Issue #156- How rural Liberty County, FL elected its first Black County Commissioner

A county with a long history of racial repression

Today’s newsletter was actually written last year. This article, covering racial representation in rural white Liberty County, FL, was originally posted to my $5 Patreon Tier in July of 2023. I wanted to open it up to all readers as part of my series of articles on African-American electoral history and representation. I’ve made some edits and added some more information as well. Here I cover the story of racial suppression in Liberty County and the eventual election of its first black county commissioner.

Enjoy the reading! If you want to read more racial politics history, I just published a Patreon piece looking at Shirley Chisholm’s 1972 Democratic Presidential Primary bid - specifically in the Florida Primary.

Onto Liberty

Rural Liberty County

Located in the panhandle, just to the west of Tallahassee, Liberty is the second lowest populated county in the state. It also has the lowest population density in the entire state; with 2/3 of its land being national forests. The population is largely clustered along major roads. It is heavily white, with African-American voters largely clustered around the western edge, especially in the county seat of Bristol.

The county has long fit in with rural, white Florida; being very conservatives and part of the old Jim Crow South. Like the rest of the panhandle, it was heavily registered Democrat, well over 95% in fact until the 2000s. However, these white democrats would often vote Republican for major federal races. However, Republicans have only begun to actively contest local races very recently. The voter registration only flipped to the GOP last year.

For much of its history, like much of the deep south, the black population of the county was heavily repressed. The county used to be closer to 40% black, but much of that population fled during the 1920s Great Migration. Those who remained were not allowed to take part in local politics; which was in the control of a handful of prominent white families.

An effort by black residents to register to vote in 1954 led to a wave of violence and cross burnings. When asked in the press about the wave of violence, the local sheriff blew off the concerns as not a major issue. The implication was clear, engage in politics and risk death - and don't expect law enforcement to help you.

"Somebody just fired a few shots in the air in front of one house and a couple of crosses were burned..... There isn't too much to that" - Liberty Sheriff S.G. Revell

It would not be until the 1965 Voting Rights Act that black residents were able to register in force. The effect of this law is clear when the county went from 0 black voters to 177 in just two years.

This is covered even more so in my Voting Rights Act in Florida article.

Post-1965 may have seen black voters able to cast ballots, but the county remained heavily white and very racially polarized. Black voters in the county would come to reliably support racial progressives, but their voice was consistently outpaced by white residents that backed conservative democrats.

A good example of this polarization is the 1972 Democratic Primary for President. George Wallace would get 80% of the vote in Liberty, but the black voters would give over 99% of their ballots to Congresswoman Shirley Chisolm, the first major black candidate for the Democratic nomination and the first black congresswoman in history.

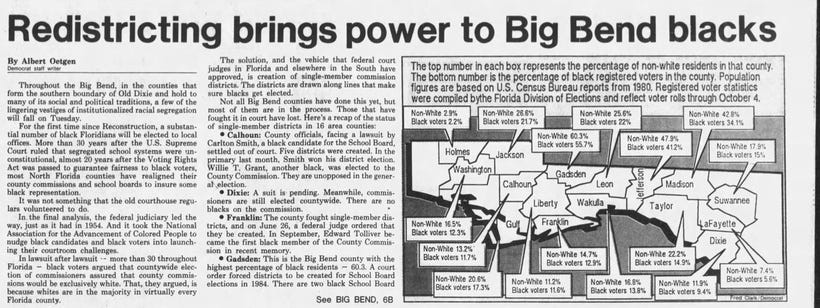

After Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1982, which expanded the VRA to redistricting matters, the NAACP began to launch many successful lawsuits in North Florida that led to many county commissions create single-member districts. These suits were largely successful in the rural counties, including urbanizing Leon County; where it was shown at the time that black candidates were never able to secure enough white backing to win positions in local government.

By 1986, several panhandle counties had been mandated to draw single-member districts.

Back in Liberty County, black candidates would run for office beginning in 1968, none would win office through the 1980s. All races at the time were held at-large.

This eventually sparked a lawsuit to try and force Liberty County to move to single-member districts.

Election data analyzed as part of the lawsuit showed that in 5/6 races where a black candidate ran for office, they received a vast majority of the black vote, but little of the white vote. You can read a great deal about the politics around local offices in the lawsuit case file.

