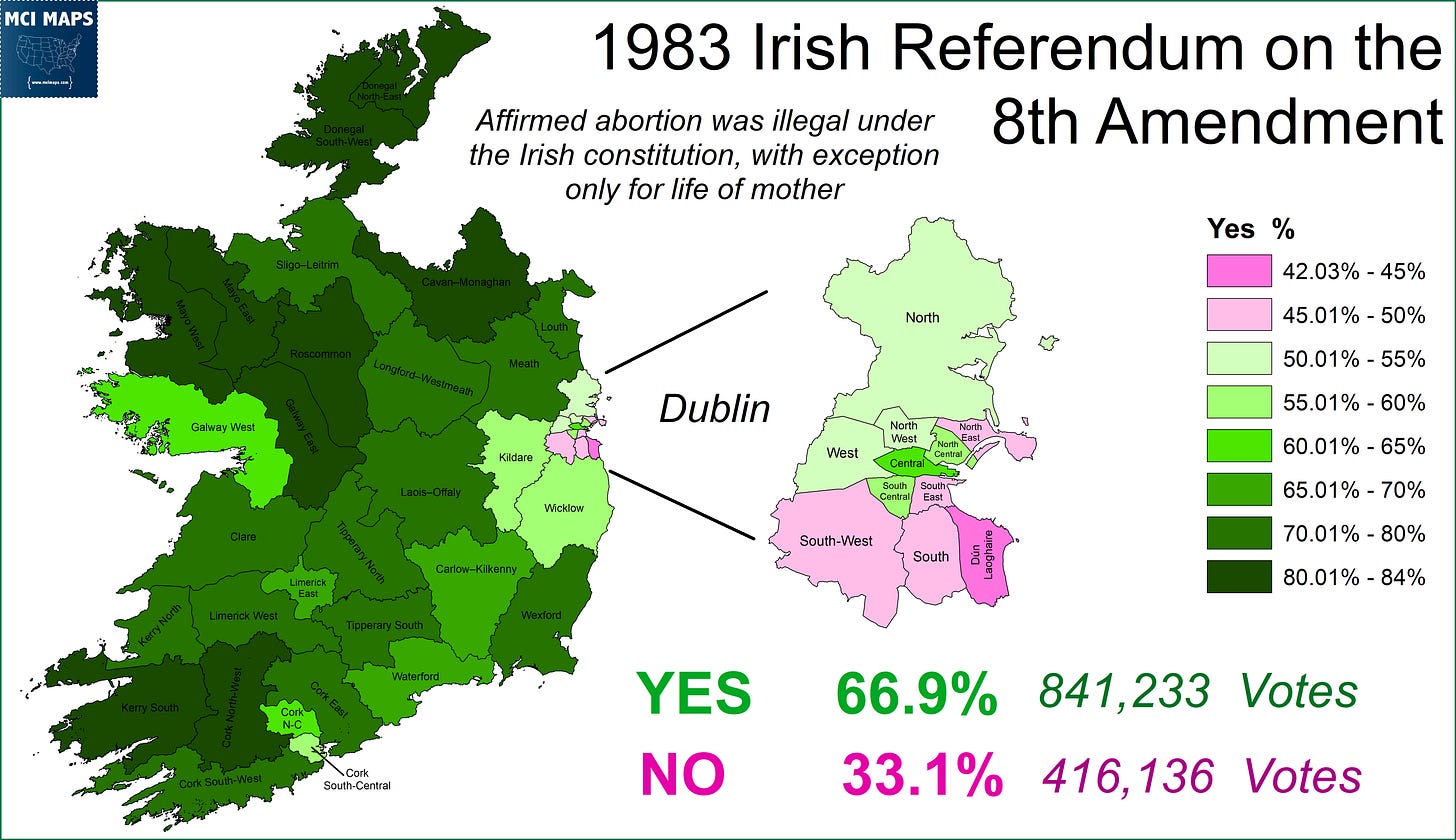

In 1983, Irish voters went to the polls to vote on the 8th amendment; which would add the ban on abortion to the constitution. While abortion had been illegal in the country since the 1800s, recent court rulings made anti-abortion leaders worried the law would be struck down. The constitutional amendment kept abortion banned and left only the life of the mother as a legal reason to get the procedure.

The measure would easily pass everywhere outside of Dublin, with only a few of the city’s constituencies rejecting the measure. This will be a common site in these campaigns, with Dublin being easily the most progressive part of the country.

A few years later, voters were asked to weigh in on the issue of divorce. The Irish constitution banned divorce, but by the 1980s, the issue of unhappy marriages and people just living apart due to the law led to a Government committee to look at possibly loosening the restriction. The issue was put before the voters, with Fine Gael backing it but Fianna Fail opposing it. The Catholic Church also opposed it. The amendment went down to defeat.

The failure of the divorce amendment highlighted again how socially conservative the population was; as well as the influence of the Catholic Church.

In 1992, Irish voters had three measures related to abortion to vote on. These came after the “X Case” - a landmark Supreme Court decision in the nation. The case revolved around an un-identified minor (X) who’d become pregnant via statutory rape and was suicidal about her lack of options. The court ruled suicidal risk was part of the “life of mother” exception.

Fianna Fail, keeping with their conservative leanings, pushed the proposed 12th amendment, which would have removed the suicide exception, thus overriding the court. This measure was seen as too extremes, and failed massively, not evening winning the most conservative areas. The map is on my twitter (size limits here).

Also stemming from the X case was issues around traveling for an abortion or providing information on abortion services. The 13th amendment, which passed the same day the 12th failed, affirmed that citizens had a right to travel out of the country to get an abortion. While Ireland didn’t want abortion in its land, it was not intent on prosecution for out-of-country activities.

There are many Republican politicians in American today who want to track if women get abortion’s outside of their state. They are officially behind Ireland 30 years ago.

The 15th amendment, passed the same day, affirmed that people had a right to provide information on abortion options. This stemmed from several cases, including those of college student unions providing information for travel for an abortion.

These measures were seen broadly as compromises on the issue; with abortion remained banned for over two more decades.

In 1995, voters went to the polls again on the issue of divorce. The ruling government again put a measure before the voters, as the issue of informal separations continued to rise. The campaign was very intense, with the Catholic Church strongly encouraging a NO vote. However, the Church did affirm Catholics could vote YES and still be in good standing. The ruling Fine Gail government actually spent funds on the YES side, something that generated plenty of controversy. The measure would end up passing by the narrowest of margins.

The proposal had initially earned broader support, but the polling tightened as the campaign came to an end. The passage meant courts could allow divorces based on strict criteria. This was hardly no-fault divorce, but was a first step.