The lone exception here was Earl Jennings, who unsuccessfully ran for School Board, advancing to a runoff in 1980 but not securing the nomination. Jennings, however, was not unanimously supported by black residents. Jennings, according to testimony, was part of a white slate card backed by some prominent white leaders who aimed to oust a rival politician. Jennings did not have as unified of black support in that race, but had much stronger support with white voters than other black candidates. In a 1984 run, he better united black voters, but then lost ground with whites.

Additional data showed that statewide black candidates had near 100% support from the county's black population. Locally, the slating process, which was critical in a small county where everyone knows everyone, could lead to outliers. Broadly, however, the county was extremely racially polarized.

The lawsuit would go through the courts through the 1980s and 1990s, with different courts going back and forth on if single-member districts should be implemented. In the meantime, a major event happened in 1990, Earl Jennings won a race.

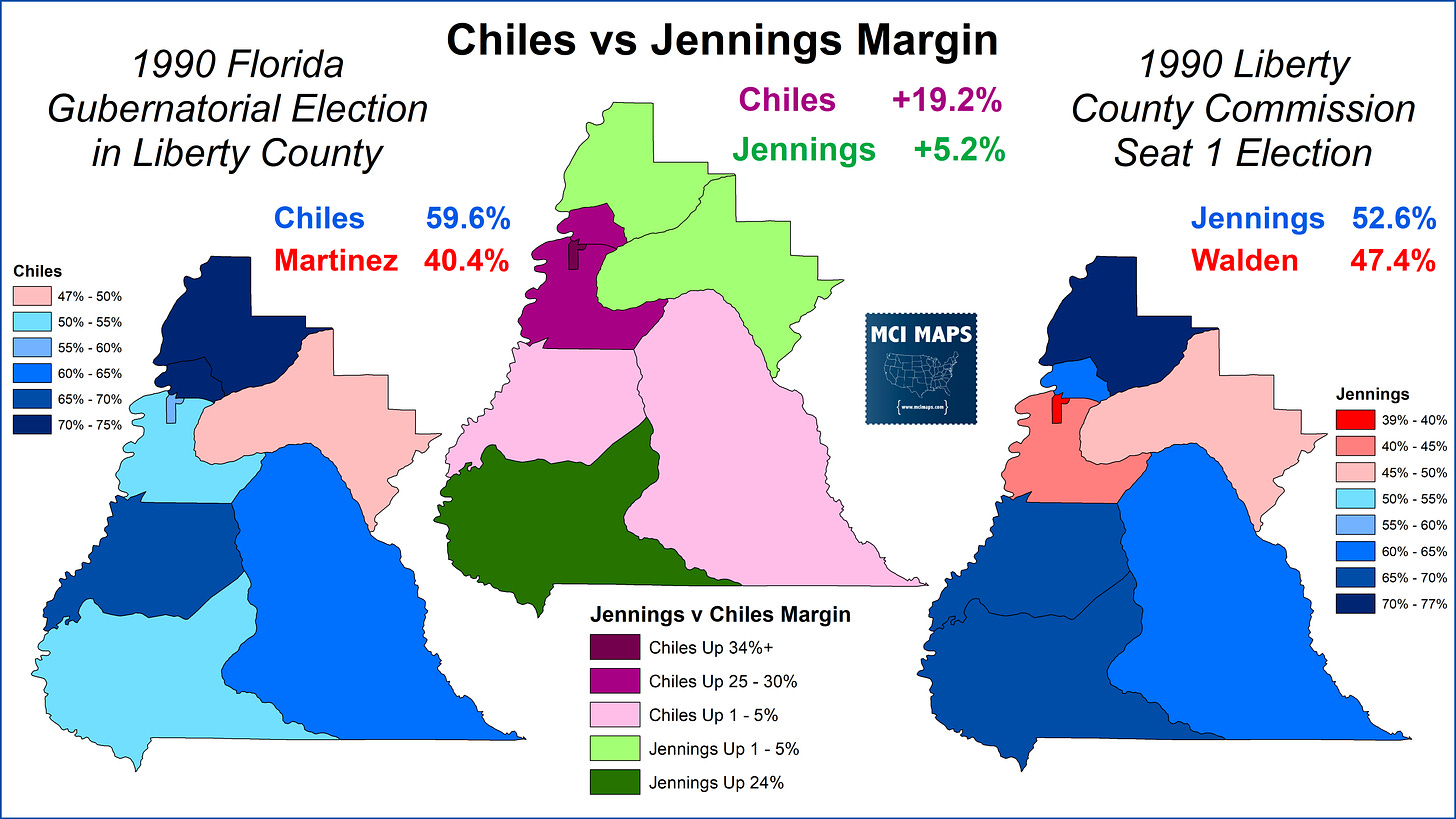

In 1990, the Commission Race for Seat 1 saw Jennings win both a primary and general election. The seat was at the time occupied by Republican Newton Walden, who'd been appointed by Governor Mel Martinez when a vacancy opened up. At this time, no Republican had won local office in the county since reconstruction. Earl Jennings faced off with white Democrat Mary Johnson for the primary. In that contest, he would come out victorious, not only winning big in the heavily-black NW corner of the county, but taking 7/8 precincts. In the general election, he'd defeat Walden by 5%.

Jennings' win came with clear white support, as a victory otherwise would have been impossible. His general election win, however, was much closer than the Governor race that same day, which saw Lawton Chiles beat Martinez by 19 points.

By this point in Liberty’s elections, non-local races saw plenty of ticket splitting. Democrats would still win for statewide contests, but Republicans were beginning to win more and more races.

Jennings would have to run again in 1992, as the 1990 race was a special for the remainder of that commission term. Jennings would be forced into a runoff, but narrowly take a victory that October; winning by 3%, defeating three white democrats. His runoff win came against Willis Brown.

That time, no Republican bothered to file. As the Democratic nominee, Jennings was re-elected unopposed that November.

With the 1992 win, Jennings would not have to run again until 1996. As this was going on, the lawsuit over districting continued. The plaintiffs suing to force single-member districts pointed out that Jennings winning was thanks to his support from key white families that put him on local slates. Those who advocated districts pointed out that the white families would only back minority candidates they felt comfortable with.