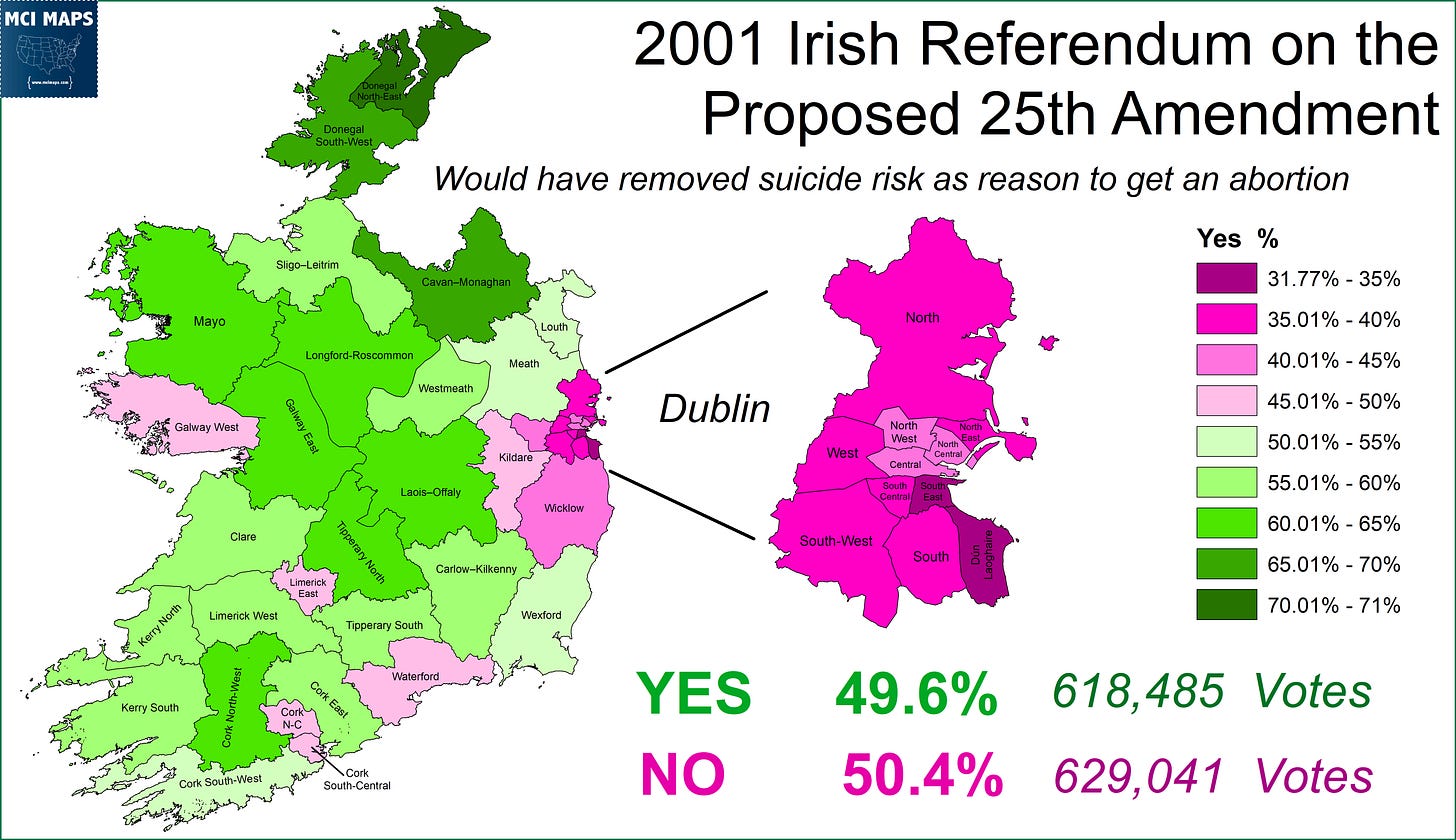

Finally, 2001 arguable saw the last major conservative vote. The then-ruling Fianna Fail Government proposed another shot at removing suicide as a risk factor for allowing an abortion. This proposal was very contentious and split the legislature, with the Fine Gail opposition against it. Despite its easy loss in the 1990s, this proposal almost passed, failing largely due to Dublin.

I am not expert on this time, but I’d venture the close vote was due to the X case being so far in the background. The Catholic Church and conservative groups backed this measure, with arguments that suicidal risk was being abused as a reason and with the right to travel already in place. After this loss, though, the exemption would not be put before the voters again.

After this period, ballot measures on social issues would die down for the rest of the 2000s. However, when the 2010s came around, a notable shift in voter sentiment emerged.

The Progressive Shift

The first big social issue referendum in many years came to Ireland in 2015. That year, as other nations were engaging in debate around the legalization of same-sex marriage, the government put the issue before the voters.

Unlike previous amendments, which had divided along differing party lines and saw intense debate, the gay marriage proposal had a broad YES coalition. All major parties backed the proposal, as major business groups. Unlike past measures, the Catholic church formally stayed out of the debate. Some Priests and Church officials would offer YES or NO sentiments, but the formal church hierarchy stayed out of things. The Church of Ireland stayed neutral as well. The most vocal no groups were Presbyterian and Methodist churches, but these were small groups in Ireland.

The Catholic Church by this point likely knew it had to stay out of the matter. The church’s influence in Irish culture was diminishing, especially aided by the massive Priest sex scandals. While a vast majority of residents viewed themselves as Catholic, Church attendance was dropping. In 1991, 79% of Catholics said they attended Church Weekly. By 2011, it was around 45%.

The YES campaign also ran a smart strategy, focusing on the communal nature of the vote and how it was about all citizens affirming their support for their LGBT neighbors. This ad from the YES side is a brilliant and touching piece.

I covered the Irish referendum back in 2015, and wrote a detailed breakdown of the vote. You can read much more analysis in that.

Ireland 2015 Same-Sex Marriage Vote Article

The results seemed to never be in doubt, with the YES side constantly leading in the polls. The worry of a “shy NO” vote never came to fruition.

The win, and especially the monumental margin, made Ireland the first nation in history to legalize Same-Sex Marriage by the ballot box.

Three years later, Ireland voters would take on the issue of abortion once again. Several governments had recognized the issue with the strict ban, as abortion via medication, or underground procedures, or the financial burden of travel, all complicated the state’s position. After several years of government committee studies, the legislature voted to put a measure before the voters that would repeal the ban and instead give the government the power to regulate. The government then released a White Paper that laid out several broad policy positions for a proposed law. Abortion would be legal up to 12 weeks, and then requiring different levels of approval after that. Mental health would be added to physical health concerns and fetal conditions would also be a factor. This would still be a restricted right, but future changes could be made via legislation.

No major national party supported a NO vote. Greens, Labour, and Sinn Fein all backed it, while Fine Gail and Fianna Fail remained neutral. However, most FG legislators backed the YES side, while many FF backed NO. The repeal of the ban easily passed, taking well over 60% of the vote.

This was viewed as another major moment in the shifting politics of Ireland. Like with the Same-Sex marriage vote, the Catholic Church, and really most religious groups, stayed neutral on the proposal.

Then, later that same year, Ireland voted on a religious issue! Recently, the county’s old ban on blasphemy had taken center stage when comedian Stephen Fry had been investigated for breaking that law. As a result, the government opted to put the issue of repealing the ban to the voters in October, the same day as the Presidential Election. The measure would easily pass with 65%.

Major religious groups did not aim to defend the law, which most regarded as obsolete and embarrassing. The fact that such a ban was in the constitution should really highlight the era it was written in.

The Botched 2024 Referendums

Over the last few years, the Irish government has continued to look at needed updates to the laws or constitution of the nation. Plans for referendums to update language around gender and the family were planned for 2023, but moved to March of this year. After a good deal of drafts, it was settled that Irish voters would have two amendments to vote on

39th Amendment: Which amend language around family to include “whether founded on marriage or on other durable relationships”

40th Amendment: Remove the lines from the Constitution that states “In particular, the State recognizes that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved. The State shall, therefore, endeavor to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”

This language would be replaced by broader language on the importance of family broadly, without any gendered language

These measures both started off with high support and little controversy. In essence this was just updating some outdated and sexist language, and expanding some definitions. Unlike the same-sex marriage, divorce, or abortion votes, there was no major case or legal issue at play.

However, even at the time, cracks emerged. Some opposition parties, like Sinn Fein, pointed out the bad wording and concerns, though they did back YES campaigns. Concerns heavily revolved around “other durable relationships” being a vague statement that could be interpreted widely by courts. There were also concerns from disability rights advocates who said the language put too much on families to treat those who needed assistance; possibly absolving the government of responsibility in aid.