The uncomfortable question about whether Jennings won his 1990s races as part of a plot to "short-circuit" the district lawsuit shows up in the court documents. Jennings and the commission fiercely reject this claim, while many of the plaintiffs suing clearly suspected as much. Much debate took place in the court about if Jennings was a mere outlier or if this meant Liberty was not so racially polarized as to make single-member districts a necessity.

In 1996, Jennings would be up for another term, and again faced Democratic primaries. This stood out, however, as Jennings did not win the black vote in the first round. Stafford Dawson and Helen Hall were both black candidates that challenged Jennings for the nomination. Dawson actually won Precinct 1, which was the county's lone majority-black precinct. Jennings would advance, and end up winning a runoff in a 1992 rematch against Willis Brown. Once facing Brown, black voters returned to the Jennings camp.

The 1996 race highlighted notable discontent among many black residents with Jennings.

The Jennings electoral success would be one of several factors that did ultimately lead to Liberty county not securing single-member districts. On top of these races, black unity on the issue was not apparent by this point. Many black residents saw a Jennings-type (someone the white families would support because they weren't especially radical) as the best option in a majority-white and conservative county. Some worried a black commission district would end up with a commissioner ignored by the other 4.

The courts would actually go through several rulings, appeals, and back-and-forths, ultimately ending in at-large remaining the status quo. Liberty County remains at-large to this day. At this point, demographics would not actually allow you to draw a majority-black commission district, so no lawsuit today would succeed.

If a black-majority district could be drawn, there would likely be more of a case for such districts. Today the county backs statewide Republicans with over 75% of the vote, not voting for a statewide Democrat since 2012. In 2020, Liberty broke its long streak and finally elected local Republicans to office.

That year, every Dem vs GOP local race was won by Republicans. In 2022, the GOP ran unopposed, and 2024 will likely be the same. In a countywide contest today, the candidate of choice for the black community is not winning in the at-large system.

Jennings would retire in 2000 and sadly pass away in 2003 from a heart attack. His election, regardless of the issues around slates or family power, was a monumental moment for a county with a very long history of racial violence and suppression. Unfortunately, the modern political of Liberty County mean the elections of the 1990s are not going to be repeated anytime in the near future.

But that sad reality aside, respect goes out to Jennings and the other black candidates who ran for office so soon after voting rights were even allowed in the county.

A Black candidate for State Senate won over 80% of the Countywide vote in this County in 2022 over a White incumbent. Like most historically racist parts of the country, county voters nowadays seem to not care if a candidate is Black, just if the candidate has the desired party label.