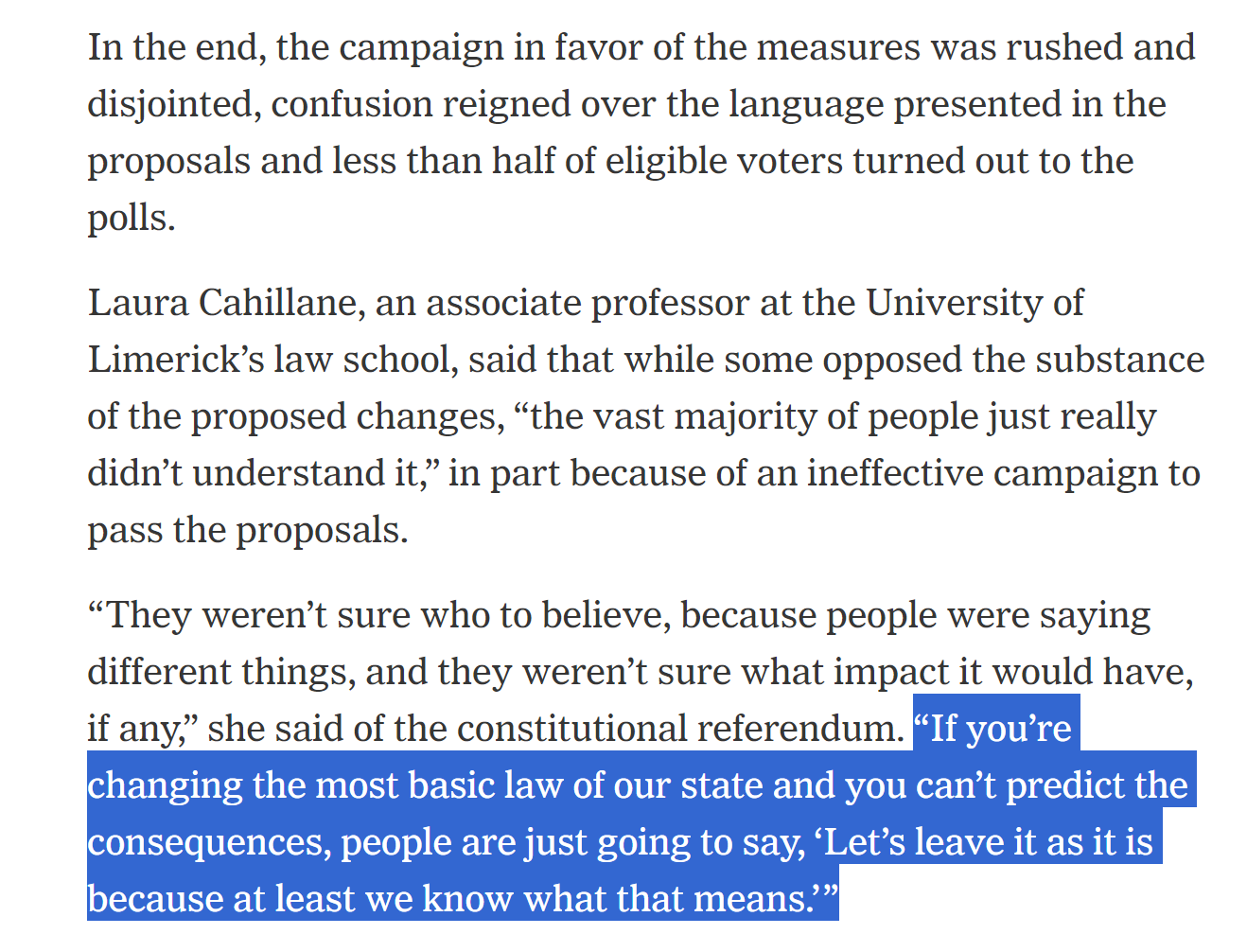

Social conservative opponents to changing the language on women took advantage of growing confusion and a muddled message from the government. The campaign began to see a slide in support as voters continued to debate the effect of the changes and worry about the wording. Good breakdown of the situation here.

The segment from the NYT coverage I think purposely sums up what happened. As the final days of the campaign emerged, which by that point saw many YES groups struggling to assuage concerns as worries also emerged about law turnout.

Indeed, with confusion over the wording continuing, and with the practical effect of the changes largely viewed as cosmetic, voters rejected both proposals by landslide margins. Exit polls showed a wide array of demographic and party supporters opting to reject both measures.

Both measures lost across rural Ireland but in Dublin as well. This I believe really affirms how little of an ideological fight this was. The most hardened left-leaning districts were either narrowly in favor or narrowly against, but this still reflected a lot of left-leaning voters saying “I’m confused about the effects of this and lets stay pat for now.”

There is something in the data that indicates the women’s role amendment would have been closer, as that measure, like the failed US Equal Rights Amendment, generated more iron-clad conservative opposition. That said its hard to imagine a referendum campaign with clearer language and a bad campaign doesn’t pass like past measures.

In the short term, I don’t think another vote will come. The ruling coalition has admitted it misjudged the electoral mood while also not articulating things clear enough. Parties like Sinn Fein have said they’d support another referendum if they are ever in Government and with better language. They were one of the parties highlighting issues around disability aid.

The result is a black-eye for the ruling coalition. To me it does not reflect a conservative attitude from the electorate, but rather is a reflection of a bad campaign and poorly worded language. I do expect down the line to see cracks at changing the language come before voters again, and ideally learning from the mistakes of 2024, clearly-worded measures will easily pass.